It’s September 1966, and the regular reader of Ebony gets the sinking feeling that its jali, Lerone Bennett Jr., is a little disconcerted. In the article, the magazine editor and history book author is in a vehicle zooming along in South Carolina at 70 mph by Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee chairman Stokely Carmichael, and a group of white racists are trying to run them off the road. The shirtless Carmichael, along other SNCC organizers and Bennett, are on their way to Lowndes County, Alabama, where SNCC is forming the first Black Panther Party. The Black men confront the white men, and the crackers jumble and crumble.

The opening scene of Bennett’s story is powerful and macho. There’s a New Black Man, the historian is declaring, so don’t confuse him with Alain Locke’s New Negro. That run-in they just had? It was “part of a day’s work. Something that needed to be done had been done. A man had challenged a man—and a man answered.”

Bennett introduced his readers to the real Stokely Carmichael—a man who “walks like Sidney Poitier, talks like Harry Belafonte and thinks like the post-Muslim Malcolm X.” So what was this “Black Power” of which white people are so scared? It meant manhood and non-nonviolence. It meant trying to build up the power bases Black people had during Reconstruction. Bennett quoted Carmichael: “It is a way for them to come together to stop oppression by any means necessary… I have always believed that Black people had to stand up and take the things that belong to them.” Right On! Bennett had scored another success. He was able to explain to millions of Black Americans what Black Power meant outside the white mainstream media hysteria over the term and its popular proponent. Very few Black writers had the time and resources that Bennett, who had been Ebony’s associate editor since 1954, had to give a full portrait of SNCC and Black Power.

The Carmichael profile did not make the cover (that was reserved for Black television pioneer Bill Cosby, his wife Camille and daughter Erika, high-flying in the I Spy days), but it did lead the magazine’s feature section. Its positioning shows the schizophrenia that lay ahead for Ebony, a Black lifestyle magazine that the Movement was going to force into 360 degrees of Blackness. By this time, Jet already had the reputation of being at seemingly every point of action in the Civil Rights Movement, and now it was Ebony’s turn. Ebony/Jet publisher John H. Johnson had sensed history’s wind; he had revived his Black intellectual magazine, Negro Digest, in 1961, the same year Black Communists and other Black activists in New York City created a quarterly “little magazine,” Freedomways. But it was Bennett and Ebony that was now going to lead the power parade, Bennett from the corporate inside, Bennett with his very-close-to-decolonizing written words.

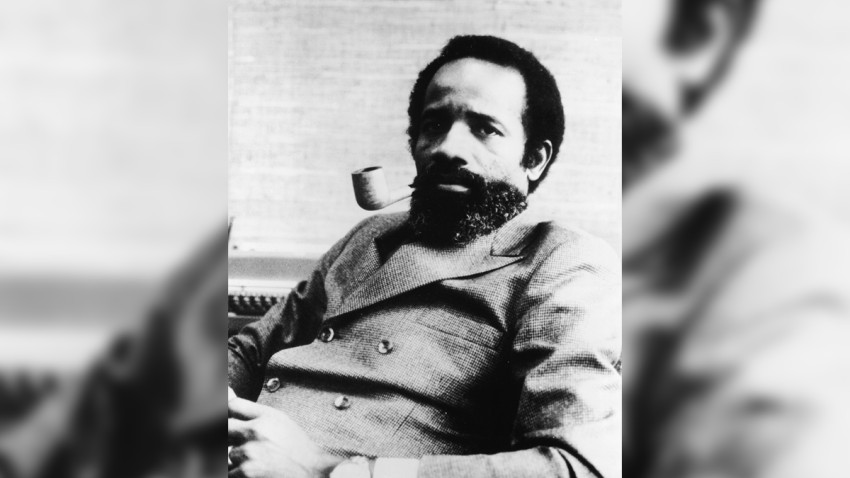

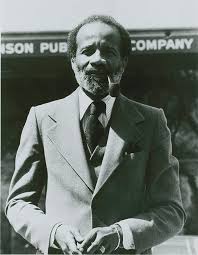

The social historian was rising in ways few outside of the Black community understood. By this time, he had written a biography of Martin Luther King called What Manner of Man, and his Black American history book, Before The Mayflower, was becoming a standard text for Black teachers and Black librarians who wanted an alternative to the “objective” Black historian John Hope Franklin. By the time of the Carmichael profile, John Henrik Clarke, an associate editor of Freedomways, had written an entire article in the periodical praising him. He was not in the white mainstream—not one of the Black writers that elite whites had chosen to define the Black experience for them. So although he was a contemporary of James Baldwin, Alex Haley, and Gordon Parks—the holy trinity of mid-1960s top Black nonfiction writers—he was largely invisible to white mainstream eyes. Bennett was then what we in the third decade of the 21st century would refer to as “Black famous.”

