– BLACK POWER MEDIA AND IMIXWHATILIKE.ORG PRESENT AN AFRICAN HERITAGE MONTH SPECIAL –

By Todd Steven Burroughs

(© Main text copyright 2019, 2022 by Todd Steven Burroughs, Ph.D. The “Open Letter” prologue is copyrighted 2020 by the signatories and the 2021 Congressional hearing testimonies in the Appendices are copyrighted by the witnesses. Both supplemental Appendices texts are in the online public domain and, like the Open Letter, are properly credited. The Democracy Now! transcripts are in the public domain but copyrighted by Democracy Now! The digital flyers and Safiya Bukari’s Appendices text, the latter copyright the Estate of Safiya Asya Bukari, are displayed [“printed”] here under Fair Use, as is Joe Piette’s photograph. All Rights Reserved.)

DEDICATION

To Newark’s Amiri Baraka Sr., Seton Hall University’s Leroy Wilson III, Erwin Ponder, Raynette Gardner and Dr. Julia “Judy” Miller, print alt-media’s The Village Voice’s Joe Wood and Greg Tate, Black print media’s Mel Reeves and James G. Spady and Black digital media’s Africology: The Journal of Pan-African Studies’ Itibari Zulu and Black Power Media’s Baba Abdus Luqman, Ancestors All

INTRODUCTION

An Open Letter from Original Black Panther Party Members to Black (Hip-Hop) Artists Who Have an Interest in Our Community (T.I., KILLER MIKE, CARDI B, KANYE WEST, BEYONCE’, JAY-Z, P-DIDDY, LUDACRIS, 50-CENT, and others)

JUNE 10, 2020

Greetings and Solidarity to each of you. In recognition of your individual voice, influence, and cultural following among current generations of Black people/Africans in the Diaspora and on the continent, we salute you.

While we only know you from the public domain, we know that many of you come from backgrounds where you faced poverty, police brutality, lack of healthcare and other forms of oppression like most Black people. We all recognize that we are in a watershed period of economic and government failure, a pandemic and now a resistance movement from which things will never emerge the same.

What we all do in this period will directly impact the fortunes, survival and freedom dreams of Black People, and others around the world who suffer from the same oppression. Whether it’s South American Favelas, South African Shanty Towns, Palestinian territories or the Black urban ghettoes of racist America, capitalism and white supremacy have turned the entire world into a ghetto for the profits of a few. So, we should pay attention to each other, because here, in the heart of racist America we are all we have, and along with our true allies, are truly all we need.

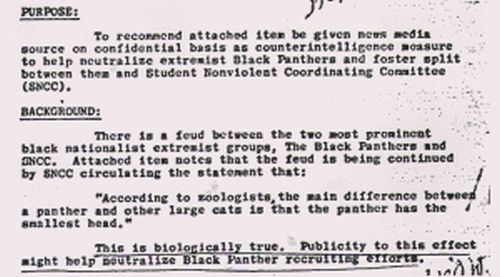

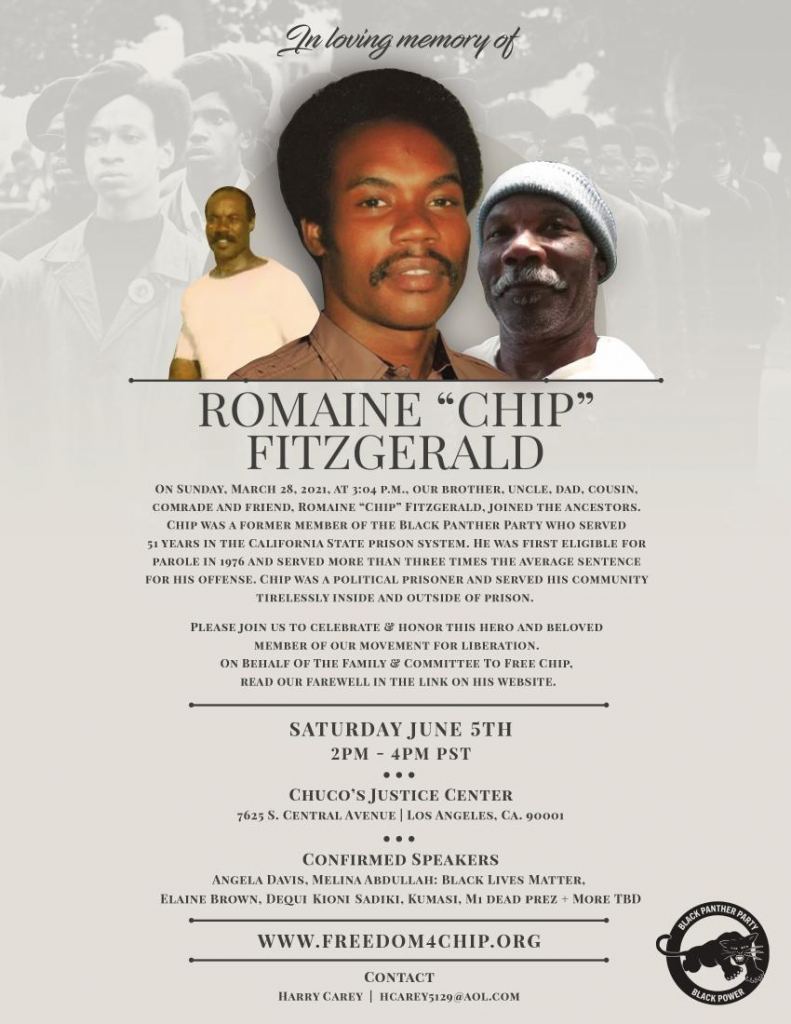

Individually we who write this letter are former members of the original Black Panther Party, co-founded in 1966 by the late Huey P. Newton, and Bobby Seale in Oakland, California. We were targets of the FBI’s infamous Counter Intelligence Program (codename COINTELPRO) which killed many of our comrades, including Fred Hampton, Mark Clark, and numerous other Panthers and revolutionary freedom fighters. We are veterans of government search and destroy missions that forced our beloved Comrade Assata Shakur into exile. We are former Black Political Prisoners who spent decades in U.S. prisons, like our comrades Russell “Maroon” Shoatz [now an Ancestor], Romaine “Chip” Fitzgerald [now an Ancestor], Sundiata Acoli, Jalil Muntaqim [now released], and Mumia Abu-Jamal who are still locked down today. In short, we were on the front line of government efforts to kill and destroy the Black radical movements for civil/human rights including the right to self-determination.

Some of us were also racist law enforcement’s worst nightmare, armed combatants in the revolutionary Black underground, the Black Liberation Army (BLA). Much of our history in our people’s struggle has been kept away from you and seemingly unavailable to your generation as you reinvent what was done in the past. Our people’s enemies haven’t changed, circumstances and conditions have. History never repeats itself – but it damn sure can rhyme.

The question is where do we, Black people, oppressed peoples, go from here? What is to be done? Make no mistake, we are still at war. A war that began when, as Malcolm said, “Plymouth Rock landed on us” and it has continued to this day unabated.

It is our duty as revolutionary freedom fighters to pass on lessons, wisdom, knowledge and experiences to the next generation of freedom fighters, cultural workers and activists. In that manner, an oppressed people can resist domination from one generation to the next without reinventing failures, pitfalls, or the mistakes of the previous generation. It is our enemy’s job to prevent this, and isolate one generation from the other. It is their duty to denigrate the history of militant and radical traditions and burnish the history of integrationists who think we can simply vote our way out of this problem. It is for this reason that we have stepped forward at this neo-fascist moment in history driven by the current crisis of capitalist culture, an ongoing pandemic and the now renewed attention and massive demonstrations brought on by ongoing police murders in our community.

We have chosen to focus this letter on you because our enemies constantly target you to help “calm” the people down. They hope your new class status will outweigh your racial and class analysis. You have a chance to prove them wrong and with your resources and influence, you can be crucial to the collective survival of our people. Tattoos, expensive cars and private jets don’t inoculate anyone from disease and don’t render you bulletproof. We have to collectively provide for our own human agency and not delude ourselves into thinking it’s safer to integrate into a maligned system of greed and dehumanization.

Some may say we as Panther veterans are not the Black people you should be seen talking to. Niggas should know their place we’ve been told and this is one reason that powerless Black folks have sports figures, actors, musicians and bought-off politicians as their public opinion makers. The voices of the disenfranchised are only heard when they rage against the machine that has ground down their lives.

We have all been encouraged by the energy of the Black masses and our allies in protesting the murder of George Floyd, but as each of you is well aware the murder and brutality visited upon our people is nothing aberrational or new. The butchering, torture, and dehumanization of Black people extends back to the days of bullwhips, castrations and mass rape on the plantations of America’s European “founding fathers” and continues to this day. This is the legacy from which modern law enforcement in America derived its overarching purpose, the protection of property and wealth, not people — especially not Black people. No amount of training, social sensitivity, counseling, or smaller police forces will change the current impact of this history on law enforcement. Only our control of public safety in our communities will break this historical context for modern law enforcement. This begins with decentralization of the police, and community control of public safety.

This season of political struggle is indeed about the “Ballot and the Bullet.” To organize the former, (ballot) all progressive and radical forces in America need to come together in a United Front Against Fascism and the militarized police state. This is what the BPP did at the height of the tumultuous sixties, resulting in delaying the outright consolidation of right-wing racist takeover of American foreign and domestic policy.

