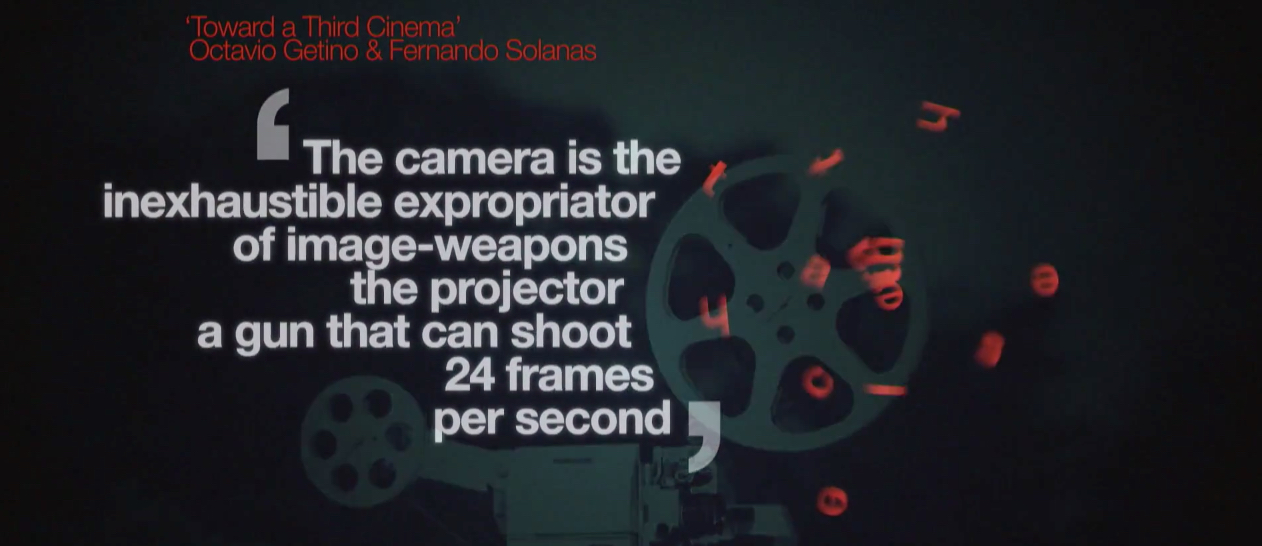

I and some others were asked recently by Dhoruba bin-Wahad to consider the story (below) from Al Jazeera’s The Listening Post at the end of 2017 called “History through Cuban Eyes: Noticiero ICAIC.” Specifically, we were being asked by bin-Wahad to produce stories and more discussion around the politics of art, media and popular culture based on the perspective shared of those fields in this story about Cuba’s post-revolution media work and the politics therein. The Cuban news and media-makers in the post-revolutionary period understood that no movement could have been initiated nor sustained without an aggressive clarity around the role image plays. For them cinema was “seen as most provocative method for education of the masses” and the newsreels created for movie theaters to play before features would become the part of the anti-colonial, anti-imperial defense against United States empire. Culture was seen as a battleground, they worked to “transform news into art…” and were clear that “the camera is an inexhaustible expropriator of image-weapons, the projector a gun that can shoot 24 frames per second.”

This has been the crux of my professional and activist work for some time, the intersection between politics and media, or better yet, the political economy of mass media, or better still, the imperial and/or colonizing function media are set to play by those who understand them, properly, as weaponry in service of ideological, geopolitical or imperial conquest. These and related issues have also been battlegrounds and the source of many disagreements as, I have found, the struggle to understand the function of celebrity, popular culture or the establishment of whole environments meant specifically to manage public opinion, construct consciousness and set patterns of behavior has been an uphill one where even the best and brightest find it difficult to accept the inextricable ties existing between mass media/communication, popularity and power.

I watched the Al-Jazeera story and its recounting of a Cuban perspective in defense of their 1959 revolution and the role news, art and popular culture were clearly meant to play and thought of the many battles we’ve engaged here at iMWiL!. For instance, I Mix What I Like: A Mixtape Manifesto was my attempt to argue that many in hip-hop and media studies (and related social movements) had not appropriately considered the political context in which all this culture, art and media were/are being produced and as such falsely attached (confused) concepts of “progress” with celebrity. In fact, my primary argument then (and now) was that the pre-existing reality of a colonial relationship held between African America and the United States broadly speaking demands a media environment which acts in service of said colonizing mission meaning that anti-Black depictions of people and related histories would, of political necessity, be as prevalent as copious studies continue to show them to be. Hip-hop, as it were, would not, therefore, be extinguished as a product of a colonized community, but rather, as Frantz Fanon said, be “fixed in a colonial form” and used to “testify against” its progenitors. And as I, and others, argued for some time, efforts at “media reform” that did not first take into account the need to assume political power were the conclusions reached by an all too-White and liberal set of analyses.

