The Quiet Before: On The Unexpected Origins Of Radical Ideas.

New York: Crown. 271 pp. $28.99.

Seen and Unseen: Technology, Social Media And The Fight For Racial Justice.

Marc Lamont Hill and Todd Brewster.

New York: Atria. 253 pp. $28.

From Black Power Media, here now the news: The Guardian reported Monday that the Buffalo, N.Y. shooting “has focused attention on the role of Twitch, the gaming platform used by the gunman to broadcast a live stream of the massacre, amid renewed calls for tighter regulation of social media platforms. Twitch allows creators, many with millions of followers, to stream themselves playing video games, chatting with fans, or simply going about their daily lives. The Buffalo suspect [a young white man]…used a Twitch channel to livestream the assault from a helmet camera. Amazon-owned Twitch said it took down the video within two minutes of the violence starting, but by that time it was already being shared elsewhere including on Facebook and Twitter.” Meanwhile, The Chicago Sun-Times reported a week ago that Jacob Blake, a Black man paralyzed after being shot by Wisconsin police, dropped the civil rights lawsuit against the officer who did the deed. “Attorneys for Blake, whose August 2020 shooting sparked the protests in which Kyle Rittenhouse fatally shot two men and wounded a third, and for Kenosha police Officer Rusten Sheskey didn’t say in their court filings why the lawsuit was dropped. Nor did they say whether an out-of-court financial settlement had been reached.”

Rittenhouse took up much public attention last year when he was tried and acquitted. It’s almost forgotten now that it was Blake’s shooting that started the protests that drew Rittenhouse into action to protect white property at all costs. But what is still burned into minds is the footage that was gathered, Rittenhouse’s attempt to channel John Wayne shooting down what he clearly saw as white Injuns. Payton S. Gendron, the now 18-year-old Buffalo accused, and Rittenhouse, the then 17-year-old Antioch, Ill. acquitted, forever will be listed as terror’s teen titans, as YouTube specters. But the tech is still available for all to document immediate action of any kind, so this bloody list will continue to grow.

As America adjusts to living between white-power assassination plots, two serious historical works have attempted to discuss the relationship between technology and radicalism.

Beckerman, senior book editor at The Atlantic, and Hill joined by co-writer Brewster, give their own informed takes, but from somewhat different sides. Spinning through centuries like an out-of-control TARDIS, Beckerman shows that movements and revolutions happen best when ideas are debated and refined—for years or centuries, if needed—outside of any spotlight or platform. Sticking mostly in the present, the scholar-journalist duo argues that tech has created such seismic shifts, has put so much powerful tech to record and broadcast in so many hands, that the new, permanent sunlight is a problematic but now-effective disinfectant, if not bug repellant. Touching ever-so-lightly on media theory (Beckerman is a Media Studies Ph.D. and Hill has an endowed chair in media at Temple), the trio’s intellectual arguments are so individually bouncy and accessible that A.A. Milne’s/Walt Disney’s Tigger would bow down in reverence. Importantly, both books assume that the individual attempted evil or good act is the chief driving agent of our electronic organizing experience, not the psychological underpinnings of the capitalist tech and how that purposeful programming has affected human agency, particularly activism.

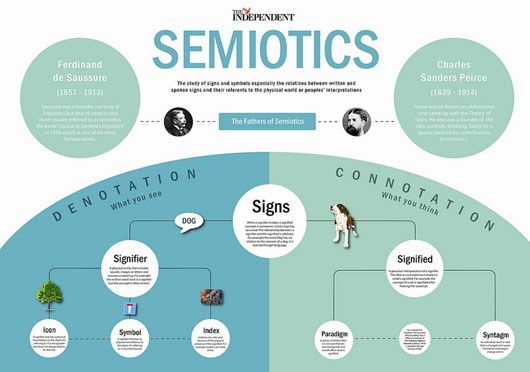

Hill and Brewster attempt to combine semiotics with journalistic detail and background and James Baldwin-level analysis. (They even curtsy a bit to the Master, characterizing Baldwin as a current social-media influencer.) They succeed in producing a hot-off-the-presses document that points toward a new double consciousness—life inside social media versus outside—and often presents a Bizzaro-world white-nationalist reflection of the Black-activist optimism of Allissa Richardson’s now-badly-needing-an-update work in this area; in Seen/Unseen, a large swath of the activists who actually back up their cursors with in-person cursing (and sometimes violent actions) are white racists. Working very fast, the authors provide extensive background and context to the images they discuss—George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery are just two prominent examples—but their attempt for a Baldwin contextual homerun only gets them a ground-rule double. Using present victories, they optimistically postulate that publicly used cell phone cameras and social media could have stopped some of America’s historical horrors.