We must also look beyond solutions that are strictly based on legislative reform, voting, or individual capitalist enterprises. Black folks must survive institutional racist paradigms of power and exercise political and social self-determinant power. The public platforms each of you have can go a long way in creating this tactical and strategic organizing vision. With this in mind, we ask you who have a certain sway over the attitudes and minds of today’s Black youth to do the following:

• Let’s meet and talk through a strategy based on liberating Black People and our respective roles in that fight.

• Let’s create a Pan-African Refugee and Relief Agency where we become our own first responders in times of natural and/or human-made disasters/pandemics.

• Help create a consortium so we can develop a new cooperative economic system where ownership is shared and is directed towards the needs of our people/workers, not consumerist enterprises.

• Support radical and revolutionary Black organizations that have a history of accomplishment and institution building in our community that is independent of major corporate donations, government grants or foundation founding.

• Through your social media reach support the current rebellion in the streets and mass organizing for radical change.

• If you are opposed to property destruction then instead call for massive demonstrations at key government and private installations and give free concerts to ensure large numbers of people come out.

• Work with us and others to create and fund an independent Black electoral platform and candidates with radical demands for Black control and redistribution of this country’s wealth and reparations for Black people.

• Fight for the demilitarization and the decentralization of the police. Create local community boards that can control the hiring, firing and disciplining of police in their community.

• Let’s create not only a new policing paradigm and a community restorative justice model but an end to the prison industrial complex.

These are just some of the things you/we can do to create a united Black Liberation Front to challenge our oppressive conditions in the united states and erase the class divide between the overwhelming majority of our people and those few like you who have some wealth and influence. This is all our opportunity to do what’s best for our people and be on the right side of history.

Original Black Panther Members,

KATHLEEN CLEAVER, SEKOU ODINGA, CLEO SILVERS, JAMAL JOSEPH, YASMEEN MAJID, VICTOR HOUSTON, PAULA PEEBLES, BILAL SUNNI ALI, JIHAD MUMIT, DHORUBA BIN-WAHAD, KIM HOLDER, HAROLD WELTON, HAROLD TAYLOR, ARTHUR LEAGUE, RASHAD BYRDSONG, KHALID RAHEEM, ASHANTI ALSTON.

–As posted at imixwhatilike.org

***

ESSAY EPIGRAPHS:

It’s not knowledge we lack. What is missing is the courage to understand what we know and to draw conclusions.

—Raoul Peck, from the 2021 documentary film series Exterminate All the Brutes

Those days like one drawn-out song, monotonously promising. The quick step, the watchful march-march. All were leading here, to this room, where memory stifles the present. And the future, my man, is long time gone.

—Amiri Baraka (1934-2014), from the poem “Letter to E. Franklin Frazier”

***

IT’S A PAINFULLY POWERFUL thing to realize the obvious: that there is no real relationship between age and significance. The revelation carries even more significance as one grows older and your bond with yourself deepens. I am spending Memorial Day 2021 trying to thematically mine and rhyme disparate memories; the three-day holiday is ample time for an exploration of correlation. It’s been a momentous week heading into the remembering zone—the first anniversary of George Floyd’s murder merged with the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa, Oklahoma massacre. Thanks to Congressman Hank Johnson, a Georgia Democrat, a bill facing history had been introduced in the House for a committee to review, one that would help the few survivors of the butchering gain reparations. Marches and memorials swept across Black America to remember both anniversaries.

The past is not only always present but always available. My news media diet is dominated by two morning news programs: Black Power Media’s ReMix Morning Show and Democracy Now! The radical noise happily destroys the silence of my weekday morning.

I checked out ReMix on May 25th. It was African Liberation Day, a day normally commemorating the 1963 founding of the Organization of African Unity. It is one of those days not sponsored by Wall Street, Madison Avenue or Buckingham Palace. Being a decolonized media forum, ReMix celebrated the day in many ways. One of those was to show a clip of “Black Liberation Army: Soldiers’ Stories,” Black Power Media’s members-only panel the previous weekend with living veterans from the Black Panther Party and the Black Liberation Army–Thomas “Blood” McCreary, Sekou Odinga and Dhrouba bin Wahad. All had done political-prisoner time, but perhaps bin Wahad—part of the Panther 21, a group of New York Panthers framed by the New York Police Department—was perhaps best known.

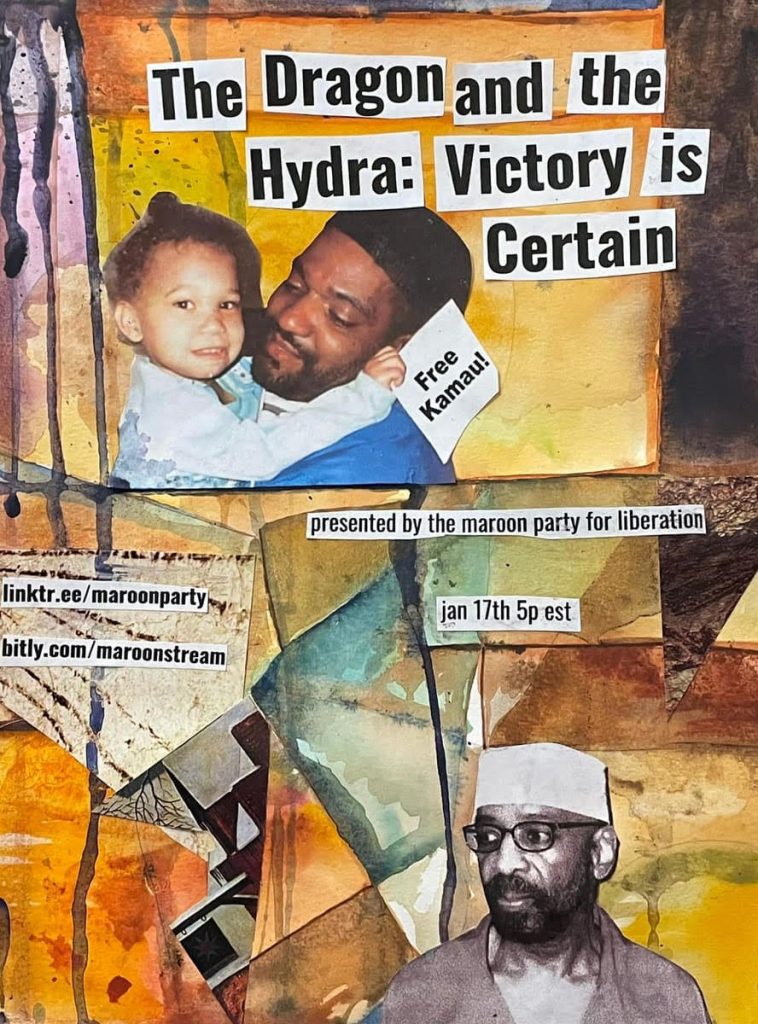

ReMix co-hosts Kalonji Changa, Kamau Franklin and Dr. Jared Ball discussed how proud they were of those who are part of history’s whispers. “I appreciate that they are against the state and they don’t compromise their position,” declared Changa. Franklin said the Black Left and the white-led mainstream Left need to be celebrating these people the way others in America and around the world celebrate these heroes on Memorial Day and all other days; Changa agreed, saying it’s a betrayal of them and their movements if they are not celebrated: “These are our war heroes.” Dr. Ball thought the conversation was a perfect counterbalance to the nationwide, liberal commemorations of the murder of George Floyd. In this public discussion, the three brothers were not imitating the freed slaves who left memorials at Black Union soldiers’ graves in 1865, in what could have been the first Memorial Day in America. Instead, they were publicly acting as free, intellectually decolonized men, honoring secret-warriors still very much alive.

Then the digital “tape” rolled. McCreary explained that the history of the NYC Panthers has to be viewed in phases, with 1966 to 1971 being the period that the Party in New York was a revolutionary group. But the combination of the split between Eldridge Cleaver and Huey Newton, coupled with the never-ending infiltration and harassment from local law enforcement and the Federal Bureau of Investigation—them, as in the enemy of us—brought the New York Party into the BLA phase. After the killings of Black youth and activists started, he remembered, “we decided we were going to take the fight to them.” Telling the audience to ignore popular accounts in the few history books that even bother to mention the BLA, McCreary explained that grassroots Blacks knew, understood and believed in the dark, shadowy infantry. “We had no problem taking that fight to them because under the conditions we were living in—especially in New York, with them killing kids, throwing motherfuckers throwing kids off of rooftops—we said we cannot go on anymore like that…..When we took the fight to them, you found out that they were actually cowards.” The NYC BPP became BLA in 1971, he explained, and that police brutality decreased as a result because authorities now knew there would be real consequences meted out to them directly.

The following day, Democracy Now!, a 25-year-old television/radio newsmagazine that has slowly degenerated in the last five years or so from a grassroots, radical Leftist news forum to an established, “progressive” one, had on as Memorial Day approached Yale University professor Elizabeth Hinton, author of America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s. It’s a well-funded- and -researched book about Black rebellion and she’s the kind of guest the program likes now. With white liberal scholars absorbing virtually all of the scholarly spaces available documenting the Civil Rights Movement, many young, Black Ivy League scholars by 2021 have begun excavating what was Left—the sharper edges of the Black Movement. Many have created intellectual homes there, some by re-interpreting radicalism into antiseptic social science interactions or something else intellectually well-scrubbed and palatable to the blond and the bland.

