THE CRIMINALIZATION OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY AND REWRITING OF HISTORY

By Robert J. Boyle

Introduction

The New York City Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association (PBA), among others, have called for an anti‑Beyoncé rally in response to her Super Bowl performance. During it, she and her back‑up dancers performed a song and moves that have been labeled as glorifying the Black Panther Party. In its literature the PBA has posted pictures of Black Panther Party/Black Liberation Army political prisoners including Herman Bell, who happens to be my client and who is appearing before the Parole Board in March 2016. Convicted of murdering two police officers in 1971, he has now been in jail for 43 years.

No one in the mainstream media has challenged the PBA’s characterization of the BPP. Nor has there been outrage over its call for a boycott of a mainstream artist for daring to favorably portray the BPP and its place in the Black liberation movement (if in fact, that’s what Beyoncé was trying to do). This is so because the true story of the destruction of the BPP and the government’s role in it has been suppressed. The BPP and the political prisoners from that organization have been successfully “criminalized”.

This article is an attempt to correct the record and tell part of that history. It is not an exhaustive history of the BPP itself, something that can and should only be told by BPP members. The law enforcement documents quoted and referenced were obtained from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and NYPD over a twenty‑year period in a federal civil rights lawsuit brought on behalf of Dhoruba Bin Wahad. Bin Wahad v. FBI, et al, 75 Civ. 6203 (USDC/SDNY) Bin‑Wahad is a former BPP political prisoner who was able to win his freedom in 1990 after proving – through the government’s own files – that he was the victim of a carefully orchestrated law enforcement frame‑up. The author was one of the attorneys in that case, along with Bob Bloom and the late Elizabeth Fink.

But this is not just a history lesson. Many other political prisoners from that period, including my client Herman Bell and his codefendant Jalil Muntaqim, remain in jail today. Many, especially the youth, do not know the history of the BPP, the government’s role in its destruction or even the existence of political prisoners.

The Black Panther Party And Cointelpro

In 1967, the Black Panther Party for Self Defense was founded in Oakland, California. Its goals, enumerated in its ten‑point program, were to achieve equality and self‑determination for Black people. Among other things, the Party called for community control of institutions within the Black community, such as schools and the police, an end to police brutality and murder and an end to the military draft for Black people. The BPP set up programs whereby its members fed breakfasts to school age children, opened free health clinics and demanded quality education. The Panthers also advocated the right to self‑defense, including armed self‑defense when under attack, even when that attack came from the police.

Within a year, there were approximately 21 chapters of the Black Panther Party with at least 500 members nationwide. In New York City, Black Panther Party offices opened at 2026 Seventh Avenue, New York, New York and 108A Fulton Street, Brooklyn, New York. There was also a Bronx and a Queens chapter.

The BPP’s militant advocacy for human rights and political empowerment alarmed the government, especially law enforcement. In 1967 then FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover had initiated a plan to “expose, disrupt, and otherwise neutralize” the activities of Black organizations, their members, and leaders and targeted the BPP as his primary scapegoat. The initiating document of this program known by the acronym COINTELPRO described the goals of the FBI:

“For maximum effectiveness of the Counterintelligence Program, and to prevent wasted effort, long‑range goals are being set.

1) Prevent the coalition of militant black nationalist groups. In unity there is strength; a truism that is no less valid for all its triteness. An effective coalition of black nationalist groups might be the first step toward a real “Mau Mau” in America, the beginning of a true black revolution.

2) Prevent the rise of a “messiah” who could unify, and electrify, the militant black nationalist movement. Malcolm X might have been such a “messiah;” he is the martyr of the movement today. Martin Luther King, Stokely Carmichael and Elijah Muhammad all aspire to this position. Elijah Muhammad is less of a threat because of his age. King could be a very real contender for this position should he abandon his supposed “obedience” to “white, liberal doctrines” (nonviolence) and embrace black nationalism. Carmichael has the necessary charisma to be a real threat in this way.

3) Prevent violence on the part of black nationalist groups…Through counterintelligence it should be possible to pinpoint potential troublemakers and neutralize them before they exercise their potential for violence.

4) Prevent militant black nationalist groups and leaders from gaining respectability, by discrediting them to three separate segments of the community. The goal of discrediting black nationalists must be handled tactically in three ways. You must discredit these groups and individuals to, first, the responsible Negro community. Second, they must be discredited to the white community, both the responsible community and to

“liberals” who have vestiges of sympathy for militant black nationalist simply because they are Negroes.

