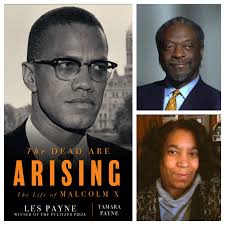

The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X.

Les Payne and Tamara Payne.

New York: Liverlight. 537 pp., $35.

Reviewed by Todd Steven Burroughs

It must be great to be a renowned-but-recently-deceased Black writer, because your half-effort gets a full heaping of praise from the grave. In this case, history is not rhyming, but looping. Again, a dead author who does not see his Malcolm X biography in print. Again, the literary/intellectual establishment beside themselves with advance praise to buttress any haters. Again, an incomplete work, by personal choice.

This time, the tragedy is not about fallacies in full biographical interpretation, innuendo, and research, a la Manning Marable. It’s about time itself: time that Payne, who worked as an investigative reporter, editor and columnist at Long Island Newsday until 2008, did not take to do this admittedly smaller book right before he joined the Realm of the Ancestors, leaving his daughter Tamara, his book’s chief assistant, the responsibility of bringing it to the finish line. So what could have been a sturdy, thematically-full biography of Malcolm X through the eyes of his siblings and, one assumes later on, his wife and children, becomes yet another Black nationalist narrative dream deferred.

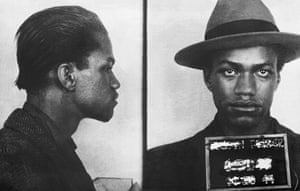

There are many, many lines that are beautiful (“He was like an accident about to explode,” the Paynes write of Detroit Red), but the narrative gaps are wide. With one or two notable exceptions, along with the inevitable pushing of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, as told to Alex Haley further into the realm of fiction, the father and daughter provide little more than extended and detailed family captions for the books yet to come. This disappointment is not (just) a tale of journalistic hubris as a substitute for historical work but of professional/personal priority.

What is so damn hard about producing a biography on Malcolm X? Biography is admittedly difficult, because it is, for the most part, a serious piece of scholarship wrapped in a popular form, created for a popular audience. Biography requires the meticulousness of a historian but the writing craft of a poet. Somehow along the way of this 28-year biographical journey, Payne made a purposeful choice to only use the latter and as much as possible to great effect, as it can be seen in the book’s open: “The metallic clicking of hoofbeats on the gravel road drew five-year-old Wilfred [Little] to the small-pane window…”

This writer sees three reasons that Malcolm X the biographical subject cannot be hurdled. First, is that his self-constructed myth, more than 50 years later, is so archetypally attractive to his core audience of the decolonized of every age, race and creed. Malcolm’s constituency, then, now and forever, wants to believe their leader when he claims that, for example, his Garveyite father was killed by the Ku Klux Klan. So when Payne uses his not-at-all overrated investigative skills to find out that it was way more probable, and substantiated by the record, that Earl Little died by accidentally falling while he was running to catch a train, it rips a key chapter or two out of the Black Radical Bible nested inside the decolonized mind. Hearing that young Malcolm stole money intended for his mother, to use another example, is both humanizing and a tad bit deflating. Second, that the decolonized nature of the subject, particularly in the revolutionary latter third of his life where he sets the stage for the Black Panther Party and the rest of the Black Power Movement, is not a favorite of white liberals, the notable funders, producers and audience of these kind of works. Third, that it would take a lot of time—and perhaps years of legal maneuvering—to get to the various kinds of archives needed for a thoughtful MX bio of any kind. Did Payne want to convince Minister Louis Farrakhan to open the Nation of Islam archives? Seemingly not. Did he want to sue the NYPD for its COINTEL-PRO files? It doesn’t appear so. Did the legendary journalistic digger want to dig into all those NOI/OAAU oral histories scattered everywhere? Not necessarily. Did he want to go overseas with translators and walk himself through Malcolm’s trip to Mecca and then through Africa, looking for documents? Guess not. Did he even want to check Marable’s sources on his most interesting and correct tidbits, so he could use things that strengthened his work? No mas. His daughter’s introduction is not only absent these conversations but even these thoughts. So the result is a truncated, grounded book about an internationalist, his Halfrican story half-told.