Violence as a historical tactic was discussed thoroughly, but somehow Frantz Fanon, the guiding theorist of Black insurrection, never came up. Juan Gonzalez, the former Young Lord who is often the historical conscience of the program, brought the conversation into the present but also showed the purposeful impotence of Black response.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Professor Hinton, I wanted to ask you about the lessons for activists today in terms of the response of the establishment, of those in power, to these rebellions. Whether it was in the 1940s or in the 1960s or even now, there is a period of time when the system, because — is taken aback by the mass upsurge and then agrees to certain reforms. In the case of the Rodney King situation, there was a second federal trial of the officers, that sort of sought to calm the public, and as we’ve seen with the Derek Chauvin trial now after George Floyd. But the promises of systemic change rarely occur. And what happens is, the system almost seems to wait until the movement subsides, and then goes back to its old way of doing things.

ELIZABETH HINTON: Yeah, that’s actually a great way to kind of understand the currents and tendencies of history. But I think, you know — and this stems from my previous comment about some of the missed opportunities in L.A. You know, we have to go back to that critical moment in the late 1960s with the Kerner Commission. Johnson’s own National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders basically called for exactly what you’re talking about, that kind of structural change. They said to the Johnson administration and the nation that if we wanted to — if we’re serious about preventing rebellion in the future, we needed a massive investment in low-income communities of color, and not in the form of policing and surveillance and prisons, which is what ended up happening, but in a robust job creation program that — made possible by the mobilization of both the public and private sector, a complete overhaul of urban public schools and a complete transformation of public housing, and the continued support of community action programs that would empower the grassroots to address problems in their community on their own terms with funding from the federal government.

And, you know, unfortunately, time and time again, every time inequality and police violence is evaluated, all of these structural solutions are always suggested, and yet they’re never taken up, as you said. We know what needs to be done. If we’re serious about addressing the problem of police violence in this country and addressing the larger issue of racial inequality, of which police violence is a symptom, then we have to move beyond police reform. We have to support and bring about that kind of systemic transformation that the Kerner Commission suggested more than 50 years ago. We can only imagine what the United States might look like today had policymakers invested in those kinds of robust social programs rather than in policing and prisons. I would be certain that George Floyd would still be with us today.

Knowledge is not lacking here. The system/state reassured on the broadcast forum that used to criticize it consistently, Democracy Now! continued its “global news hour” focus:

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Hinton, the significance of Kristen Clarke, the first African American woman, sworn in last night by the first African American vice president, to be head of the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice? And the significance of this division when it comes to reining in police?

ELIZABETH HINTON: Yeah. So, you know, I think, like Al Sharpton said, we are really facing a turning point in American policing. And the provisions of the George Floyd [Justice in Policing] Act are just a baby step. If we’re serious about public safety, we’re going to have to look beyond the police. Yes, we need to put police violence in check, but we also need to change the conditions that lead to the kind of deadly encounters that we’ve seen all too often throughout our history and, due to the bodycams and the fact that we all have cameras in our pockets now, frequently on our screens.

The program turned to such a frequent frequency: the police killing of Marcus Smith in North Carolina, one of the many, many police killings that happened since Floyd. Smith had been hogtied by police. The Marshall Project, a journalism organization that focuses on the criminal justice system, had released a report about the Smith case called He Died Like an Animal: Some Police Departments Hogtie People Despite Knowing the Risks.

AMY GOODMAN: Marcus Smith’s family is charging cover-up and filed a lawsuit in 2019 alleging wrongful death.

For more, we’re joined by two guests. In Durham, North Carolina, Joseph Neff is with us. He’s an investigative reporter for The Marshall Project who examines the deaths of Marcus Smith and others across the country in a new report headlined He Died Like an Animal: Some Police Departments Hogtie People Despite Knowing the Risks. And in Chicago, Flint Taylor is with us, one of the lawyers for the Marcus Smith family, founding partner of the People’s Law Office in Chicago.

Flint Taylor, start off by continuing to describe that night, where Marcus approached eight white police officers and asked them for help. Within minutes, he would be dead.

FLINT TAYLOR: I can’t see the video as you showed it, but just listening to it, as I have watched it several times, of course, it makes me completely upset. I’m sure that it’s tremendously traumatizing to not only people who are watching, but to the family.

What happened in that case was that these eight white police officers decided that they were going to hogtie Marcus Smith. And this wasn’t something that was unusual in the Greensboro Police Department. We have, in our lawsuit, documented that in the past five years, before the hogtying of Marcus Smith that caused his death, 275 people were hogtied by the Greensboro Police Department and that 68 or 69% of those people were African American, and over 15% of them were suffering a mental crisis, such as what Marcus was suffering.

But what happened in the case, after Marcus died in the hospital — or, actually, lost his breath and stopped breathing, and his heart stopped on the street there — the Greensboro Police Department, spearheaded by the chief of police at that time, watched the video and then chose to put out a press release that, like the first press release up in Minneapolis, ignored and left out the crucial factor that he was hogtied — what they called, in the parlance of the police department, maximum restraint. So they put out a press release that made it sound like Marcus had collapsed: He was suicidal, and he was agitated, and he just collapsed in police custody.

And that was the start of a cover-up that has continued in various forms, has been perpetrated and continues to be perpetrated not only by the police department but by all of the politicians — many of the politicians — the mayor, the City Council, the city attorney and others in Greensboro. And, of course, as you mentioned, we have had a civil suit that we’ve been dealing with for the past two years. We have taken statements and depositions of all the main actors in the case, all the police, the chief of police, the mayor, the city manager. And what’s happening now is that the city wants to put all of that testimony and all of our arguments about why it should not be secret under seal, and they want to hold us in contempt for what they say is disseminating information, information that’s not confidential, information that should be in the public domain. They want to hold us in contempt, and, unbelievably, they want to bar us from practicing law in the state of North Carolina.

And so, that’s where we stand now in this remarkable case, a case that should be looked at along with the George Floyd case and so many other cases where unnecessary and brutal restraint is used. And it’s starting to come to light, thanks to people like Joe Neff at The Marshall Project and you, Amy, so that people can see and understand the breadth of racist police violence in this country.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Joseph Neff, I’d like to ask you. Your investigation uncovered at least 23 deaths that have occurred in the past decade from people being hogtied by police departments across the country. Could you talk about how extensive this practice is?

JOSEPH NEFF: Well, it’s hard to know how extensive it is, because there’s no reporting requirement. For example, in Greensboro, where Marcus Smith died, police do not view the hogtie as a use of force, so they don’t even count it within their own department. We made public records requests from the country’s 30 biggest police departments on use of force, every type of use of force, and we got records back from about 11 of them. So, it’s really hard for the public to know. To find these 23 people who died while being hogtied, we looked in court records. We looked for news stories. That was the — we just had to scrape the web like that to find these cases.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And could you talk about how many departments permit this, or which ones don’t?

JOSEPH NEFF: Well, out of the top 30 departments that we surveyed, the 30 largest, 22 of them explicitly forbid this practice. Another four — Charlotte, Houston, Indianapolis and one other — allow it under different circumstances. So, it’s hard to — I would say that the practice is more common in smaller police departments. The big ones — New York has banned this practice for decades.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to turn to another case. In 2017, Vanessa Peoples was doing laundry in the basement of her Aurora, Colorado, home when police officers showed up for a child welfare check. Peoples told NBC, who you did this project with, Joe, what happened next.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, this is Vanessa Peoples describing this, Joe. And this is Aurora. That’s where Elijah McClain would be killed a few years later, and then another woman describing the same thing happening to her. She was hogtied in front of her neighbors. And can you also talk about the hobble?

JOSEPH NEFF: The hobble is the actual strap that police use to wrap around someone’s ankles, and then they attach it either to the handcuffs or to, in the case of Vanessa Peoples, to a belt around her waist. If you showed this picture to any person in a Walmart parking lot, they would look at it and say, “Oh, that’s a hogtie,” because the feet are pulled up behind the person’s back, and the person is handcuffed behind their back. So, there’s a slight difference in that the hobble is used without attaching to the handcuffs sometimes. But it’s still — if you look at it, it’s virtually the same position.

And Vanessa Peoples, she shouted out seven times during while she was restrained, while they were restraining her, that she couldn’t breathe. And then, you’re right, they took her out, and eventually she was laying in her front yard for all her neighbors to see like that.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Flint Taylor, I wanted to ask you. You mentioned the efforts of the officials to get you — to run you out of North Carolina. But in terms of the — what kind of attacks has the Smith family had to deal with since they sought to find justice for Marcus?

FLINT TAYLOR: Well, Juan, I first want to commend the wonderful strength that Mary Smith, the mother of Marcus Smith, and the father and the sister, Kim and George, have shown, from the moment that they saw the video that revealed that their son had been hogtied. It wasn’t ’til a month later that the video was shown to the Smith family. Mary couldn’t watch it, but George watched it. And that’s the first time that anyone knew, outside of the police department and the powers that be, that there was a hogtie. They had completely covered up not only the fact that he was hogtied but the video itself. They hadn’t released it. They hadn’t moved to release it to the public.