Third, those groups must be discredited in the eyes of Negro radicals, the followers of the movement. This last area requires entirely different tactics from the first two. Publicity about violent tendencies and radical statements merely enhances black nationalists to the last group; it adds “respectability” in a different way.

5) A final goal should be to prevent the long‑range growth of militant black nationalist organizations, especially among youth. Specific tactics to prevent these groups from converting young people must be developed” (A 1‑6).

Similar plans were instituted by local law enforcement. In 1966, the New York City Police Department commenced its own “investigation” of the Black Panther Party based solely on the Party’s First Amendment activities. For example, the NYPD targeted the BPP’s program for community control of schools in the African‑American community. Reporting on an August 25, 1966 meeting of community organizations, the NYPD’s Bureau of Special Services (“BSS”) submitted the following memorandum to the NYPD’s Chief Inspector:

The speakers were all in agreement that the schools in Harlem were inferior in curriculum and that the teachers had little regard for their students. They stated also that if this system is permitted to go on, the Negroes will continue to be lacking in education…Further details regarding this boycott on September 12, 1966 will follow in another report. There were 40 persons in attendance at this meeting which ended without incident.

The NYPD regularly communicated with police departments throughout the country, sharing information on the BPP, its members and protected First Amendment activities. On June 13, 1967, for example, Deputy Inspector William Knapp requested that the Colorado State Police provide him with all information on “Panther Publications” assuring Colorado that the request will be treated “with discretion” due to the “confidential nature” of the BPP investigation (A 202). In May 1967, the NYPD requested the “names pedigrees, photos and other relevant information” on the BPP maintained in the files of the Los Angeles Police Department (A 205).

By July 1968, it was the opinion of the NYPD that the Black Panther Party “has the potential for great trouble…it is requested…that all uniformed and detective commands forward any information on the [Black Panther Party] to the Bureau of Special Services.

The NYPD created “index cards” memorializing information on the protected activities of all BPP members, their associates, their families and their friends. In the Bin Wahad lawsuit the NYPD produced copies of over 30,000 index cards memorializing information on over 15,000 individuals and organizations.

By mid 1968, the FBI and NYPD were working to “neutralize” the BPP on a daily basis. On August 29, 1968 FBI Special Agent Henry Naehle reported on his meeting with a member of an NYPD “Special Unit” investigating the BPP. SA Naehle acknowledged that the FBI’s New York Field Office “has been working closely with BSS in exchanging information of mutual interest and to our mutual advantage.” The NYPD official noted that his unit is actually in “competition” with BSS but that given their goals, such competition is a “healthy thing”.

Documents produced in the Bin Wahad’ lawsuit show a pattern of mutual activity by the FBI and NYPD designed to destroy the Black Panther Party. For example, an FBI “Inspector’s Review” for the first quarter of 1969 shows that the NYPD, in conjunction with the FBI, had an “interview” and “arrest” program as part of their campaign to neutralize and disrupt the BPP. The NYPD advised the FBI that

these programs have severely hampered and disrupted the BPP, particularly in Brooklyn, New York, where, for a while, BPP operations were at a complete standstill and in fact have never recovered sufficiently to operate effectively.

A series of FBI documents reveal a joint FBI/NYPD plan to gather information on BPP members and their supporters in late 1968. During an unprovoked attack by off‑duty members of the NYPD on BPP members attending a court appearance in Brooklyn, the briefcase of BPP leader David Brothers was stolen by the NYPD and its contents photocopied and given to the FBI (A 11‑14). Rather than seeking to prosecute the police officers for this theft, the FBI ordered “a review of these names and telephone numbers [so that] appropriate action will be taken.” (A. 13).

That “appropriate action” included an effort to label Brothers and two other BPP leaders, Jorge Aponte and Robert Collier, as police informants. On December 12, 1968, the FBI’s New York Office proposed circulating flyers warning the community of the “DANGER” posed by Brothers, Collier and Aponte. The NYO proposed that the flyers “be left in restaurants where Negroes are known to frequent (Chock Full of Nuts, etc.)” BSS later told the FBI that its proposal was successful in that David Brothers had come under suspicion by the BPP. An FBI memorandum dated December 2, 1968 captioned “Counterintelligence Program” noted that “every effort is being made in the NYO to misdirect the operations of the BPP on a daily basis.”