But Baldwin, as always, understood the moment and the stakes and could articulate exactly what Bennett would in one of his books call The Negro Mood. In the 1960s, Baldwin was asked by a television reporter if he would ever write anything that didn’t have a message. His answer held in the air until it was seized by the Zeitgeist: “I don’t quite know what that means. In my view, no writer who ever lived could have written a line without a message, you know. It depends on—what you’re asking me, I think, is to what extent do I intend to become a polemicist or a propagandist. Well, I can’t answer that because the nature of our situation has imposed on everybody involved in it things that one wouldn’t ordinary do; you take risks that you wouldn’t ordinarily take. I don’t think of myself as public speaker or a civil rights leader or any of that, but I’m not about to sit in some tower somewhere cultivating my talent.”

So Bennett, out of his comfortable South Michigan Avenue tower in the Second City, placed himself in the thick of the Black Power movement, literally on the frontlines. The historian witnessing in the center of the century, in the inner circle of radical Black struggle. He was ready to take those risks, hydrating himself with Black Power and Pan-Africanism. His boss, publisher Johnson, was also willing to risk some controversy—but only if he could financially profit from it. The man who had pioneered the post-World War II “Negro Buying Power” consumer market (critiqued by this article’s publisher, Dr. Jared Ball of Morgan State University, in his forthcoming monograph The Myth and Propaganda of Black Buying Power) was always ready for more money; if Black Power content drove increased Black disposable income to him, Solid!

In the article, Bennett said Carmichael “is not playing; he is going for broke.” He wasn’t the only one. From 1966 until what Gil Scott-Heron would call “defenders of the dollar eagle” would step in during 1976, Bennett and a small band of Johnson publication staff would hold the line and intellectually propel themselves forward in the exact way Eldridge Cleaver described the purpose of writing: to throw a spear in the heart of white America. For a moment, Bennett was Black America’s premier popular historian, the man passing out nourishing dark nectar to millions of Black readers. Black Power and Black history had merged within his being, and he found out he had more freedom and reach than most of his academic peers who were busy creating the discipline of Africana Studies during this ten-year period. But he was ultimately slowly, slyly thwarted not by white supremacist historians, but by the consequences of being the company man he always was.

Bennett was the as-told-to author of Succeeding Against The Odds, the 1989 only-in-America memoir of his boss, John H. Johnson. The boss had taken a $500 loan against his mother’s furniture and gambled that Negroes wanted their version of Reader’s Digest (Negro Digest), Life magazine (Ebony) and Quick (Jet). He won, and big. But Johnson was always clear on what the game was about, as he said through his star employee. “I survived TV and the age of the photograph, and historians have been kind enough to say that I invented a new journalism that made it possible for Black media to weather the storms of change. This is a flattering assessment, but I wasn’t trying to make history—I was trying to make money.”

And by 1966, he had found the secret to making lots of it: embracing Black Power as much as he could. He had seen the success he had when Emmett Till’s mutilated face was published in Jet in 1955. It was a new day; no longer did Johnson have to worry about his racist white printers, as he did in Ebony’s infancy. His Johnson Publishing Company Book Division had already been ahead of the curve with the publication of Mayflower, a history book that came out of an Ebony series. In 1965, the magazine had correctly called racism correctly a white person’s problem. Negro Digest had been renamed Black World. All Johnson had to do now was continue to keep ahead of the herd, making sure that any raised fist had ready cash in it. Key to this was Bennett’s free editorial hand.

Unlike his boss, Bennett was trying to make—as in write—history. “In terms of living Black history, he perhaps adopted a style of history pioneered by (W.E.B.) Du Bois’s Souls of Black Folk,” wrote Christopher Tinson in his substantive journal article on Bennett. “[H]e sought to forge a reparative, justice-centric, visionary account of past human endeavor and the stakes of social disequilibrium.”

Bennett understood that he was in the locus of the Black century—center stage, between hundreds of years of Negro toil and a new African-American and Pan-African future—and wrote thusly.