From that moment that the family learned what actually happened to Marcus to this present day, Mary Smith, particularly, and the family, generally, has stood behind justice for Marcus Smith. And I want to say that there’s a remarkable movement on the ground in Greensboro, that is a multiracial, a multigenerational movement, that appears at every City Council meeting and asks questions about what in fact is being done about this case. They stand in front of City Hall every Monday — “Mondays for Marcus” — with banners calling for justice in the Marcus Smith case. And one of the things that the — what’s being demanded by the movement on the ground there is that there be a full apology from the mayor and the City Council for the death of Marcus Smith, there be a memorial for Marcus Smith in the city of Greensboro, and there be just compensation for the family.

The City Council and the mayor have been doing a lot of different diversionary tactics, a lot of misinformation publicly, including slandering the family, and particularly Mary Smith, who is the plaintiff in our lawsuit. We’ve been trying to fight back publicly. And that’s when they came down on us and said, “We can talk, but you can’t.” And I think that it raises — not only does the hogtying and the idea of the different kinds of prone restraints that are used across this country that being so dangerous because of positional asphyxia and sudden death syndrome and all those kinds of activities, but also now we’re looking at an attack on lawyers, an attack on the community, which they are singling out, as well as the community activists who have spoken up — a First Amendment attack.

AMY GOODMAN: Flint, you mentioned Kim Smith, Marcus’s sister. This is Kim speaking to NBC about the treatment of her brother.

KIM SUBER: Imagine your closest sibling, looking at them die. … I had no idea what a hogtie was. I had no clue. That’s how you treat an animal.

AMY GOODMAN: So, looking at this nationally, the scores of people who have died with this use of the hobble, no centralized database about how it is used, Joe Neff, the responses of the police departments to your repeated requests to explain what their policies are?

JOSEPH NEFF: Some departments were very helpful. And actually, in Aurora, they released the data. They actually released the types of restraints that they were using. So, that is how we were able — is one of the few cities where we could actually count the times the was used. And to their credit, the police chief has denounced the practice and fired the officer who hobbled Shataeah Kelly and left her in the well of a car for a drive down to the police station. She has denounced it.

AMY GOODMAN: An astounding story….

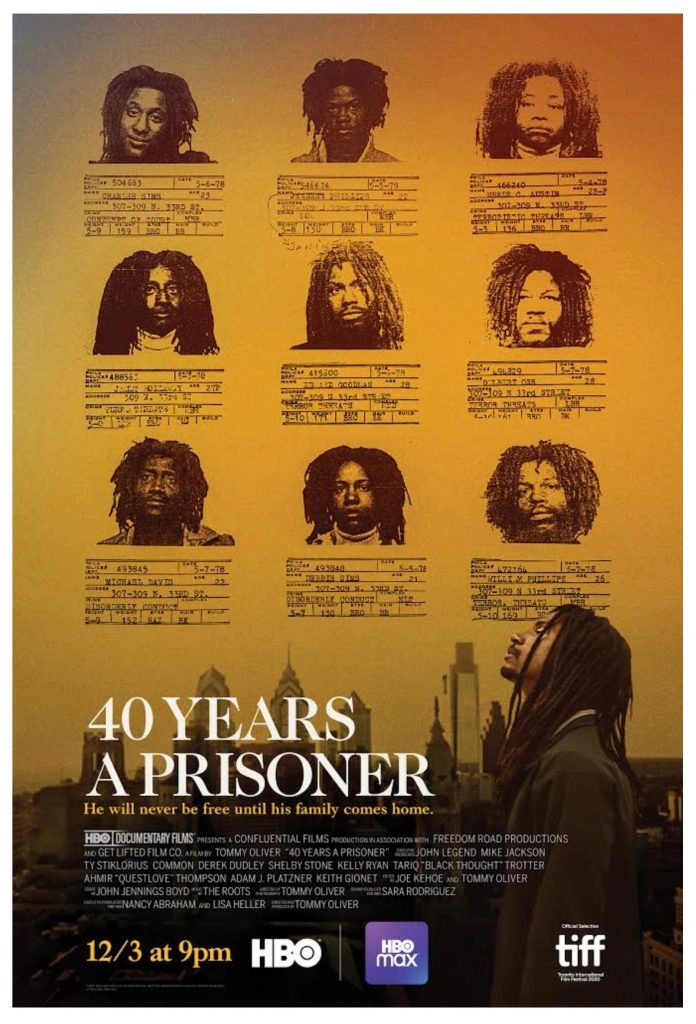

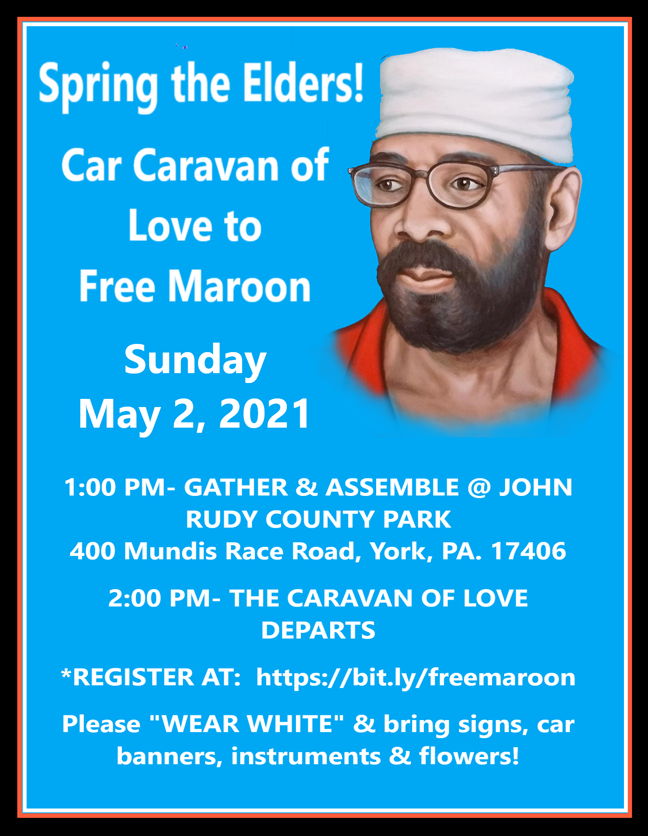

Yes, and one with no consequences for the Greensboro police as of Memorial Day. Meanwhile, Russell “Maroon” Shoatz, one of the Black Left’s political prisoners, was in an emergency situation: he had not gotten his scheduled cancer treatment. The Black political prisoner movement had to interrupt its planning for a Political Prisoner Tribunal in the fall and immediately took charge. The phones began ringing in the Pennsylvania prison and he got the treatment by the Friday before Memorial Day. And Sundiata Acoli, like Shoatz another former Black Panther who has been in jail for more than four decades, was the subject of a proposed car caravan that had to be postponed. These kinds of developments are on Black Power Media’s radar constantly but only make Democracy Now! when one of them is dying.

Thanks to Dr. Ball’s imixwhatilike.org, I once wrote about a “positive” article involving one of these political prisoners, a 2019 book review excerpted and updated here. Albert Woodfox–who joined the Panthers in prison in the 1970s and, as a direct result, was framed into what would be known as “The Angola 3,”–is in 2021, at the age of 74, out and about. His book is called Solitary: Unbroken by Four Decades of Solitary Confinement, My Story of Transformation and Hope. He is speaking and fighting and recovering from being put in Louisiana’s solitary confinement, give or take a year or two for a trial or two, from 1972 to 2016. Woodfox spent the majority of that locked-down time at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, nicknamed Angola–a maximum-security prison that was, and has a long history of acting as a former plantation.

This book’s National Public Radio-ish public face invited America to face up to the abuses of the American criminal justice system and the human rights violation of solitary confinement. It tried to straddle the ideological distance between Panther prison revolutionary George Jackson and liberal prison reform activist-scholar Michelle Alexander, who are both mentioned by the author. However, the autobio’s undercurrent is the visceral hatred whites in power had, have today, and perhaps ever will have, against the Panthers, independent of geography, context, decade or circumstance. The constantly-stoked fear of the long-defunct Party keeps so many white-controlled machines running in 21st century America–pretending-to-be-invisible ones operating in courts of public opinion and law, and proud-to-be-visible ones steadily producing white-supremacy products online and off. No amount of Amnesty International quotes and left-leaning white lawyers embedded in this narrative can obscure that harsh, racist reality, nor should it.

The Angola 3–Woodfox, Robert King (released in 2001) and Herman Wallace–stuck together even when apart. So covert craziness had to replace chicanery. When, in 2013, an elderly and dying Wallace was released (and, it must be emphasized, only after the judge threatened the district attorney who tried to block it with jail), then re-indicted, while on his “free” deathbed, Woodfox correctly diagnoses: “The vengeance by the state of Louisiana against us had long been incomprehensible to me, but this move pushed at the boundary of sanity.” Right, because many Blacks see powerful whites’ Panther obsession, no matter how many decades later, as a sickness. It is absolutely that, and it is also a half-century-old, tried-and-true way to scare older whites and exert political and legal leverage over any Blacks who become radicalized and resist, either in the streets or in prison.

Woodfox, who, at one point in his 44 years of suffering, had to drink water out of the toilet, is unsparingly honest about his criminal past. Yes, he admitted to years as a thug and a crook, one who once held a gun to a deputy’s head. He was mesmerized by the Panther’s image and enveloped in its shadow. And he paid the price in his trial.