The Malcolm hobbyist Payne had the intestinal fortitude to shake Malcolm’s image (and to helpfully explain that Malcolm’s friend “Shorty” was actually three people), but, sadly, he lacked the heart and testicular grit to make a sustained effort to do the heavy lifting past dissecting the Lansing family album. (And it’s clear the family research was done mostly by internationally recognized Malcolm expert Paul Lee, who Payne hired as part of his research team.) Questions abound in the text margins. Why couldn’t/didn’t Payne interview Malcolm X’s nuclear family for this book, so he could keep and expand on the book’s established-and-then-abandoned Malcolm X Family theme? Why did he spend at least a decade not interviewing anyone? (The 52-member interview subject list, for the most part, stops in the late 1990s and, with one or two exceptions, doesn’t pick up again until 2015.) Why does most of the significant research stop on-third in? Why couldn’t Payne, a Pulitzer Prize winner, just call up fellow Newsday legend alum Robert Caro (someone who, a literary lifetime ago, sold his only house to make sure his first biography, of the racist, master builder of New York City Robert Moses, was done right) and ask how to get a grant for at least one $30,000 researcher, a par-for-the-course tactic for hundreds of white writers of Payne’s stature (and much less) over the last 30 years? Why, as a result of all of this apparent nonaction, produce and publish something now so beautifully written but, in the end, so historically insufficient and thematically incomplete? And why can’t these dying Boomer-era writers, who are far from impoverished and who could never be accused of harboring inferiority complexes, ever ask their agents and publishers on their deathbeds for a co-writer of equal stature who could do take the time to do this right, no matter how long it takes? (After all, who needs solo or top billing and a full royalty check from the grave?) Why, why, why?