Tinson explained how Bennett operated in Ebony, and how it benefited both him and his boss. “Bennett’s approach to publishing was methodical and systematic. Lectures and speeches became articles, articles became books, or anthologies…. Bennett had the best of both worlds in terms of institutional credibility among all sectors of the Black community. Bennett’s work ethic and standards of excellence had earned the trust of John H. Johnson. The two carved out what was an enviable relationship. Bennett had access to the publishing mogul, and Johnson needed Bennett’s intellectual heft to bolster the magazine’s reputation and commitment to sincere and earnest coverage of Black life beyond the simple demands of capitalist advertising and an aspiring Black middle class’s dogged pursuit of the high life.

“But Johnson was no fool,” continued Tinson. “And although he refused to wear his politics on his sleeve, Bennett viewed Johnson as a sincere and chief advocate of Black life. Effectively, Bennett was the bridge between across a rather full spectrum that stretched from petty capitalist, Black bourgeoisie, churchgoing, assimilationist community, to grassroots militants and middle- and working-class intellectuals with nationalist proclivities, to full expressions of Black elite aspiration. No matter the segments of the Black community and their ideological shadings or capitalist accouterments, in Bennett’s view, their fates were linked, and moreover, they all had to answer the call of history and the demand of time.”

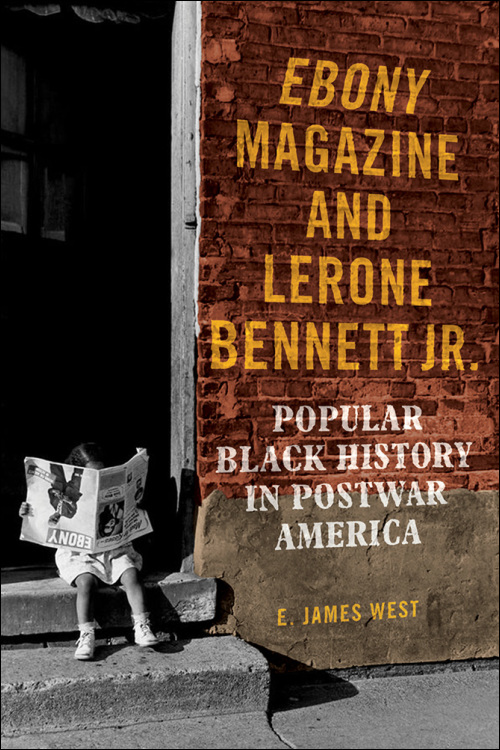

Time and history have finally caught up to Bennett, and in a considerable way. In a fantastic, deeply-contextualized new book about Ebony and Bennett, Ebony Magazine and Lerone Bennett Jr.: Popular Black History in Postwar America (University of Illinois Press), released this February, E. James West documented the Black Power-era Johnson Publications (Hoyt Fuller, the editor of Black World; Bennett, Allan Morrison, Alex Poinsett, Hans Massaquoi, longtime international editor Era Bell Thompson and relatively new staffer A. Peter Bailey, a former aide to Malcolm X) and how they reflected the times. Briefly, major Black radical scholars wrote for the magazine. Ebony was large in those days—13 ¾ by 9 ¾—and now it would also have matching depth. Wrote West: “The result was unquestionably a high point of Ebony’s engagement with Black Power and Black political, cultural and historical militancy.”

In 1968, Bennett was comfortable enough at Ebony to take on a heretofore sacred subject: “Was Abraham Lincoln a White Supremacist?” In that new Ebony/Jet/Black World the writers and editors made, Black thought would have no limitations.

“Bennett was a catalytic figure for Black/Africana Studies, and an early architect,” wrote Tinson. “Coordinators and architects of Black scholarship all relied on the writing, speeches, and thinking of the Ebony editor. His reputation as a keen editor with his eyes and ears open to the directions of hundreds of local Black communities facilitated his crafted reputation as a trusted scholar. Each vocation reinforced the other such that the two were inseparable. In the role of journalist Bennett kept the pulse of protest and self-assertion, as a historian he could historicize where all the impulses of agitation first emerged.

“The roots of protest were as if not more important than the present-day outbreak of rebellion. Bennett regularly reminded readers and colleagues that the protests and demands and unrest of the 1960s and 70s did not emerge absent history. If one wanted to know why Watts happened or Harlem or Detroit, all they needed to do was read the history of Black life in those cities decades before the tumultuous 1960s.”