Time halted and became twisted in the pages. The reader’s frustration builds as the emotional and physical casualties mount. “In prison, you are part of a human herd,” Woodfox recalls. “In the human herd survival of the fittest is all there is. You become instinctive, not intellectual. Therein lies the secret to the master’s control. One minute you’re treated like a baby, being handed a spoon to eat with or being told where to stand. The next, with utter indifference, you’re being counted several times a day—you have no choice, you have no privacy. The next moment you’re threatened, pushed, tested. You develop a sixth sense as a means of survival, instincts to help you size up what’s going on around you at all times and help you make all the internal adjustments necessary to respond when it will save your life, but never before. Taking action at the wrong time could get you killed.” Although Woodfox’s prison world is very violent, his internal growth and power (and the types of psychological and physical warfare against prisoners waged by guards and wardens) are not unfamiliar to those who have read any samples of prison biography, including Nelson Mandela’s autobio. Since the Panthers originally carried law books on patrol in Oakland, it’s not surprising that Woodfox decides to become an expert jailhouse lawyer.

There are plenty of details about how prison authorities framed the Angola 3, in jail for separate crimes before they became politicized, for the 1972 killing of a young, white corrections officer. Coincidences abound after decades of attempts at legal redress: Woodfox’s FBI files destroyed, and most of the evidence that could clear the Angola 3, lost. The group’s international campaign came late but struck the Black Lives Matter Zeitgeist.

The book’s epigraph defies its Amnesty International-ish marketing: “It has been my experience that because of institutional and individual racism, African-Americans are born socially dead and spend the rest of their lives fighting to live.” Woodfox infuriated authorities by doing three things: refusing to neither break nor die, continuing to believe in and publicly proclaim the principles of the Black Panthers, and consistently and publicly resisting racism and human rights violations in prison. The Louisiana Panther-no-longer-with-a-Party forced himself into an emotionally moderate existence; for decades he made himself into something as cool and hard as the metal used in prison doors.

There was no happy ending to enjoy. Even Woodfox’s 2016 release is tainted with legal and political fraud on the part of the Louisiana corrections officials. His lawyers and advisers persuade him to plea “no contest” to the correction officer’s murder because he might die in prison if he continued to attempt to prove his innocence. So he walks out into a new century, victorious and compromised because of the vicious hatred white law enforcement had for the Party and any ideological fellow travelers. Meanwhile, all those who tortured Woodfox are unpunished, because all they did was either legal or allowed. I didn’t as much finish the book but finally throw it down in disgust.

None of the liberal homilies and blurbs that surround inside and outside the covers demand that the individuals at Angola be punished along with the reform of the system. Sadly, neither does the book’s author. Instead, corporate prisons, right-wing politics, and the finances behind jail construction and prisoner occupancy, amorphous entities all, take the rap. For the organized anger it wants to generate, Solitary wants an all-too-safe ABC Afterschool Special ending to such an NC-17 racist horror tale. So after all the Black resistance and courage displayed, the book’s message is that City Hall can be overcome but not defeated, particularly if you publicly embrace the Party.

Time has yet to thaw two years later. Woodfox’s house of horror is average for a Black American political prisoner—an experience I was intellectually introduced to as a young man growing up and going to Black political-cultural events in my native Newark, New Jersey. Loosely described, political prisoners are either a) radicals who were framed with killing police or some other felony because the state considered them dangerous; b) radicals who killed police or committed some other crime as a result of their political activity, which resulted in them being treated harshly in the courtroom and in prison, or c) criminals in prison who became radicalized and, as a result, have been continually punished by prison officials and parole boards. These descriptions overlap, creating complex definitions. Not the easiest heroes to admire if you grew up being taught to worship Movement doves such as Rosa Parks and John Lewis.

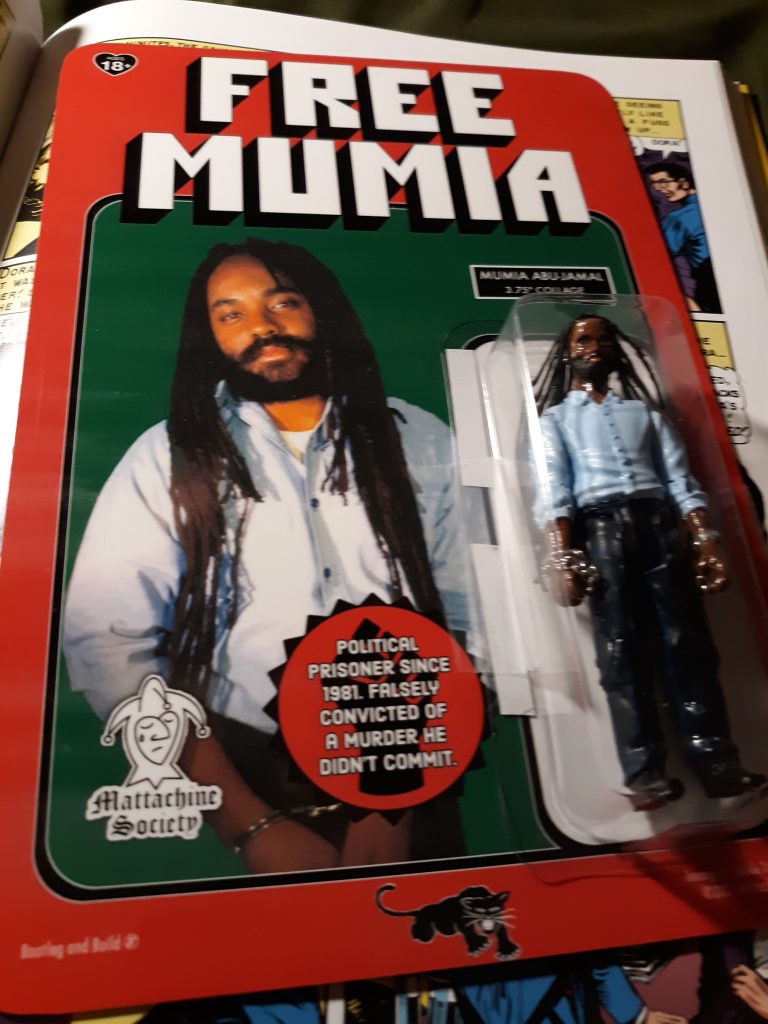

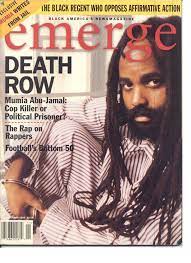

In graduate school in Maryland, I began to learn more about a political prisoner who would define my life’s work as a historian—Mumia Abu-Jamal, an imprisoned writer and broadcaster who prison officials couldn’t stop punishing for his effectiveness. Twenty-five years later, I finished a draft of a journalistic biography and a general anthology about him filled with some of the world’s experts on his life and case.

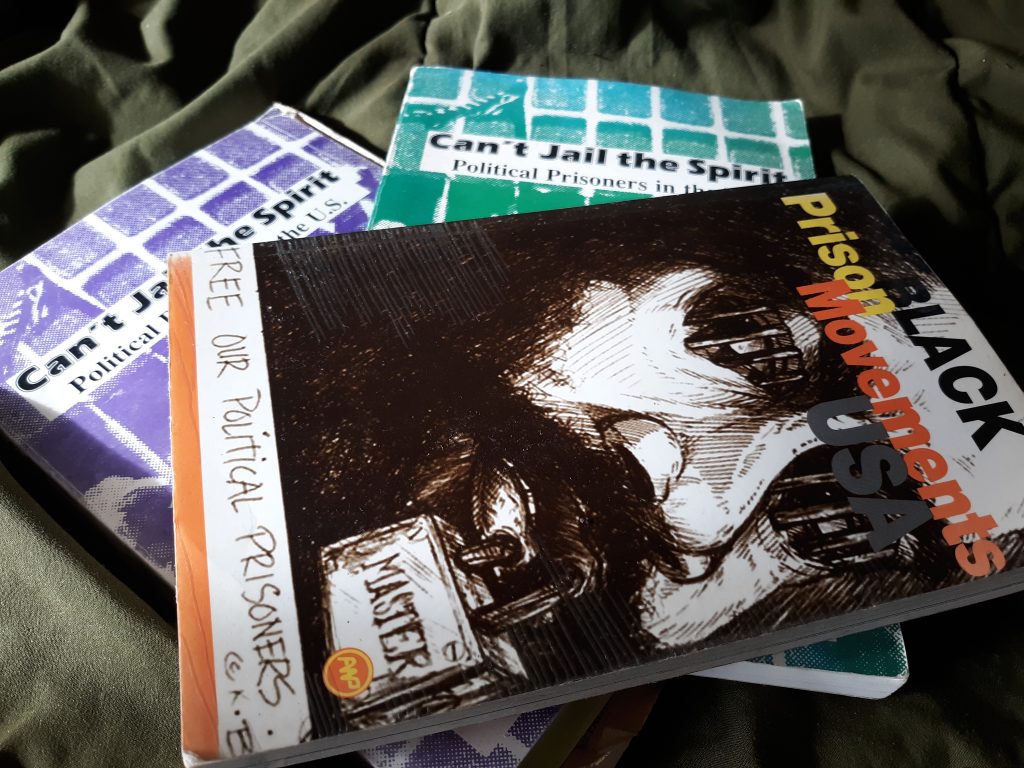

I would also find grassroots materials about the political prisoner movement. The Internet was still developing in those days and the World Wide Web was at its mid-1990s infancy. So information was analog and static. I don’t know how I found so many things I would mail away for, but I would keep them, particularly if they were in book form.

