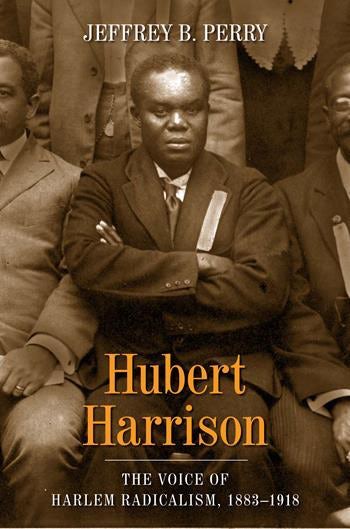

Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918 (Vol. 1, published in 2009).

Hubert Harrison: The Struggle for Equality, 1918-1927 (Vol. 2, published in December 2020).

Both volumes written by Jeffrey B. Perry.

New York: Columbia University Press.

Reviewed by Todd Steven Burroughs

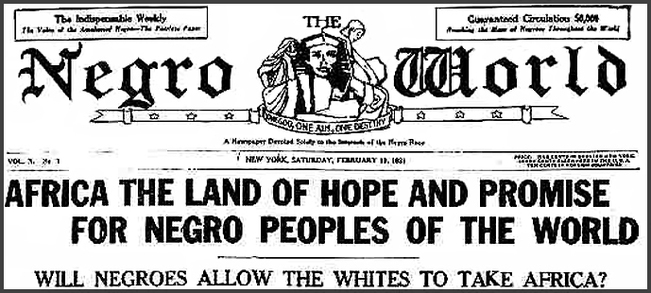

Hubert Henry Harrison had clearly spent too much time on the inside. After years of struggling in poverty, the man who was considered Harlem’s greatest grassroots intellect was hired by the man he had set the intellectual foundation for, Marcus Mosiah Garvey. The post was managing editor of The Negro World, the organ of Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association. He was in time to guide the newspaper’s coverage of Garvey’s massive 1920 conference, the First International Convention of the Negro Peoples of the World. The meeting was perhaps the longest and largest convention African people have ever had.

So what did Harrison privately think of the mass-iest meeting in Black history? The acclaimed orator withdrew his name from the speaker roster in disgust.

The autodidact’s diary shows all of his now-historic bluntness. He called the meeting “the most colossal joke in Negrodom, engineered and staged by its chief mountebank.” Garvey “made an ass of himself and has made the movement a matter of ridicule. He has not the shadow of a program and when he was away from the meeting everything was up in the air. He has plastered the air with lies….The man has a perfect mania for flamboyant publicity. And this, I think, will put a rope around his neck later.”

And that metaphorical rope did come for Garvey, and when it did Harrison, among many of Harlem’s Black leaders, was publicly happy to see good riddance of what he considered bad Black activist rubbish. Harrison, who saw himself as a private witness to the Garvey Movement’s dysfunction, even took the extra step of passing along his UNIA documents to the U.S. Department of Justice to assist in its prosecution! Why? Because, he wrote publicly, Garvey’s propaganda talent “consisted of selling himself” and that he “had a great talent for lying.” To Harrison, Garvey was a fool because of what Harrison saw as the leader’s penchant for pageantry over substance, and that he was “swindling members of his race” through the disastrous and tragic Black Star Line enterprise.

The original hater, Harrison spewed his intellectual venom everywhere, and he made sure everybody got hit. He criticized the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People as a paper-pusher organization, not serious about revolutionizing the Black masses. As alternatives, he founded and assisted now-forgotten groups such as The Liberty League, the Negro-American Liberty Congress and the International Colored Unity League. He shared common ground with socialists, Black and white, but was not afraid to give a public literary kick in the pants, to say, A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen, the publishers of the socialist Messenger magazine, when he felt they deserved it. He consistently wrote and said what he thought, and as a result alienated more than he inspired while he was alive.

All of the above makes him one the most extraordinary unsung figures of the Harlem Renaissance. The scholar Jeffrey B. Perry understood this, and has devoted approximately 40 years of his life—culling through diaries, century-old newspapers, flyers and HHH’s papers, which he helped organize for Columbia University–to produce approximately 1,200 pages (400 pages of text in Vol. 1 and almost 800 pages in Vol. 2, with hundreds of pages of notes and appendices) to pull Harrison’s life and work out from the Renaissance’s basement corner. Volume 1 is an origin story, detailing Harrison’s birth and early life in St. Croix and his time in Harlem educating himself and becoming a well-known writer and activist. Volume 2 is essentially a catalog of his voluminous article writing and particulars his interactions with Garvey and all of the major players of the Renaissance until his very untimely death in 1927 at 44.