Because of Ebony’s tremendous reach, the magazine was essentially in charge of popular Black history for the masses in the 1950s and 1960s. But the Black Power that Ebony became an unapologetic proponent of started to manifest itself in Black America. What had been building up for a long time in America seemed to explode between 1968 and 1970. Martin Luther King’s 1968 assassination, and the rebellions in American cities that happened before and after it, opened all the doors that were available. Behind those doors were new opportunities to produce, among other things, Black history products. Across the nation, newly desegregated Black college students began demanding, and got, their white colleges to create Africana Studies (or Black Studies, as it was originally called). Documentaries about Black life began airing on commercial television and a new forum, public television. Public affairs programs were created on both television systems to discuss Black news, history, and culture. Music radio that had served Black communities since the 1950s became more militant, with Black deejays and brand-new Black newscasters taking a more engaged role in educating and socializing their communities.

Ebony took advantage of the situation it had helped create. It began to market Johnson Publications as the source for Black history, and produced new products, like the multi-volume Ebony Pictorial History of Black America, to affirm its leadership with its core audience. And, at least initially, Black World was the leading Black intellectual magazine in America.

In the early 1970s, Bennett and other Black scholars wanted to create Black institutions that would be de-colonized: The Institute of Black World, Black Academy of Arts and Letters, the Black Scholar journal. But it was hard to be decolonized in a newly-desegregated America. Black Power would last as long as the Black Power organizations—the Black Panthers, SNCC, the Congress of Racial Equality—that were under constant attack survived. When they faded, the land grew slowly quiet, with only the movements for Black electoral politics attempting to fill the socio-political void.

Bennett covered the sixth Pan-African Congress in Dar Salaam, Tanzania for Ebony in 1974. Covered it and spoke there. The magazine had a picture of the historian addressing the assemblage in its photomontage. He wrote a serious, analytical piece in which he admitted to the reader that he was unsure if he was seeing Pan-Africanism’s birth or death. “It was caucusing, debating, going through the painful process of adapting the Pan-African dream to the Pan-African reality.” At that meeting, he documents the painful deletion of the word “movement” from Pan-Africanism in all the Congress’ official documents. After discussing the disappointment of the African American delegates—led by Dr. James Turner of Cornell University and unapologetically part of the defeated progressive wing wanting a Pan-African movement—he finished: “If that was not the beginning of the ending of the Pan-African Crusade, it was at least the ending of the beginning of a painful process of reeducation which may yet make the reality match the splendor of the dream.”

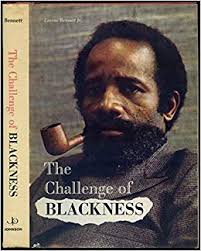

The following year, Bennett’s “The Making of Black America” Ebony history series was revised and published in book form as The Shaping of Black America. This very-underrated history survey would solidify that there was indeed a Black America—a nation within a nation. Bennett named Black America’s founders: Richard Allen, Paul Cuffe, David Walker, the founders of Freedom’s Journal, the first Black newspaper, and others. He discussed in detail the Black convention movement where Black leaders would fight for how the struggle would be defined. Bennett was once again attempting to show that what we always had done we were doing—testing the various and new cultural, political and social directions.

But most of Black America’s directions now pointed to only to the stars and stripes. Dreams of Black rebellion creating Black revolution for a Black reality were fading fast. The February 1976 issue of Ebony contained an Alex Poinsett where-are-they-now piece featuring now-less-visible Black radicals. As West points out, a month after “Ebony’s obituary for the Black revolution” saw print, Black World was cancelled. (Johnson said the circulation had dropped from 100,000 to its peak to 15,000.) Pan-Africanism began to fade into the intellectual background, and Black nationalism morphed from the dangerous political to the acceptable, harmless cultural.

The internal nation was being reborn in the 1970s, midwifed more by Madison and Pennsylvania avenues than Ebony’s South Michigan Avenue. “Soul” music on the radio moved to TV and began more and more to reflect Black victory. Soon, Corporate America eventually smoothed it out to a more desegregated, danceable beat. Negro History Week was upgraded to Black History Month in 1976 had become accepted in America, thus beginning the ever-present public tension between Black heritage nostalgia and Black radical struggle, one epitomized in the 21st century by the style of the Smithsonian National Museum of African-American History and Culture.