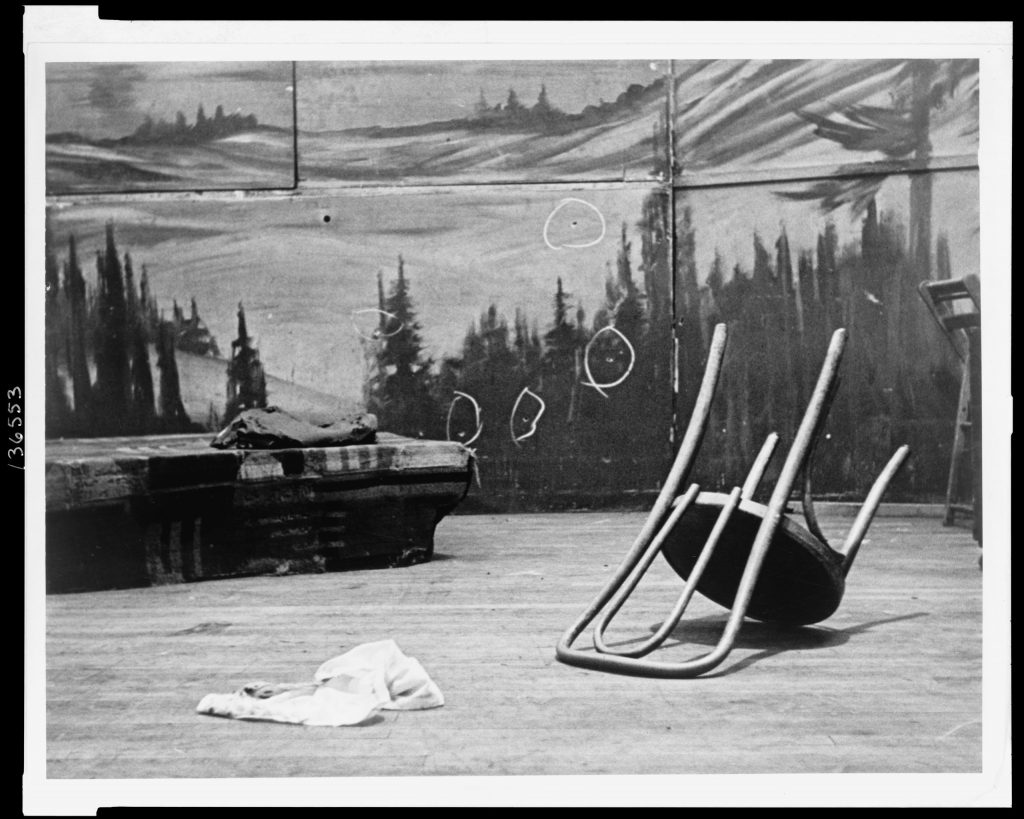

The author almost redeems himself with two interesting constructions: the secret meeting Malcolm had with the Ku Klux Klan and the final chapter, an insider’s view of Newark mosque the day of Malcolm’s assassination. If only the first were as significant as Payne makes it, but it’s in the part of the book where he almost falls into Smithsonian magazine/Michael-Eric-Dyson-“bio-criticism”-essay territory because he’s run out of intellectual, research-detailed, linear, scholarly steam. His recreations about Malcolm in Connecticut should have been, and would have made, nice third-person epilogues to a fuller, more seriously grounded work. But so much of this book is well-crafted filler between the well-researched-and-written Little family beginning and the well-written revolutionary ending. The superbly talented legend-who-earned-the-title uses his mojo for all he can because it’s all he has to give.

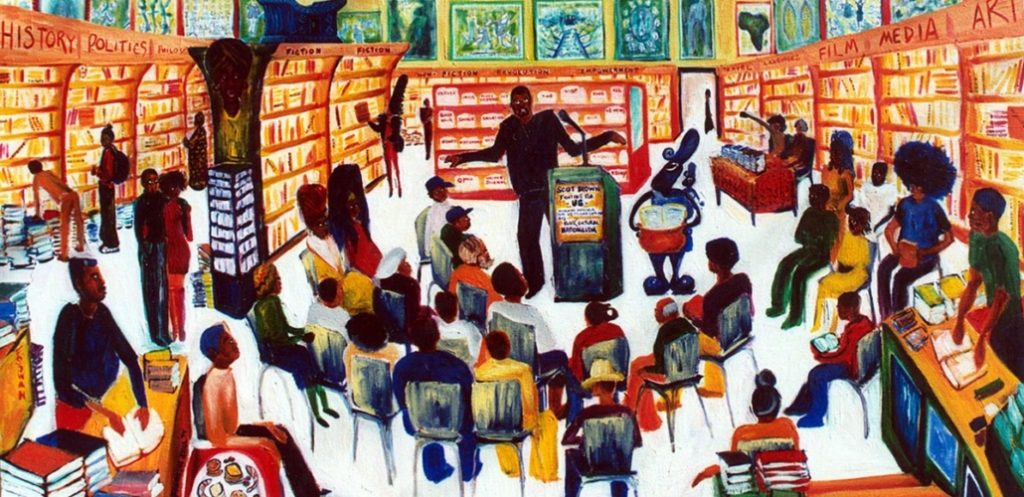

An obvious question is this, which in itself contains a message from the grassroots: There’s a lot a y’all writers and Africana scholars and stuff, and y’all been around a while. In fact, I grew up hearing y’all lay it down to the people. Whassup? Why can’t ya’ll fix this for yo’ boy? It is tragic that the answer is not complicated. Why can’t the dashiki-clad Africana Studies lovers of Malcolm X—particularly the oldheads that either knew him, were at least contemporaries, or were inspired by his live example as young people—produce a classic or at least serviceable biography instead of yet another conference?

The most simple, and hopefully not too reductive, answer is that it’s easier to talk than to write, particularly now in the Zoom era. (For the last eight months, Black America has had a “national” or “international” conference of one sort or another on average three days a week because now there’s no need for a hall or catering.) A more difficult answer is, frankly, that those O.G. Africana folks get paid to talk, also known as teaching. They pay their mortgages by talking about what they have read, dealing with students and their grades, doing paperwork, and providing other services to their institutions. So why do so many seem to visit the African continent more than the primary-source section of a major library? Because they get paid to do so, or because that’s their priority—so they can go can talk over there, and then come back home and talk here about how they talked over there. They don’t get paid to write books. Writing books is a job requirement to keep the ankhs polished or it’s a hobby, but for the Africana wing of Africana Studies—the New Afrikan Race Men and Women who openly proclaim their love of John Henrik Clarke, Charshee McIntyre, et. al.—it’s more of a choice. So, for the most part, with no real institutional support to do anything else, they choose to yak and maybe publish one book in their professional lifetime if they can. In 2020, YouTube University and now Zoom doubles as both their personal archive and the Afrikan World public university of their dreams.