Perry points out that Harrison earned his public outspokenness because he was there first, setting the foundation for 20th century Black radicalism: Speaking, writing, editing, organizing, and taking to streetcorner soapboxes.

HHH, his biographer lists with not-undue pride, is only the fourth African-American to receive a two-volume biography. (The others are Langston Hughes, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois.) Why had this preeminent organizer, speaker, writer, editor and author of two major books, When Africa Awakes and The Negro and the Nation, not be significantly documented before? One very easy answer could be the lack of grants to study 20th century Black radical history, funds given predominately to the small group of Ivy League-educated scholars of all races. A second could be Harrison’s public postures: anti-religion and free-thinking, and very anti-capitalist.

It was an exciting time to help found modern Black radical activism. Africans in America were moving away from thinking of themselves as freemen and freewomen (former slaves) and toward being Negroes (second-class citizens). Which way forward for The Race? In Harlem during this time, the direction was away from capitalism (because in America it represented the economic exploitation Middle Passage, slavery and post-Civil War sharecropping) and toward socialism. Garvey had a path—up, you mighty race, and out of America, back to Africa! For his own reasons (promised a rank in the U.S. Army’s anti-radical unit), Du Bois, in his “Closing Ranks” editorial in The Crisis asking Black Americans to support America in World War I, had Blacks gathering around the American flag, and Harrison was highly critical of Du Bois for selling out his people like that. Virtually all the rest veered strongly to the Left. HHH was a warrior in the cause of a race- and class-based direction.

The basics of the Harlem Renaissance period are known to many. World War I, followed by the Red Summer of violent white racist hatred and Jim Crow’s humiliating restrictions created comprehensive, national oppression that Blacks in New York, Chicago and elsewhere responded by producing outsized intellects, activists, artists, and overall local, regional and national political energy. Into this world-historical vortex steps a boy from St. Croix—born in 1883 at the end of the destruction of Reconstruction on the mainland. He believes in and practices the power of self-discipline, self-development, and education for the connected purposes of improvement and liberation. He travels to the U.S. for the latter.

He was the one of first of many powerful Black Caribbean thinkers who would make an impact on the 20th century, a member of an un-official, iconoclastic group that believed in no boundaries and no limitations. With an endless supply of energy and potency (including sexual prowess, since the prideful—and married—diarist kept a record of his romantic conquests along with his schedule and his intellectual ideas), Harrison took his place among the “New Negroes” who were going to advance The Race through thinking, writing and, most importantly, organizing the Black masses. He was right on time to get in on the big bouts: there were four major directions presented in Harlem in his lifetime—religious nationalism (the fledgling Moorish Temple and the AME church, among other Protestant congregations), Black nationalism (Garvey’s UNIA), international Leftist movements (of which one would find Randolph and Owen, among others), and American equality desegregation (Du Bois/NAACP). Together, these activists, who constantly debated and fought each other, shifted the intellectual socio-political focus away from Washington and the Tuskegee Machine to Black America’s new capital, 125th and Lenox.

This northern segregation and intellectual conflagration created the freedom to explore, to agitate, to think freely. In Harlem specifically, the invisible outward barriers led to inward, visible fortification. Libraries, bookstores, living rooms were places of great intellectual utility, where those would get to know each other and know the collective and individual goals of The Race. (Going to the Schomburg then was meeting a librarian who owned a lot of books.) The “Colored” YM/WYCA institutions were homes of necessity, organizing for survival and the creation of a new, 20th-century Black world.

To the New Negro, birthed in this period, public lectures were modern entertainment and mobilization was like breathing. The Race’s collective goals: to stop lynching and all forms of white racist violence against Blacks, end forced segregation, and stop the economic exploitation of Africa, the Caribbean and Black communities in the United States. Yearning for freedom took different forms, creating an intellectual buffet; New Negroes were tasting leaders, ideologies and movements and switching affiliations because there were so many.To the street activists, the direction The Race had to go in was some sort of combination of Pan-Africanism and Socialism. To the established in the suites, such as Du Bois, the way to complete emancipation was toward political and social equality (an end to lynching, the right to vote in all 50 states and legalized segregation). Garvey—whom Harrison correctly accused of “appropriate(ing) every feature” of his Liberty League “that was worthwhile” and applied it to the UNIA—attempted all of the above by trying to get Black America to emigrate to an imaginary Africa of his very own.