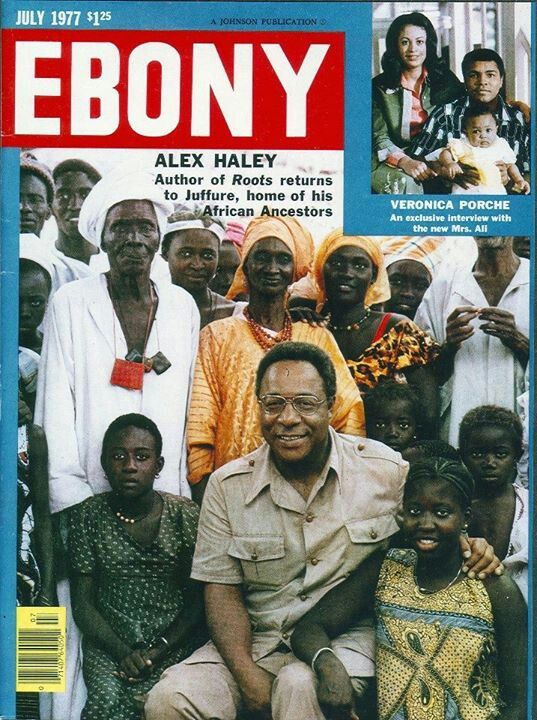

Into this new contradictory tension came storyteller Haley, who leaned hard into the heritage former after maxing out the radical latter a decade earlier with The Autobiography of Malcolm X. The ’60s was now officially yesterday—a dark-memory tunnel that led to the new day’s bright Afro-Sheen glow. By the time Roots aired on ABC in 1977, Bennett’s influence in Black America had been in many ways usurped. All Americans now had an alchemist narrator who could tell the history of Africa, the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, and the horrors of slavery in a way that was not only safe and comfortable to white audiences, but also compelling and cathartic. The fact that the show was a fantasy representation of a fantasy representation bothered few, even at Ebony. Crossover Black fame was in, and Haley was its North Star.

It is always challenging to explain and contextualize Haley, an intellectual and cultural chameleon. He sang America’s praises while writing the script of 1973’s Superfly T.N.T., a should-not-be-forgotten Blaxploitation flick in which Youngblood Priest, now out of the Life, assists African revolutionaries running arms to destroy a white-minority regime. Whether he knew it or not or knew but refused to say it out loud, Haley took the foundation made by Bennett and those Africana Studies scholars and professors who were determined to convince Black Americans that they were an African people. It was the beginning of the collective, somewhat media-fueled Pan-African conversion process that saw a peak in the 21st century forty years later with Marvel’s Black Panther, a Black History Month 2018 Hollywood film product about a Kunta Kinte figure who came home and became a Pan-African villain (!). By this time, Marvel and ABC were both owned by Disney, a conglomerate determined to be the master of the world’s imagination, one child at a time.

Haley’s book hit around the time of the Bicentennial, which was no accident. America was celebrating itself everywhere. Bennett had denounced the birthday, calling it “dangerous,” “astounding” and “frightening.” But Johnson was all for it.

Bennett’s de-colonized perspective about America’s celebration of itself was drowned out by the same capitalist forces that kept him alive in the first place. His enemies surrounded him at work—not in the form of Johnson Publications staff (many of whom had come or gone), but its consumerist philosophy and co-opting Black Heritage tourist ads that, according to West, “when published alongside Bennett’s historical treatises, such features often worked to blunt his militancy and to moderate the reception of his work on the part of Ebony’s readers.” Safe. Comfortable. Compelling and Cathartic.

Meanwhile, television had completely replaced print (and pushed radio in a far second place) as the primary conduit for Black history by the time James Earl Jones, the fantasy Haley, was in his fantasy Juffure in Roots: The Next Generations, the Roots sequel, merging African Holocaust history and American myth into a Horatio Alger victory witnessed by a worldwide audience: “You old African! I found you! Kunta Kinte! I found you, I found you!” But on many levels, the new master of crossover narration didn’t so much find the African past as much as pointed toward the Black market-culture future. Haley and ABC’s narrative was visually active, yet historically as smooth as the mass-media product Luther Vandross would soon croon early in the next decade. And Johnson ultimately sidelined Bennett in the best way possible—he eventually promoted him from associate editor to executive editor. Odds, the boss’s paean to American capitalism, would follow.

West emphasized the capitalist reality: “[E]ven at the height of Ebony’s engagement with Black Power during the late 1960s, the desire for Black critical perspectives emanating from many of its readers could only push back so far against its consumerist orientation and its dependence on corporate advertisers.”

