Why could Mumia Abu-Jamal receive books on Death Row in the 1980s, 1990s and 00s but is severely restricted in his ability to receive books in 2020, even though he is in general population?

In the Acknowledgements section of Johanna Fernandez’s new book, The Young Lords: A Radical History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press), just released this week, the author wrote that Pennsylvania Prison authorities denied Abu-Jamal from reading and commenting on the final manuscript.

Although she sent it to him care of SCI Mahanoy, the state prison he has resided in since leaving Death Row in 2011, “the prison authorities thought otherwise. I sent it to him in the weeks before the prisoners’ strikes of the summer of 2018, but prison authorities rejected it as a security risk.”

Hunger strikes and work stoppages occurred in prisons across the country in August of 2018 after prisoners rebelled in South Carolina. Seven inmates were killed in one of the most violent prison outbreaks in America in the last 25 years.

The rebellion was partly in commemoration of George Jackson, a renowned revolutionary theorist and activist who was killed in prison in August of 1971. Jackson, a leader of, and organizer for, the Black Panther Party in prison, wrote two books, Soledad Brother and Blood In My Eye, which in the last 50 years have become classics for radical thinkers and Left activists. The author of more than ten works of essays and works of radical history, Abu-Jamal is considered by many on the Left as a post-modern heir to Jackson.

And perhaps that is the problem. “Since those strikes,” Fernandez wrote, “the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections has turned correspondence with prisoners into a labyrinthine operation and made the mailing of a manuscript nearly impossible.”

The action by prison authorities is just the latest against Abu-Jamal, who has had to fight for his First Amendment “writes” from prison since his 1982 murder conviction. In 1995, he was placed in solitary confinement while awaiting his scheduled, and eventually postponed, August 17 execution for writing his first book, Live From Death Row. He was placed in solitary, prison officials said, for engaging in business. In 1996, state authorities banned cameras in prison after Abu-Jamal was recorded for Mumia Abu-Jamal: A Case of Reasonable Doubt?, a documentary that aired on HBO. In 1999, prison officials pulled the public phone out of a wall to stop him from delivering live commentaries on the Leftist newsmagazine Democracy Now!

Since that time to the present, state authorities—including state legislators—have tried repeatedly to restrict his freedom to write books, broadcast commentaries and deliver recorded graduation speeches to progressive colleges. They historically have also attempted to ban any material—pens, pads, and other recording devices—visitors might use in prison in order to limit traditional journalistic and scholarly access to him.

Since 2011, Abu-Jamal—who had written all of his books on Death Row by hand using the cartilage of an ink pen and later by a special typewriter/computer hybrid designed for prisoners—has been off of Death Row and in general population, where he can physically meet visitors and take pictures with them. He continues to record commentaries via Prison Radio.

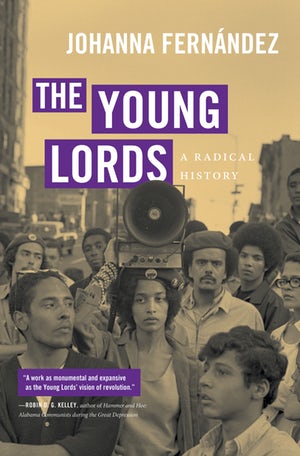

The subject of Fernandez’s book is close to Abu-Jamal’s Black Panther heart. It chronicles the history of the Young Lords Party (also known as the Young Lords Organization), one of the many groups of young radicals who were inspired by the Black Panther Party of Self-Defense. The Young Lords operated primarily out of New York and Chicago, and the author focuses on the creation, activities, and ideology of the New York chapter.

The Young Lords: A Radical History goes into painstaking detail on the history and development of the radical group, focusing on their practical approach to public problems that affected Puerto Rican communities in New York City. Together, the Party members confronted the institutional racism Latinos faced under New York City Mayor John Lindsay.

Like the Black Panther Party, the Young Lords Organization had a breakfast program, political education classes, and a national newspaper. Like the BPP, it also had a platform-and-program list:

- We want self-determination for Puerto Ricans—Liberation on the island and inside the United States.

- We want self-determination for all Latinos.

- We want liberation for all third world people.