Perry documents thoroughly marks Harrison’s trajectory from Black nationalism to Communism/socialism to disillusionment with Communist/socialist white organizations to a quiet or public Black Leftist path. “(T)he New Negro has come forward, neither to whine, to needle, nor to make petitions or vain demands,” he wrote and published as the principles to his ICUL. “but to take his future in his own hands and mold his own destiny by mobilizing his manhood and his money, his resources of head, hand and heart.” His public life is the template for what would happen repeatedly to Black thinkers and artists until the Cold War.

Perry’s volumes, particularly Volume 2, are filled with often-tedious catalogs of Harrison’s book and theatre reviews, articles and editorials, but taken together they have a serious saving grace: he knows and shows the power of Black-owned print publications as major carriers of Black political socialization. (“[T]hose who are allied to unpopular causes—socialists, suffragists, vivisectionists and pacifists—can tell the same story of facts suppressed, distorted, falsified” by dominant (white) American media, penned the man who was constantly writing.) Black and Left periodicals were key to Black political discussion. Mass society yielded mass media which yielded both a mass advertising market and a mass political socialization. But mass media during Harrison’s organizing days meant mostly newspapers, magazines and pamphlets; radio grew exponentially and television was created after Harrison’s death.

The activists made great use of the printing presses, for there was a lot in which to write. The Russian Revolution birthed the Black radical left in the new century, a movement felt in the air after a tornado of pain from violence, rape, theft, land seizure, the growth of the Ku Klux Klan and other white, racist terrorism stirred Black America awake. There were great intellectual fights in pages of The Crisis, The Negro World, The Messenger and in Black papers owned by Washington. Organs, words, vehicles, ideas. The fire of 19th century and early 20th century journalists Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells, William Monroe Trotter and early T. Thomas Fortune would be maintained in both mainstream and radical form in Harlem. The Black press of Harrison’s day debated all of the ideas on the table to free Black people from being choked to death by the American flag.

By Harrison’s birth, the Black press was growing and developing past the early, abolitionist days of Freedom’s Journal and The North Star and turning into mass literary and political vehicles that attempted to connect, organize and educate Black America. Starring Black media roles in the Renaissance saga go to The Negro World, The Crisis, Opportunity and The Messenger. Du Bois’s Crisis, somehow both the NAACP’s organ and Du Bois’ own journalistic fiefdom, is created and grows during this period, as does Opportunity, the organ of the National Urban League.

Harrison attempted two newspapers, The Voice and The New Negro. Later, he would solidify The Negro World until he broke with Garvey in 1921. Perry balances the artistic and the political by quoting from his many, many reviews of books and plays in various periodicals. Unlike many 21st century Black radical intellectuals who speak constantly but do no primary-source research and very little writing, Harrison is a major writer for the Black and Leftist presses of the day. He freelanced for all of the growing Black newspaper powerhouses of the early 20th century, including The Pittsburgh Courier and The New York Amsterdam News.

(Perry does not flinch from a disturbing truth: “One aspect of Harrison’s hiring [at The Negro World] that merits attention is the fact that although he was Harlem’s finest journalist, he was very dark-skinned. He was never able to secure permanent work with The Amsterdam News, The New York News, The New York Age, or Opportunity. He believed that attitudes about skin color were a factor in this.” This is a painful reminder that one of the reasons Garvey wasn’t taken seriously by the Black elite was because, like Harrison, he was a very dark-skinned, working-class man who publicly identified with the dark-skinned, working-class masses.)

When Harrison dies in 1927, the commercializing of the Black press is well underway. Although its editorial pages are still as ideologically strong as ever—The Courier would become legendary in this regard, with more than 10 Op-Ed columnists of many persuasions—the newspapers would become strong mass entertainment and advertising vehicles, with lurid murder stories on its front pages and skin-bleachers a staple ad. Later, mass-market magazines such as Negro Digest, Ebony and Jet would birth the Negro middle-class mass market and its materialistic and social aspirations: fighting for truth, justice and The American Way. Strident opinion journalism would still be part of Black newspapers, but not its primary focus; that would be left to organs such as Opportunity and The Crisis, periodicals that would grow more moderate as the Cold War froze radical dissent in America.

The mid-20th century successors to the radical publications of Harrison’s day were Freedomways magazine, The Black Panther and Muhammad Speaks (the organs of the Black Panther Party and the Nation of Islam, respectively) and Black World, a Pan-Africanist magazine published by the owner of Ebony/Jet that would stain the night sky as briefly as Harrison’s Voice and The New Negro.