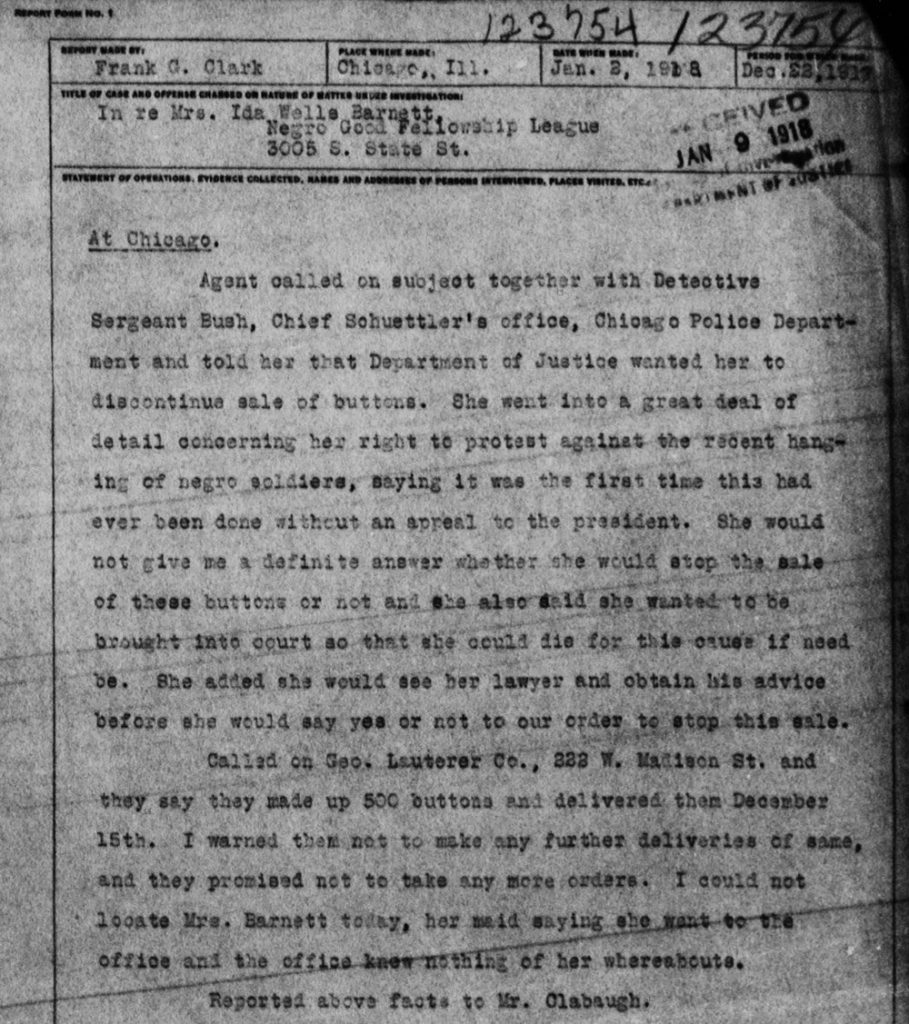

One such reference book was Can’t Jail the Spirit: Political Prisoners in the U.S.: A Collection of Biographies. Another reference book—which called itself a “bookazine” because it was a journal published by the book publisher Africa World Press—was called Black Prison Movements, USA. In those mini-encyclopedias, which profiled Black, Puerto Rican, Native American and white political prisoners, I learned about: The test of wills—the state versus the individual Panther or radical; how writin’ is fightin’ in the documenting Party/prison life; their backgrounds and the “need” for the government’s movement-disrupting counter-intelligence program (COINTELPRO); their jailhouse lawyering attempts, and much more.

I am remembering these compilations now because of the amount of time that has passed and how the George Floyd murder brings back all of the now-forbidden acts of the Panther past. Was it bin-Wahad who on Black Power Media’s Renegade Culture with Kalonji Jama Changa and Kamau Franklin just asked why didn’t one of those bystanders just toss a brick at Derek Chauvin? I understand his decolonized point: Chauvin would have quickly gotten up and Floyd might have remained alive but then at least one of those bystanders would have been beaten, gone to jail or through a gunshot wound or four taken Floyd’s place in local death, if not in world history.

These now-outdated, obscure books, profile-packed with now-Ancestors (such as MOVE 9 member Delbert Africa and former Black Panther Romaine “Chip” Fitzgerald) and subsequently released, are filled to overflowing with those who had flung their bricks without any thought of consequence. It’s the knowledgeable result of rebellion that froze the Floyd crowd—if you violently interact with police, if you defend yourself or members of your community, you will die at the scene or never again see freedom—so the brick stayed on the ground, and the African-American purposely digressed to Black and then to Negro. Frozen in highly-reluctant self-restraint by an organically understood history of the punishment doled out to defiant slaves. Freeze! Police!

There were no Black Panthers at the murder site of Floyd to foment self-defense. But at least Darnella Frazier stood her ground with a smartphone in her hand, a teenage witness not afraid to stare a policeman in the eye.

Her social-media statement on the first annual commemoration of Floyd’s death:

A year ago, today I witnessed a murder. The victim’s name was George Floyd. Although this wasn’t the first time I’ve seen a Black man get killed at the hands of the police, this is the first time I witnessed it happen in front of me. Right in front of my eyes, a few feet away.

I didn’t know this man from a can of paint, but I knew his life mattered. I knew that he was in pain. I knew that he was another Black man in danger with no power.

I was only 17 at the time, just a normal day for me walking my 9-year-old cousin to the corner store, not even prepared for what I was about to see, not even knowing my life was going to change on this exact day in those exact moments… it did. It changed me. It changed how I viewed life. It made me realize how dangerous it is to be Black in America.

We shouldn’t have to walk on eggshells around police officers, the same people that are supposed to protect and serve. We are looked at as thugs, animals, and criminals, all because of the color of our skin. Why are Black people the only ones viewed this way when every race has some type of wrongdoing? None of us are to judge. We are all human.

I am 18 now and I still hold the weight and trauma of what I witnessed a year ago. It’s a little easier now, but I’m not who I used to be. A part of my childhood was taken from me. My 9-year-old cousin who witnessed the same thing I did got a part of her childhood taken from her. Having to up and leave because my home was no longer safe, waking up to reporters at my door, closing my eyes at night only to see a man who is brown like me, lifeless on the ground. I couldn’t sleep properly for weeks. I used to shake so bad at night my mom had to rock me to sleep. Hopping from hotel to hotel because we didn’t have a home and looking over our back every day in the process. Having panic and anxiety attacks every time I seen a police car, not knowing who to trust because a lot of people are evil with bad intentions. I hold that weight.

A lot of people call me a hero even though I don’t see myself as one. I was just in the right place at the right time. Behind this smile, behind these awards, behind the publicity, I’m a girl trying to heal from something I am reminded of every day. Everyone talks about the girl who recorded George Floyd’s death, but to actually be her is a different story.

Not only did this affect me, my family, too. We all experienced change. My mom the most. I strive every day to be strong for her because she was strong for me when I couldn’t be strong for myself.

Even though this was a traumatic life-changing experience for me, I’m proud of myself. If it weren’t for my video, the world wouldn’t have known the truth. I own that. My video didn’t save George Floyd, but it put his murderer away and off the streets.

You can view George Floyd anyway you choose to view him, despite his past, because don’t we all have one? He was a loved one, someone’s son, someone’s father, someone’s brother, and someone’s friend.

We the people won’t take the blame, you won’t keep pointing fingers at us as if it’s our fault, as if we are criminals. I don’t think people understand how serious death is…that person is never coming back. These officers shouldn’t get to decide if someone gets to live or not. It’s time these officers start getting held accountable. Murdering people and abusing your power while doing it is not doing your job.

It shouldn’t have to take people to actually go through something to understand it’s not ok. It’s called having a heart and understanding right from wrong.

George Floyd, I can’t express enough how I wish things could have went different, but I want you to know you will always be in my heart. I’ll always remember this day because of you. May your soul rest in peace. May you rest in the most beautiful roses.

And a final meanwhile to end the many Memorial advance week: one of the leaders of the Black Lives Matter movement, Patrisse Cullors, announced she was stepping down from the group’s $90 million foundation. Like Laureen Hobbs, the Angela Davis parody in the satirical 1970s film Network, she decided to literally go Hollywood. Cue the Marvel Studios’ Winter Soldier’s activation code words, but this time to keep the freeze going: …..grants….fellowships….endowments…….television……film…..

Negroes are restricted and Africans are free. That’s a very reductive statement that obscures the complexity of current America. After all, mainstream journalists write issues around American political prisoners, depending on the size of the rally, but until the courts step in, often view them the way they view other convicted murders—as controversial and guilty, not framed. Because of the enclosed, publicly-forbidden nature of the phenomenon, there is frost thawed only by obits. Why won’t writers write about them and the abuses they are under regularly? Political prisoners around the world—including bombers!—are written about, assessed, studied in central spaces. Where are the Black public intellectuals, the major Black nonfiction writers? The answer is simple: the subject’s a dead-end, literally. A brick will be thrown into your writer/public intellectual career if you choose to seriously spotlight Black radicals who may or may not have killed white police officers and who may all die in prison for that slave-rebellious act.