- We are revolutionary nationalists and oppose racism.

- We want community control of our institutions and land.

- We want true education of our creole culture.

- We oppose capitalists and alliances with traitors.

- We oppose the amerikkkan military.

- We want freedom for all political prisoners.

- We want equality for women. Machismo must be revolutionary … not oppressive.

- We fight anti-Communism with international unity.

- We believe armed self-defense and armed struggle are the only means to liberation.

- We want a socialist society.

But although the Young Lords were trained in both revolutionary nationalism (Third World Marxism) and self-defense, the Party’s emphasis was not on firearms and open confrontation with the police, but community programs.

The YLO is most known for its two-week takeover of East Harlem’s First Spanish United Methodist Church in late 1969 in an attempt to force the church to be more responsive to its community. More than 100 Young Lords were arrested, but there was no violence.

“In their determination to stoke revolution among Puerto Ricans and other communities of color,” wrote Fernandez, a City University of New York assistant professor, “these radicals transformed the building into a staging ground for their vision of a just society.” The action “gave concrete expression for growing calls for community control of local institutions in poor urban neighborhoods.”

In the half-century since the occupation, many Party members became prominent activists and journalists in New York City. They include Juan Gonzalez, the former New York Daily News investigative columnist and current co-host of Democracy Now!, Pablo Guzman, who was one of the first hosts of then Black-news and -talk 1190 WLIB-AM before becoming an Emmy-Award-winning local television reporter, and Felipe Luciano, who was also a member of the Black nationalist performing group The Last Poets before morphing into a radio and television broadcaster and communication strategist. A young bi-racial lawyer for the YLO, Gerald Riveria, began using a more Latino-sounding name when he became a 1970s star in local broadcast journalism—Geraldo Rivera.

Fernandez was a leader in the successful protests to get Abu-Jamal the medical care he needed to cure his Hepatitis C in 2017. Decades after attempting to implement a 1983 death penalty sentence after a controversial trial for the shooting death of a white Philadelphia police officer in late 1981, months of institutional medical neglect by Mahanoy had threatened to permanently silence the world-renowned writer, by then an international symbol of the radical Left and an elder in radical letters.

In the book, Fernandez said she first met Abu-Jamal when he was still on Death Row. While turning her Columbia University doctoral dissertation on the Young Lords Party into a book, she was encouraged by colleagues to visit and talk to Abu-Jamal, who was a member of the Philadelphia BPP branch and the author of a BPP history, We Want Freedom: A Life in the Black Panther Party.

Back then, he was on Death Row in SCI Greene, “the supermax prison in Western Pennsylvania.” She recalled:

“Within two months, I was in a tiny enclosed room, talking intensely to Mumia behind a plexiglass window. Our conversations centered on uncovering the root of a problem. In hundreds of hours of discussion spanning many years, interrupted only by the annoying clank of prison gate signaling the end of each visit, we explored the broader history of the sixties and the fifty years of conservative reaction that followed.”

Abu-Jamal would eventually allow Fernandez to compile his decades of writings on criminal justice into a 2015 collection, Writing on the Wall: Selected Prison Writings of Mumia Abu-Jamal (San Francisco: City Lights Open Media). Fernandez is the only person to co-edit Abu-Jamal’s collected work other than Prison Radio’s Noelle Hanrahan, the woman who has recorded and distributed Abu-Jamal’s radio commentaries for nearly 30 years.

Wrote Fernandez: “In the movement to free Mumia, I found my political family…..My mind and life have been profoundly enriched by having Mumia as a colleague, collaborator, and friend.”

Todd Steven Burroughs, Ph.D., is an independent researcher and writer based in Newark, N.J. He is the author of Warrior Princess: A People’s Biography of Ida B. Wells, and Marvel’s Black Panther: A Comic Book Biography, From Stan Lee to Ta-Nehisi Coates, both published by Diasporic Africa Press. His 2014 audiobook, Son-Shine On Cracked Sidewalks, deals with the first mayoral election of Ras Baraka, the son of the late activist and writer Amiri Baraka, in Newark. He is working on a journalistic, and, perhaps now, literary biography of Abu-Jamal.