So if the first flare burns brightest, Harrison must be credited with leading the 20th century Black radical press as a pioneer before joining Garvey. Ironically, joining The Negro World in 1920 did not put a deserved media historical spotlight on Harrison even though, as Perry thoroughly documents, that the paper under Harrison “was a real key to the phenomenal growth of the UNIA” that year. Only because of Garvey’s mass appeal and its wide circulation, the UNIA organ made the historical cut as the always-mentioned-but-almost-never-assessed father of the mid-to-late 20th century (radical and national) Black press; The Negro World’s flickering historical visibility—apparently its radical, Garveyite content has not been of interest to many American newspaper historians who write books–contributes mightily to Harrison’s footnoted status.It may be amazing to state today, but it’s important to remember that Harrison’s leadership of the Garvey newspaper at the time gave it prestige, not the other way around.

Looking through the pages of Harrison’s life is a painful experience, and not for the obvious reason. The pain is not just from his sudden exit from the intellectual stage after a lifetime of poverty, his death a drastic fade from Black as the Depression, World War II and the Cold War came in rapid succession, playing major roles in directing African-American political aspirations. The pain is compounded when his life and work confirm how the elements expanding greatly in the 20th and 21st centuries after his death—liberal democracy, capitalism, materialism—have so circumscribed the Black political imagination, placing it so very far away from him. After Garvey takes Harrison’s torch, it would be passed to, just to name a few: Marvel Cooke; Doxey Wilkerson; Carlos Cooks; Paul Robeson, Esther and James Jackson, Jack O’Dell and to the staff of Freedom newspaper. And then passed to the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), Brother Malcolm, the Black Panther Party/Black Liberation Army, George Jackson, Angela Davis, and then to the leftist wing of the worldwide anti-apartheid movement and then passed to today’s political-prisoner movement and then, to be charitable, some corners of the somewhat directionless Black Lives Matter.

Perry has opened a time portal to a period that, at times, seems as quaint as an 18th-century church stained-glass window. A man as forgotten as Zora Neale Hurston once was (like Hurston, his grave was originally unmarked for many decades) lived his life within the question: can writing and speaking free us? The answer is disappointing in 2021. Access to Corporate America, elite universities, mass and now-demassified media (particularly the worldwide sports and entertainment components), along with the socio-political dominance of the Democratic Party, has devoured much of any real rebel spirit. (As America has sadly seen, the real revolutionaries as of February 2021 are on the Right.) The Left direction during the Cold War ran straight into the late-century wall of desegregation, of the reinforcement of liberal democracy, of America establishing trade relationships with Communist China, of Vietnam winning its battle to unify itself despite American imperialism, of the fall of Grenada and the rise of a desegregated, liberal-democratic, capitalist South Africa.Therefore, with so many imaginative, liberating doors closed, much of today’s Black brilliant and hopelessly energetic take their desegregated Ivy League educations and go into entrepreneurship, mainstream American politics and law and now, nonprofit “progressive” activism, unthreatening activities by historic comparison and ones that massively reward the individual and his or her family unit, not The Race itself.

But the past is still represented since the African-American experience is non-linear. Today’s stepladders are still present for those who care to digitally look, and small congregants of the faith—HipHop generation Black radical college professors, released elderly political prisoners and other aging Boomer radicals—gather hourly, including at this very moment, on Zoom, Facebook Live and YouTube. Broadcast documentation has become a priority because, the optimistic activist thought goes, it creates an archive of dialogues that can one day lead to worldwide political education. That info builds on the past, and Perry has done a fantastic service to those 2021 intellectual construction workers by reminding them that their Black radical public-dialogue efforts are far from new.

What is different from Harrison’s era is The Race’s collective goal, at least sometimes. The mass belief in creating a new world, not just improving the current one—the rebellious outlook that makes real enemies, that inspires at least sustained mobilization, if not full organization—has wavered in America for decades now, based largely on the election or conduct of a given president and/or a shocking local, national or world event, such as what happened at the Capitol. The intellectually independent are visible but marginalized. There still is no mass-based sustained ideology or energy behind never-ending responses to breaking news, the distinctions between liberal reform, radical reform and liberation lost in the never-ending MSNBC and National Public Radio chatter.

What drove Perry to spend four decades with this extraordinary man is exactly what should drive today’s readers and activist-thinkers to him: that Harrison attempted a clear path forward, believing the future could be, and would be, more humane than the past if one just declared oneself free, acted in and within freedom’s accordance, and worked very hard every day at achieving radical change. So a century of Black radical work began posthumously in 1927 in his invisible name will continue in some form or fashion into 2027 and beyond as the United States, in response, continues to attempt to absorb all of its internal critics.