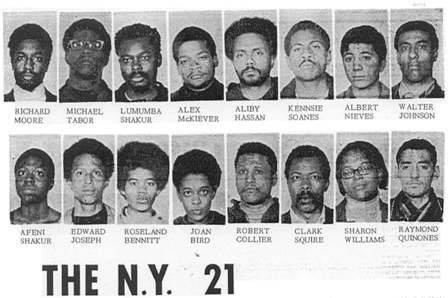

On April 2, 1969 21 members of the Black Panther Party were indicted and 13 were arrested in New York County on charges of conspiracy‑‑People v. Lumumba Shakur, the so‑called “Panther 21” case. An NYPD memorandum notes that the Panther 21 arrests were considered a “summation” of the overt and covert investigation commenced in 1966.

In a bi‑weekly report to FBI Headquarters listing several counterintelligence operations the FBI reported that

To date, the NYO has conducted over 500 interviews with BPP members and sympathizers. Additionally, arrests of BPP members have been made by Bureau Agents and the NYCPD. These interviews and arrests have helped disrupt and cripple the activities of the BPP in the NYC area. Every effort will be made to continue pressure on the BPP…

In the late 1960’s there was considerable support among white activists and some liberals for the BPP and its programs. When the Panthers came under attack committees were formed to aid in the legal and political defense of members. But these support efforts were often impeded by FBI/NYPD counterintelligence. For example, following a fund raiser at the home of conductor Leonard Bernstein, the FBI sent spurious letters to those in attendance in order to “thwart the aims and efforts of the BPP in their attempt to solicit money from socially prominent groups…” This included sending articles from the BPP newspaper to the primarily Jewish attendees of the gathering expressing the BPP’s support for Palestinian self‑ determination.

In July 1969, the NYPD sent officers to Oakland, California to monitor the Black Panther Party’s nationwide conference calling for community control of police departments. As reported by the NYPD, the BPP’s plan “the residents in each precinct would elect a Police Councilman who together with the other fourteen councilmen would elect a commissioner of police for the division. That commissioner “would define policies within its department…” An NYPD memorandum candidly acknowledged that community control of the police, “may not be in the interests of the department”

Ultimately, law enforcement’s most successful tactic was to create internal divisions within the Party itself. One example concerning Bin‑Wahad is illustrative. He was among the 21Panther arrested in April 1969 and held on $100,000 bail. By March of 1970, the BPP had raised enough money to post bail for the most articulate leaders and chose Bin Wahad for release. The FBI ordered that he be immediately and continuously surveilled and that donors of bail money be identified. Director Hoover reminded his New York Office that the activities of Panther 21 defendants were of “vital interest” to the “Seat of Government”.

For the next year Bin Wahad traveled extensively throughout the United States, speaking in support of the BPP and his incarcerated co‑defendants. These activities resulted in his becoming a major focus of COINTELPRO. Mr. Bin Wahad was placed on the FBI’s “Security Index”, “Agitator Index,” and in the so‑ called “Black Nationalist Photograph Album”.1

_______________________________

1 As discussed in the 1976 Congressional Report commonly known as the “Church Committee”, the “Security Index” and “Agitator Index” were lists of dissidents who would be incarcerated in the event of a “national emergency”.

_______________________________

A series of COINTELPRO operations shows how the NYPD assisted the FBI in a sophisticated effort to discredit Bin Wahad within the Black Panther Party. Through their warrantless wiretaps of BPP offices and residences, the FBI became aware in May 1970 of dissatisfaction among New York BPP members, including Bin Wahad, with West Coast BPP members. It was felt that West Coast members were wrongfully taking money raised for the Panther 21’s defense. A COINTELPRO operation prepared by the New Haven Field Office and submitted to the FBI’s New York Office consisted of a spurious note whereby Bin Wahad accused BPP leader Robert Bay of being an informant. This successful operation resulted in Bin Wahad’s demotion within the BPP. (A 78) Aware of Bin Wahad’s disillusionment, the FBI disseminated information regarding BPP strife to the media and participated in a plan to either recruit Bin Wahad as an informant or have BPP members believe he was an agent for the FBI.

In August 1970, BPP leader Huey P. Newton was released from prison. A plethora of counterintelligence actions followed which sought to make Newton suspicious of fellow BPP members, particularly those, like the Bin Wahad, who were on the East Coast.

By early 1971, the plan bore fruit. On January 28, 1971, FBI Director Hoover reported that Newton had become increasingly paranoid and had expelled several loyal BPP members:

Newton responds violently…The Bureau feels that this near hysterical reaction by the egotistical Newton is triggered by any criticism of his activities, policies or leadership qualities and some of this criticism undoubtedly is result of our counterintelligence projects now in operation.