So when someone has/gets a job in Africana Studies, you have to look at the lay of the land around him or her. Why did that person get hired? Who hired him or her and for what reason? Whatever the reason was, for the majority of them at the majority of American colleges it was not to take institutional time and research funds to thoroughly research Black radicalism—unless it’s presented in the most innocuous, ahistorical ways (*cough* Peniel Joseph’s whole career—pardon, must be COVID settling in

The writing discipline of W.E.B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, et. al. is lost on these modern showmen and show-women and many of their post-modern proteges, so, in conclusion, they can’t be trusted with researching and writing about a world-historical figure they say they love the most. Tired and tied from years of bureaucratic battles at institutionally racist (PWI) or indifferent (HBCU) spaces and constant speaking, from teaching thousands of students, and with first children to raise and then grandchildren to dote upon, they lack the singular, monomaniacal focus of their short-lived hero, a young man who willed himself into being and spent his much of his brief life talking. So, with very few wanting to tackle the third hurdle, the Africana crowd, happy with forever spitting the Malcolm mythos, gratefully left the Black biography grunt-work first to the Africana writing machine Marable (who somehow felt he could do a substantial Malcolm X book while editing and writing at least 10 other books), then to the famous Black investigative journalist who, if the final product is any indication, didn’t feel like treating the monumental task as actual work—the way he would have, and demanded others would have, at salaried Newsday. Pass the kufi on the lefthand side.

So how to solve the Malcolm X biography dilemma, to halt these products of recreation over research? To this writer, the answer has all the intricacy of a game of Space Invaders. Here’s the fantastic four: 1) Get $3,300,000 from somebody/somebodies, perhaps, in this climate, some NBA players who will think Malcolm’s Life Matters. 2) Kidnap—uh, pardon, invite—the three most committed writers devoted to the subject—this writer’s votes would be for so-called non-academics Lee, Herb Boyd and Boyd’s Malcolm diary co-editor and Malcolm daughter, Ilyasah Shabazz—and force them into a room together. Then, 3) give each $100,000 for expenses and their national and international research budgets, along with a promise of the million apiece, tucked away safely in a bank account accruing interest, after they finish a collectively-authored, two-volume, 1,400-page biography. Because this writers’ chosen three have done so much already and they know where all the bodies are buried (pun intended), 4) give them only five years to research and write it or tell them that the rest of the advance is forfeited.

This sounds less fanciful than it appears but, admittedly, it does assume that a full Malcolm X biography is a 21st-century African need. Virtually all a major biography requires is extensive time and equally-extensive resources (money, which buys time and travel) for roughly five to 15 years, period. It is not a leisure activity, particularly not if done seriously. Reading the robust first third of Payne’s book convinces this writer that one day a committed scholar will do a full biography of El-Hajj worthy to stand against the biographical works of master 20-and-21st century Black biographers David Levering Lewis, Arnold Rampersad and Paula Giddings. (It is important to note that it took 123 years after Fredrick Douglass’ death for a master historian to come along named David Blight, a serious and committed white scholar—with plenty of grants, time, access to archives and documents private and public, and top publishers, it should definitely be noted—to produce a “definitive” biography, so this future accomplishment will probably have very little public, activist currency.) But for X to mark the two-volume biographical spot, the writer(s) must have the crucial element Payne clearly lacked by choice: a full, comprehensive, demonstrated and, most of all, protracted commitment to history and biography.

A great writer, one who earned his place in history the hard way, has now failed a great orator who did the same because the biographer saw the effort that must go into chronicling a world-historical life, no matter how narrow the focus or theme, as merely an on-again, off-again pastime. Although he left a lot for future biographers to use, the chief mistakes are Les Payne’s, not Allah’s (and not his devoted daughter’s), and they cause a slow chronic pain for those looking forward to having a literary mop to clean up Marable’s still-visible stain.