I was arguing then (2011) for a deeper appreciation of the history and contemporary potential value of the rap music mixtape as an alternative communicative network which needed to be further developed as part of a fully revolutionary alternative public sphere and argued that, “No serious study of the politics of media can conclude that new technology will upset existing social relationships, and it appears again that advancing study of the Internet bears that out.”

This was a difficult argument to make in the face of both a euphoria around the Internet and social media and the untenable belief that all this was “leveling” the journalistic or representative “playing field.” For one example, in 2012 my attempt to emphasize the then comments of Secretary of State Hillary Clinton that she intended to use hip-hop as jazz had been used in the 1950s to rebrand the U.S. as less hostile to world majority populations was not necessarily well-received and seemed persistently misunderstood as something that individual artists could overcome.

Or more recently, I attempted once more to challenge the constructed and severely flawed narrative in hip-hop (music, journalism, etc.) around the challenges waged in the 1990s by C. Delores Tucker and argued that this confusion stems largely from our own lack of ideological clarity and also that her fight smashed head-on against an internally-led defense of hip-hop’s rising popularity and commercial success, largely in part due to a persistent and profound misunderstanding of the value, origin or political nature of fame or “success.” The point being, again, that a continuing misreading of the relationship between popularity and politics (or failing to understand that in this political context all that is popular is a fraudulent representation of whatever it claims to be) hampers our ability to properly chart the distance between fame and freedom and makes more difficult the clarification of what Kwame Ture has been offering as a warning since 1966, that, “Black visibility is not Black Power.”

Today the struggle to make arguments challenging an automatic assumption that the Internet helps us all is even more difficult. Even the resurgence of attacks on Net Neutrality haven’t fully awakened many, who have been given no prior training or encouragement to understand the (military) history of the Internet or the role media and popular culture play in governance, continue to assume that equality is just around the corner largely because we can all post, like and comment. There is an intensely propagandized belief that the Internet does upset conventional paths to popularity and allows individuals to circumvent organized (commercial, corporate, colonial) power. It is timely then that this story about Cuban revolutionary application of media be considered and debates waged again around the value of commercial “success,” popularity or amounts of “followers.”

There are those who continue to add depth or much important updating to this particular critique, not the least of which is Safiya Umoja Noble who writes in her new book (an instant classic I think) Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism, that rather than bringing change to existing social relationships new media technology, specifically, “the power of algorithms in the age of neoliberalism… reinforce oppressive social relationships and enact new modes of racial profiling, which I have termed technological redlining” (emphasis added). One lesson we can glean from her work, or at minimum one question we can raise, is in what precise ways are we claiming advance, progress or victory when so much of what activists consider the basis for such a determination is popularity via an Internet that, as Umoja Noble argues, uses “algorithmic oppression” and “artificial intelligence” toward the purpose of “the commercial co-optation of Black identities, experiences, and communities [by] the largest and most powerful technology companies…” She concludes that, “We need all the voices to come to the fore and impact public policy on the most unregulated social experiment of our times: the Internet.”

I agree. Because if they were correct, and the Cubans were, that cinema is a powerful social manipulator and the camera (media tools) a weapon in a war for liberation then certainly the Internet is the most elite, tactical “smart bomb” ever created, meant to deliver upon those in power what they always want, “full spectrum dominance” and is making harder our efforts at popularizing a critical, resistant mass consciousness. In fact, Umoja Nobles’ concerns over “commercial co-optation” speak frighteningly well to the warnings raised by the Cuban revolutionary example. For if, as she warns, we risk in this Internet age having Black experience, identity and suffering co-opted by media companies serving a colonial function, that is, one of theft of land, labor and culture, then the media, news-making purpose spoken to historically by these Cuban revolutionary media-makers is one we absolutely best make our own because, as they said, “… a country [or people] that loses its audiovisual patrimony is losing its own history.”

Wow! What a find. This brings to mind a couple of images. One, the movie Tangerine, which shows what you can do with an iPhone, an app, a steadycam rig, and some clamp-on lenses. And two, the power of words to evoke images. I thought of Supcomandante Marcos and the Zapatistas who in 1994 declared war on Mexico with a series of very descriptive –oh what did he call them–“Comunicados de la Selva Lacandona”.