Hubert Henry Harrison’s America was a segregated, politically regressive nation that worked hard during his life to establish the moderate national Labor Day instead of the radical worldwide May Day. The late 19th-century America began a decades-long pattern of carefully and smoothly smothering what it could not silence in direct rap-battle. Some cases took longer than others, but the United States eventually purchased, among others, the action-figure Douglass and the wind-up dancing toy Washington. It tried hard to capture the Speak-&-Spell Du Bois, but America would eventually place him into its amnesiac recycle bin with Garvey when Du Bois’ substantive vocabulary expanded into a forbidden liberation language and he subsequently broke free to Ghana. The early-20th century reality—an illustrative one—is that the constantly impoverished Harrison was neither purchased nor destroyed by The Powers That Be. Spying on him his entire career via the U.S. Military Intelligence Bureau (assisted by Du Bois and NAACP Chair Joel Spingarn!), they knew it he had no radical army, no strong organization he was leading, no real collection of mass followers; that was left to Garvey, and then to Elijah Muhammad, and then to Malcolm and then Huey and Bobby and…..

So Harrison was allowed to burn out, his intellectual roadmap unsinged but hidden in family closets and basements that Perry was determined to find, organize and catalog. Meanwhile, Harlem in 2021 is gentrified and liberal, poised to celebrate the centennial of its great renaissance of Black/African/Caribbean art and political development in comfortable, accessible, digestible, colonized history morsels.

Harrison asked the question and actively sought an answer: how do Blacks develop radical power in America? The 20th century was a series of experiments to that end made by Black America’s leadership class. Harrison was among the first to wear the white lab coat. In one short lifetime, to be so radical as to be intellectually against Garvey, Du Bois and Washington is quite a hat trick. This reviewer is unsure if Harrison is the end or the beginning, but he is the epitome of what the Pan-Africanist historian John Henrik Clarke, an admirer of Harrison’s, advised: you can change the world if you first change yourself. (To put it in intellectual terms, Harrison was part of a generation of radical political scientists, attempting and creating grounded theory. However, he did not live long enough to see how any of the experiments would play out, what theories would develop from the actions. “By and large, the Common People are the real race,” he wrote. “…They are the dependable back-bone of every good cause and making of many.”) In the almost-mid-21st century, is the experiment over and all political imagination abandoned, regulated only to the university classroom and YouTube? Where does this historic and current energy go to now, a century after Garvey and less than two weeks into the Biden/Harris administration? In this period of strong, unapologetically dangerous post-Trump white nationalism versus a purposely weak, moderate Democratic Party liberalism, answers will come very soon.

What is clear from the view of American historiography is that there remains a whole century of modern and post-modern Black radicalism to document, and Harrison is a correct starting point. His is a model of action twinned with courage, calling out to all writers and historians who will listen and then risk—the only direction that ever matters, the forever-banned one because only substantial danger threatens to shake history to find its radical roots. If freedom is in the attempt, not the victory, HHH’s example is needed desperately and immediately, and Perry is to be congratulated for rescuing him from early 20th-century Black historic trivia and introducing him to this time.

Perhaps the author and subject have shown that individual and collective freedom and self-determination can come from making our demand-manifesto brews too strong for America and any of its white liberal- and Black-leadership buffers to swallow. But if that is the direction for many on the Black left, the question always comes down to accepting the costs of the public panic-attacks from within and without that must result from causing or having the imminent indigestion. Harrison was unbowed and unafraid to go radical and to do it solo—and largely because of that, he was unprivileged in life and, until Perry’s monumental intervention, largely unremembered in death. Harrison was courageous enough to go to all the places where today’s professorial dashikis and “Assata Taught Me” T-shirt wearers still fear to tread.

-30-

Todd Steven Burroughs, Ph.D., is an independent researcher and writer based in Newark, N.J. He recently completed a draft of Talking Drums and Raised Fists: Mumia Abu-Jamal, A Biography of a Voice and is working on a second Abu-Jamal book, a biographical anthology. He is the author of Warrior Princess: A People’s Biography of Ida B. Wells, and Marvel’s Black Panther: A Comic Book Biography, From Stan Lee to Ta-Nehisi Coates, both published by Diasporic Africa Press. His 2014 audiobook, Son-Shine On Cracked Sidewalks, deals with the first mayoral election of Ras Baraka, the son of the late activist and writer Amiri Baraka, in Newark.