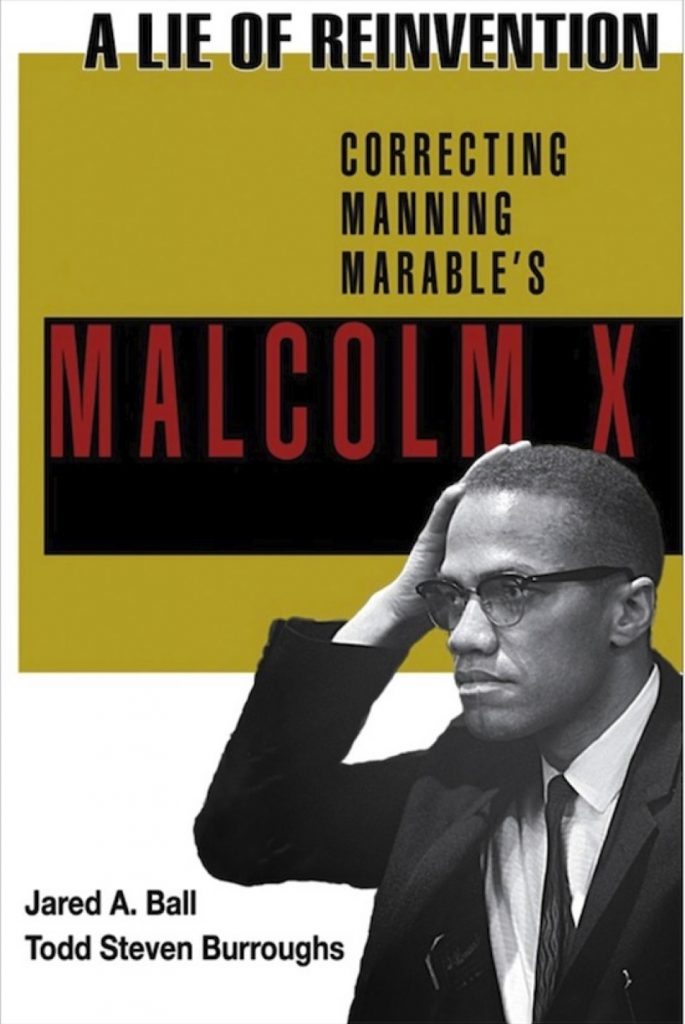

Todd Steven Burroughs, Ph.D., is an independent researcher and writer based in Newark, N.J. He recently completed a draft of Talking Drums and Raised Fists: Mumia Abu-Jamal, A Biography of a Voice and is working on a second Abu-Jamal book, a biographical anthology. He is the author of Warrior Princess: A People’s Biography of Ida B. Wells, and Marvel’s Black Panther: A Comic Book Biography, From Stan Lee to Ta-Nehisi Coates, both published by Diasporic Africa Press. His 2014 audiobook, Son-Shine On Cracked Sidewalks, deals with the first mayoral election of Ras Baraka, the son of the late activist and writer Amiri Baraka, in Newark.

Please share something about the drawing/painting that appears in the middle of this review, including the name of the artist. It appears to be Scot Brown speaking about his book “Fighting for Us: Maulana Karenga, the Us Organization, and Black Cultural Nationalism,” at Eso Won Bookstore in Los Angeles. Is that in fact what is depicted in the image? Is its inclusion here intended to illustrate or refer to the Africana Studies scholar, as described and critiqued in the review? Thanks.

I don;t know about the former, but yes on the latter!

Yep, I intended a symbolic representation! I didn’t know about the context, so THANKS for letting me know about it!

Ago Todd!

I really appreciated your criticism not simply because you identified the gaps in Payne’s biography, but the dreadful state of Africana Studies. The state of Africana studies simply reflects the period of decay and corruption that we are all swimming in today. I have not read any criticism as socially honest or biting since Aldolf Reed’s essay on the so-called New Black Intellectuals and Harold Cruse’s The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual. You are so right, but these are the internal contradictions that we have to slay if we are to be free tomorrow or sometime in the future.

Keep writing, brother, unmasking falsehoods and lies that swirl around us and choke us while we cash our checks.

Thank you very much!