COINTELPRO’s enormous success resulted in a split within the BPP with violent repercussions. In early January 1971, Fred Bennett, a BPP members affiliated with the New York chapter was shot and killed, allegedly by Newton supporters. Newton came to believe that Bin Wahad was plotting to kill him. Bin Wahad, in turn, was told by Connie Matthews, Newton’s secretary, that Newton was planning to have Bin Wahad and Panther 21 co‑ defendants Edward Joseph and Michael Tabor killed during Newton’s upcoming East Coast speaking tour. As a result of the split and in fear of his life, Mr. Bin Wahad, along with Tabor and Joseph, were forced to flee during the Panther 21 trial.

On May 13, 1971, the Panther 21 were acquitted of all charges in the less than one hour of jury deliberations which followed what was at that time the longest trial in New York City history. BSS Detective Edwin Cooper begrudgingly reported to defendant Michael Codd that the case “was not proven to the jury’s satisfaction”. Alarmed and embarrassed by the acquittal, J. Edgar Hoover ordered an “intensification” of the investigations of acquitted Panther 21 members with special emphasis on those who were fugitives (A 105).

“Newkill” and the Continuations of Cointelpro

On May 19, 1971, NYPD Officers Thomas Curry and Nicholas Binetti were shot on Riverside Drive in Manhattan. Two nights later, two other officers, Waverly Jones and Joseph Piagentini, were shot and killed in Harlem. In separate communiques delivered to the media, the Black Liberation Army claimed responsibility for both attacks. Immediately after these shootings, the FBI made the investigation of these incidents, which they called “Newkill,” part of their long‑standing program against the BPP conducted by their “Racial Matters” squad, and set up a liaison with the NYPD.

Before any evidence had been collected, BPP members, in particular those acquitted in the Panther 21 case, were targeted as suspects. Hoover instructed the New York Office to consider possibility that both attacks may be result of revenge taken against NYC police by the Black Panther Party (BPP) as a result of its arrest of BPP members in April, 1969 [i.e. the Panther 21 case] (A108).

On May 26, 1971, J. Edgar Hoover met with then President Richard Nixon who told Hoover that he wanted to make sure that the FBI did not “pull any punches in going all out in gathering information…on the situation in New York.” Hoover informed his subordinates that Nixon’s interest and the FBI’s involvement were to be kept strictly confidential.

“Newkill” was a joint FBI/NYPD operation involving total cooperation and sharing of information. The FBI made all its facilities and resources, including its laboratory, available to the NYPD. Defendant Michael Codd, then NYPD Chief Inspector, was assured of “complete” FBI cooperation. In turn, NYPD Chief of Detectives Albert Seedman, who coordinated the NYPD’s investigation, ordered his subordinates to give the FBI “all available information developed to date, as well as in future investigations”. The FBI and NYPD held regular conferences during which all parties were fully briefed.

By mid‑1971, many BPP members, particularly those from the East Coast, were “underground”. Some went underground to flee FBI‑instigated factional violence or further government attacks. Other chose to go underground to be part of the Black Liberation Army. Over the next 4‑5 years numerous BPP and/or BLA members were arrested and/or shot dead during streets confrontations with the police. The latter include Twymon Meyers, Anthony Kimu White, Harold Russel and Zayd Malik Shakur. The former include Bin‑Wahad, Herman Bell, Assata Shakur, Jalil Muntaqim and Robert Seth Hayes. Those arrested were charged with various offenses including the deaths of police officers killed in actions claimed by the Black Liberation Army. Their trials were often a mockery of justice: evidence was fabricated and exculpatory evidence suppressed. Bin Wahad was convicted after three trials and served 19 years before being able to prove that he was the victim of a frame‑up. Others have not been as “fortunate”. Herman Bell and Jalil Muntaqim were able to obtain evidence of egregious prosecutorial misconduct. But the courts denied their efforts at winning new trials and they remain in jail today. Both have appeared before the Parole Board six times. Each time they have been denied due to the “seriousness of the offense”. And each time they appear, the NYPBA submits, through its website, tens of thousands of form letters urging that they never be released.

Herman Bell appears again before the Parole Board in March 2016. Jalil Muntaqim and Seth Hayes appear in July 2016. Each has now spent more than 40 years behind bars.

________________________________________

Robert J. Boyle is an attorney in New York City who has represented many BPP/BLA political prisoners including Dhoruba Bin Wahad (freed in 1990), Marshall Eddie Conway (freed in 2014) and Herman Bell, who appears before the NYS Parole Board in March 20, 2016.

Reblogged this on Pauliebronx's Blog.