Ebony refused to let Bennett go, so the now-legendary editor stayed at his post until he finally retired in 2005, the same year that John H. Johnson joined the Ancestors. (Angry that the magazine’s new leadership fired his daughter Joy in 2009, Bennett demanded his name and emeritus editor title be removed from its masthead.) Even at the turn of the new century, he maintained the same Black Power spirit, the serious anger. His 2000 book attacking Abraham Lincoln, Forced Into Glory: Abraham Lincoln’s White Dream, made him a pariah in mainstream historic circles, and the old man cherished the idea his rewrite and expansion of that 1968 Ebony article could still raise a fuss. Bennett’s fade was as slow as his rise: his extraordinary brain damaged by dementia, he once left his home in 2016 to wander and was reported missing. He was quickly found. But in truths found only beyond the surface it was clear he was doing what he had always done: searching to recover all we have knowingly or unknowingly abandoned.

Todd Steven Burroughs, Ph.D., is an independent researcher and writer based in Newark, N.J. He is the author of Warrior Princess: A People’s Biography of Ida B. Wells, and Marvel’s Black Panther: A Comic Book Biography, From Stan Lee to Ta-Nehisi Coates, both published by Diasporic Africa Press. His 2014 audiobook, Son-Shine On Cracked Sidewalks, deals with the first mayoral election of Ras Baraka, the son of the late activist and writer Amiri Baraka, in Newark. He is working on a journalistic, and, perhaps now, literary biography of Abu-Jamal.

No portion of this content may be reposted or republished in any part without the expressed written permission of the author or editor of imixwhatilike.org.

A good read thanks

THANK YOU, Kind Sir!

Great article. Lerone Bennett Jr was a large force on my early intellectual development. His books introduced me to black history. Ebony, on the other hand, had always seemed to focus on “black firsts” and persons successful in the workplace or in business. To me, it was the Cosby Show in printed form, noble but out of touch with reality for the majority of black folk. Wasn’t around when its pages were radical and challenged readers to see black reality for what it was, before it became a marketing tool for African-Americanism. Unfortunately, so few have been willing to unpack “black power” to recognize its fragility within the capitalist framework.

THANKS for your comment, Kwasi! West’s book starts a conversation African people should be having. At least we should be using Ebony/JET/Black World between 1966 and 1976, since Google has it all online.

Mr. Burroughs, what an enlightening article. For me it reveals that Lerone Bennett Jr. possessed an overpowering urge to tell a story, and having intimations of a unique story waiting to come out. A unique one anchored in his personal philosophy: “An educator in a system of oppression is either a revolutionary or an oppressor”!

THANKS! He clearly was the kind of historian who wanted us to feel the story!

Yes, an exceptional historian who expressed his muse in his own inimitable way.

Is it DrBalls fault that you lack melanin and can’t go with the flow! You need intellectuals to help grasp what is on deck! There is nothing difficult about this story. So you did a bid and spent time behind bars with us! If that’s your problem then so be it and now you want to immerse in our culture? Stay in your lane and keeps reading more than less!

This is the best article I’ve read in a long time. Very accurate in deconstructing the competing intellectual schools of thought at Ebony magazine.

The only omission is overlooking that Ebony based in Chicago, reflected a unique aspiration due to its large population of folks from Mississippi who would bring; down home ideas of family wealth, upward mobility and culture to “sweet home Chicago”.

Growing up a member of the Black Boule, Ebony/Jet magazine was required reading, as well as the photo essays by the Ebony staff were groundbreaking. Don’t forget, the Jet magazine “beauty of the week” was the first thimg you checked out while killing time at the neighborhood barber shop back in the days.

For many of us, John H. Johnson was a black media hero back in the early 1970s,

along with A.G. Gaston, Earl Graves, Percey Sutton and Haki Madhubuti (also from Chicago). Back then we felt that black radio, black magazines, black books and black music would be “our industry” that we could control. Black media ownership would create a new black progressive vanguard. We were wrong. But we had some great parties along the way….Gil Scott accurately called it Winter in America.

Keep up the good work.

THANKS for the GREAT comments, Brian! I’m sure West’s upcoming Bennett bio will fully reflect the Chicago you describe above.

And yep: everyone remembers The JET Beauty of the Week: It was the open-secret reason every guy loved JET. (Wasn’t she always on Page 43? 🙂 ). Growing up, JET was in EVERY Black-community liquor store, EVERYWHERE. Regardless of the critical tone my article above, Johnson is a media hero to me, too! Just hiring and keeping Bennett is more than most Black media entrepreneurs have done! For more on Black radio’s potential from the perspective you mention, please feel free to check this: https://drumsintheglobalvillage.com/2019/03/13/an-origin-story-of-gary-byrd-from-disc-journalist-to-world-african-griot/

Thanks for this very profound analysis and perspective.

THANKS, Charles!