Those political prisoners in those reference books I read in the 1990s and early ‘00s were, and are today, the freest Black people to exist in the modern and post-modern era, and they have the punishment record to show for it. From 1962—the year Ruchell “Cinque” Magee, Angela Davis’ original co-defendant, was arrested—to 2022. Americans of African descent that struggle to be actually free—by that, I mean, “Jonathan Jackson-level free,” to make an unfettered attempt for your liberation and not beg for it—will not exist again for 100 years because liberating language has now been colonized via establishment borders of “violence” versus “nonviolence,” a well-constructed and well-funded Civil Rights Movement internment camp. So those outside that ideological cage are frozen in real ones, restricted, suspended between life and death. Half a century of overlap between purposely-forgotten people, ideologies and documents. So questions arise from these lives that have no easy answers. What ideas link them to: Us? You? Them? Each other? What do we see about the past, present and the future from their eyes? What freedoms do we fight for and what freedoms should we fight for? What should the standards be? These questions long ago were suppressed for the sake of pol-white ppl company and its symbiont, Black middle-class advancement.

I collected biographies, autobiographies memoirs and writing collections of these men (and Assata Shakur, and Safiya Bukhari, and Angela Davis, and…) over the decades because I wanted to find some of the answers to the questions above. I also wanted to balance the lives of this slowly dying breed with the writing that I saw in the books written by those on the outside: Leftist scholarly articles about the society (which would include prisons) and agitprop Op-Ed or extended essays.

My goal mirrors theirs—exposure as activity, with the illusion of some sort of utility—but it’s more critical. Angela Davis called the 1971 book compiled in her honor and with her help, If They Come For You in the Morning, as an organizing tool and teacher about the nature of prisons and how they were used to oppress Blacks and the poor—an expansion of the political-prisoner idea to include all incarcerated victims of institutional racism. This particular journey is one of seeing and commenting on echoes: Woodfox models Malcolm X by educating himself in the prison library. He had been in prison so long, he could analyze Eldridge Cleaver, George Jackson, Fanon and Malcolm as historical figures. Cycles.

So this is not so much a search over half a century of Black radical literature, of biography and autobiography containing prison life and its horrors and hopes, but more of a professionally reckless decision to publicly dip my hands into intellectually radioactive matter in order to properly see a slideshow of the tension between the rational and irrational. To talk about armed self-defense and physical attack against oppression while surrounded by attempts at representation and witness. “The guns are not about killing people,” explained Panther 21 defendant Jamal Joseph to his childhood pastor who had asked. In a powerful flash of the naive honesty often attributed to youth, Joseph then said: “It’s about trying to inflict a political consequence.” Remembering his mid-20th century life in a 21st century Panther memoir, Joseph connects to McCreary by way of memory’s militant consistency. Documenting such diagonals is the goal here, with the result being a critical manifesto-ish construct disguised as nonfiction, a trip through the guidebooks of memory.

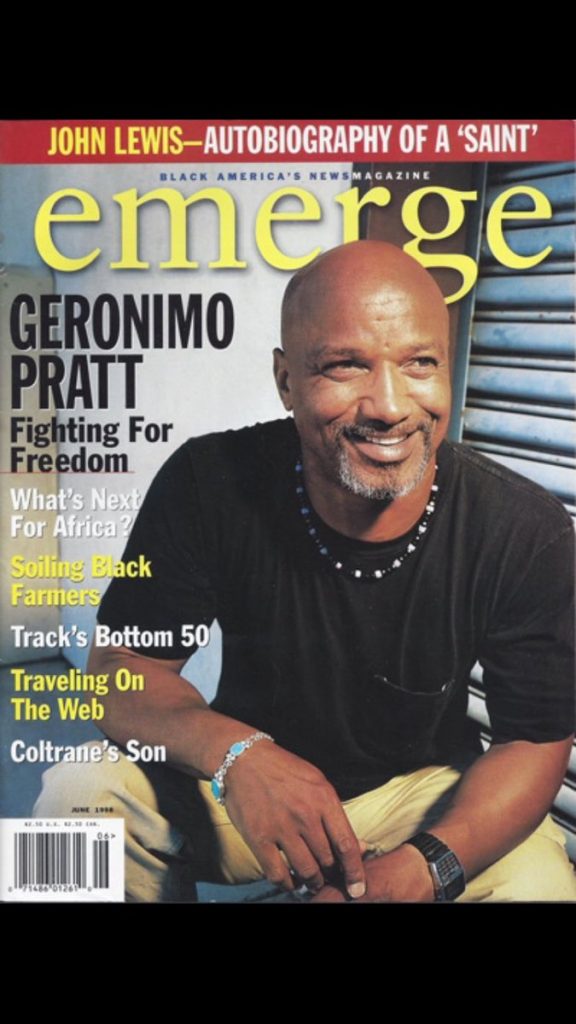

If America has its way (and for the most part it has), the two choices given to political prisoners are to die behind bars or die shortly thereafter, like Wallace and Delbert Africa did! Some are defying that, most notably Jalil Abdul Muntaqim, and the surviving and now “free” members of the MOVE 9. But others are on the precipice of being reduced to these small description paragraphs that double as advance-obit drafts. Here, time hurts instead of helps, because of the relationship between ideas, fear and pain; there is constant private wrestling with despair, dread, suffering. Sometimes there are rays of mainstream hope—like Elmer “Geronimo” Pratt being mentioned once by future lawyer Freddie Brooks on NBC’s A Different World. But that representation—that acknowledgment—did not free him; serious legal work fed by the grassroots forged the key.

Then/now tensions are exposed from the perspective of the jailed Cats: liberal democracy versus radical change, freedom versus liberation; “change” versus revolution. Black Americans now want “change” (comfort) while Palestinians, forever without comfort and only getting the international spotlight during bloody public skirmishes, want a liberation struggle. Mentioning either jailed Panthers or contained Palestinians out loud and privileging them as worthy of extended discussion is an act of public defiance. The intellectual frost that Democrats in office can’t thaw is this: Black America has lost control over developing their own ideas the way Ta-Nehisi Coates said Blacks have no control over their own bodies. It is time to extend these memories beyond Facebook, Twitter and Instagram posts, and now Zoom narrowcasting and YouTube broadcasting, the new public spaces where most of our personal histories now reside. So finally, this is an analog future quest, a treasure hunt for purposeful anachronism.

MY PURSUIT STARTS IN the newsstand glossy-mag 1990s with my emerging-adult dreams of becoming a successful writer. I was a huge pack-rat/hoarder then, living alone in a ground-level studio apartment in Hyattsville, Maryland, with piles of newspapers, magazines and books. I immersed myself in print culture because I saw myself as a future history book author and magazine writer and I wanted to create my own nonfiction canon from which to draw. Instead of going to graduate school to get a comfortable job, I did the opposite: I had left a very cushy general assignment reporter job at a large daily newspaper in Newark and moved to Maryland because I sought to wedge myself into the continuum of Black letters, and what I had typed thus far in my small inner-city pond was not enough. So I focused on my Master’s and Ph.D. degrees at the University of Maryland at College Park while print culture was on the verge of being digitally transformed thanks to the birth of the Web.

From one of the sides of my mind came the discovery of those two books. Spirit was the type compiled by small groups of activists who were keeping their objectives alive through Pacifica Radio, flyers, small books and pamphlets. It was published by a group called the Committee to End the Marion Lockdown. The prisoners profiled themselves and the committee would update the book as prisoners died or were released. I had two different editions: the fourth edition, originally published in 1998 (the time of the Jericho Movement, a national mobilization for political prisoners) and the fifth, published in 2002. Black Prison Movements, USA, was co-published by Africa World Press and The NOBO Journal of AfricanAmerican Dialogue, the academic organ of the Network of Black Organizers. Today, all of this work is done online with websites (Jericho’s website seems to be the focal point for most information on American political prisoners), Zoom, YouTube and Facebook, with Twitter as a way to shoot news bullets.

Spirit was first produced as photocopies in 1988 as a way to stop the denial of American political prisoners. (“If political prisoners did not exist, then who were these people?”) The book format came because of the support of the Prisoners of Conscience Project. That was directed by Reverend Seiichi Michael Yasutake. This edition was published in the wake of Jericho ’88, an important mobilizing event I had not heard of at the time. My copy listed those who had been freed since the first edition: it had included names I had heard of (Herman Ferguson, bin Wahad, Pratt) and many I had not heard of (Kazi Toure, Alan Berkman, Jaime Delgado, Dora Garcia, Barbara Curzi, Patricia Gros, Ed Means and Carol Manning). The book explained how the organizers debated over the criteria of calling someone a political prisoner.