Beckerman mostly uses the seriousness of the past to prick critical holes in the popular present, this reviewer’s favorite trick. “Every movement needs moments,” he writes, but he makes sure to show the difference between spontaneous actions grounded in serious intellectual work and the performance art of a DeRay McKesson. The savvy influencer-activist “understood [in Ferguson, where Michael Brown was fatally shot] that on Twitter he was a character, and he began wearing a blue puffy Patagonia vest wherever he went. The blue vest worked better than the red shoes and the red shirt he had initially tried, and it soon became part of his brand.” This is the mentality that creates the current problems of Black Lives Matter, a tech-forged movement struggling to become accountable, to be a legitimate part of the Africana struggle continuum, to touch the hem of Harriet Tubman’s and Fannie Lou Hamer’s garments.

The confrontation all three authors have with their at-hand instruments was never far from the minds of 20th-century change agents. While teaching at the University of Hamburg in 1978, Pan-Africanist Walter Rodney explained to his German students in detail why socialism failed in Tanzania. In a new biography that transcribes the lectures, Rodney described in detail how Julius Nyerere’s African socialism—Ujamaa—not only did not succeed but created turmoil. It did not further socialism, explained the professor, but hindered it. “Is it that they failed to grow because of socialism? The argument on the Left is that they failed to transform social structures. They did precisely what other capitalist-intensive plans also failed to do.” Rodney argued that what was important was whether the extended “social structure is mastering the technology and using it for its own purposes or whether that technology appears as an imposition which could weaken peoples capacity to control their environment.” He was assassinated two years later in Guyana, the same year that Commodore released the VIC-20 home computer, an updated version of an earlier model. The ground-level antithesis of today’s social-media activists, a man who died in a car bomb on a street, Rodney was never destined to see the World Wide Web that the world’s children today see as a utility that always existed, like air or water.

The present moment is 44 years away from Rodney’s teachings, and those who struggle are powerful users of technology but simultaneously weakened by it. These two important works of historical linking are clear about that. But before that reality is just chalked up and then ignored as one of capitalism’s many contradictions, the obvious reality that must be faced is that the current tech will inevitably move past this present moment into an uncertain future, one that will determine activism even more than social media and Zoom does now. Can it be true that the golden era of activism might be today—only because of the upgraded ability to organize pixels, to control how to be seen and heard, as if those things are ends within themselves? Beckerman would say a polite and endnoted hell, no, while the Hill-Brewster team would talk about the democratic distribution of the tiny dialing machines and the resulting change within humans: “Technology is now so intimately wrapped up with existence,” they write, “that it has ceased to be something we use and become, instead, a region we inhabit.” This week, that idea draws the reviewer back to the insular, armed white Web worlds of Rittenhouse and Gendron, not to the brave, unprotected Black teen Darnella Frazier, facing the police directly while recording Floyd’s death on a streetcorner.

The techno-optimist argument can only be countered by the most primitive of technology: in-person, breakable bodies composed of hands and feet blocking, kicking or throwing something, in an attempt—in vain or not, in the rain or not—to leap up to get pricked by history’s thorns.

-30-

Todd Steven Burroughs, Ph.D., is an independent researcher and writer based in Newark, N.J. He is the author of Warrior Princess: A People’s Biography of Ida B. Wells, and Marvel’s Black Panther: A Comic Book Biography, From Stan Lee to Ta-Nehisi Coates, both published by Diasporic Africa Press. DAP is scheduled to publish his anthology, The Trials of Mumia-Abu-Jamal: A Biography in 25 Voices, later this year.