Reverend Yasutake did not equivocate in Spirit’s preface: the people listed, he wrote, are inmates not because of wrongdoing, “but because they did right by working to empower the powerless and the poor and standing up for their rights as human beings. Puerto Rican political prisoners and prisoners of war seek independence for their nation of Puerto Rico, still a colony of, and exploited, by the U.S. The American Indian Movement prisoners and African American political prisoners seek self-determination for their people.” To those unfamiliar with the nation’s real Left, these sentences must have seen to come from another universe in the era of William Jefferson “Black Like Me” Clinton and the emergence of neo-liberal Black politicians such as Virginia Governor L. Doug Wilder, U.S. Senator Carol Moseley Braun and the expanding Congressional Black Caucus. “The hundredth-year anniversary in 1998 of the U.S. conquest of Puerto Rico and Hawaii, among other nations,” continued Yasutake, “is an opportune time for us in the ‘outside’ to join forces with political people inside prisons in struggle against all forms of colonialism and for justice.”

Today viewed as a martyr to the political-prisoner movement, Bukhari wrote in Spirit: “Sacrifice is an intricate part of a people’s struggle for freedom, justice and independence. An inherent part of this sacrifice is the death of the I for the we and the me for the us.”

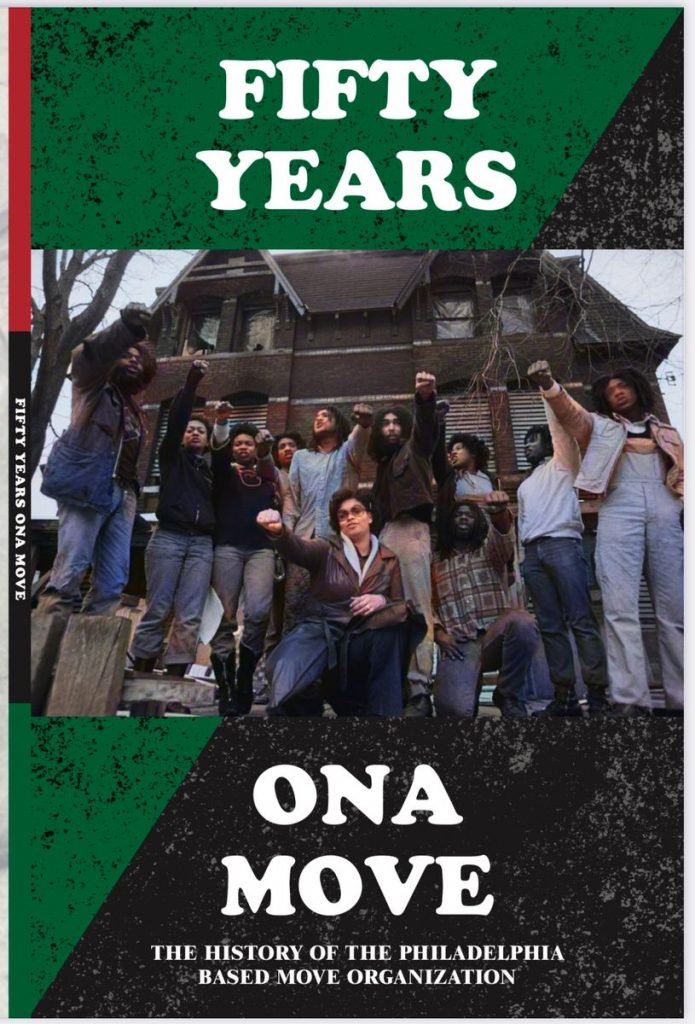

More essays, on Mexican/Puerto Rican political prisoners, then the list. Then the list of autobios in categories such as Native Americans and New Afrikans/Blacks. Thumbing through it, I discover MOVE 9 members Debbie Sims Africa and Delbert Africa and former Black Panther “Marshall” Eddie Conway. One political prisoner listed here I would eventually meet in San Francisco, thanks to Noelle Hanrahan of Prison Radio, without remembering him as being on the roster: Claude Marks, now the director of Freedom Archives, an important international audio collection of radical voices.

The Black Prison Movements “bookazine” carried an article from bin Wahad. I had the honor of breaking bread with him once, thanks to Dr. Ball. His contribution was the text of his comments to Mandela when the African National Congress leader visited New York City in 1990. “Today, U.S. political prisoners have no voice, they remain invisible. The ANC and the anti-apartheid forces in South Africa have always kept the names and faces of your political prisoners in public view. We should learn from your example.” This was four years before Abu-Jamal was muzzled by NPR and five years before his radio commentaries, recorded and produced by Hanrahan, were distributed on cassette by Prison Radio and Equal Justice USA, another activist group, around the pre-Web-audio world. By writing and broadcasting whole Op-Eds about his fellow political prisoners, Abu-Jamal, who always talked about other people’s cases, attempted to “mainstream” many of these folks.

***

The fact that most of these activists in these reference books are Baby Boomers, post-World War II babies, is far from surprising. Birthed in American freedom and the attempted genocide of World War II’s Nazis, they grew up watching on the new-fangled television former radio stars Superman and the Lone Ranger, both costumed outlaws who took American justice into their own hands. Newspapers were plentiful, and they read about the struggles across the world for freedom after the formation of the United Nations. They took improvisation from blues, jazz, and rock ’n’ roll/doo-wop: rebellious music could be purchased and played on something called a record player. Radio and television were dominant mediums, and they had spare time to absorb them, including Black radio and the Black press. Because they didn’t have to work to support their families, they were privileged regulars at public middle and high schools and public libraries.

New spaces created by American growth and prosperity created new opportunities, as new roles emerged in urban areas, from music deejays to local NAACP leaders. In these new spaces, these teens would join the Youth NAACP and the Congress of Racial Equality and some would later form the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. The freedom they wanted was both American and worldwide. They saw themselves in the Cuba Revolution and the African liberation movements. The tension these future Cats would create was based on their refusal to be held within the ideas of American democracy. Instead, they sided with the colored oppressed around the world. During their coming of age, clashes of democracy, capitalism, racism were normal. (Back then, Americans embraced labels, not rejected them; they had no problem being categorized—unless you were called a Communist, of course!) Educated at least through high school and molded by training in reading, writing and speaking, language meant the world to them—and they could see a world language of freedom coming! And it is language that they used well when taking advantage of the expanding American news mediums, particularly local and national broadcasting. Freedom, on the other hand, would become steadily painful as they grew older, less Ralph Ellison-ish invisible and more active.

Other than Malcolm X, their revolutionary father was philosopher Fanon. From the Fanonian worldview, the world was divided by the colonists and the colonized—part of contemporary history and contemporary social reality. Party and Black Power leaders felt Fanon because they saw themselves as victims of colonialism—members of a colony. So they took up arms in both an anti-colonial way and one based on their lived experience. One of Robin D.G. Kelley’s central ideas in his classic book Freedom Dreams is that theory is both academically constructed and from the ground: perhaps Fanon the epitome of this.

The key to Fanon is the contemporary and historic nature of it; it’s simultaneously too radical and too dated. He is creating, using and forging tools at his disposal for his present, an ever-renewing now since 1945. Eventually, Fanon would link Algeria, his intellectual base, to the rest of Africa. He dies in 1961, two years before W.E. B. Du Bois. In many ways, he had succeeded the senior scholar at his most polemical—Fanon’s “Look, a Negro!” is identical, a reverberation of some of Du Bois’s work. Only near their deaths did both begin to see their ideas being spread throughout the world for revolutions real and symbolic. They sought to turn the question mark of being a problem into an exclamation point, to make the Black toy explode in the hands of the white child-like male. The sociologist and the psychiatrist.

Fanon is BC/AD, a Black Knight’s sword cleaving the century in half, like LeRoi Jones’s/Amiri Baraka’s fiery play The Dutchman. He opened a door for the revolutionaries of the Black world to walk through. Algerians, Indochina, Cubans, The Kenyan Land and Freedom Army (a.k.a. the Mau-Mau)…. Fanon, reflecting the non-nonviolent, decolonizing optimism of the times, is the mirror, providing pure, unapologetic, unqualified validation. Since 1945, people around the world slowly attempted to become the heroes they needed and wanted. Time met significance and, individually and collectively, maps of the Pan-African revolution and imagined African-American revolution were drawn.

Freedom, power, voice, jacket, beret, gun. This was noir teenage rebellion against their Great White Fathers. Risk, shock, direct confrontation with armed authority in the eyeball. All that suit-and-tie, hat-in-hand, respectability-politics, we-wear-the-mask minstrel show was gone. Like bebop’s cool rebellion against corny swing, or like rock-‘n’-roll’s noisy rebellion against the jazz’s quintet’s sophistication. A new youth club had been formed, but with spears replacing mouse ears. Impatient. Relentless. Surging. Styles were invented, personas with a new hipness created, a new tone and tenor established—a kind of performance, perhaps a self-confidence easily spilling over into arrogance. It’s not accidental that jazzmen referred to each other as cats. Go, man, go! What was understood and believed by these young Americans who were simultaneously citizens of the new United Nations was an unspoken creed, the key to any success: a willingness to die and the strength to break free from any boundaries. Being Americans, they did not know that they would unleash internal forces bent on their complete destruction.

One of my bosses during my bookish 1990s, the Reverend Benjamin F. Chavis Jr., a former political prisoner himself (the public would call the group of activists framed for firebombing a Wilmington, North Carolina grocery in 1971 “The Wilmington Ten”), would summarize this conflict of values in a book I would own decades later—Psalms from Prison. Along with Abu-Jamal’s First Amendment struggles and the trouble Robben Island inmate Mandela had in smuggling a draft of his autobiography out of prison, Chavis’ grapple to tell his truths altered my personal definition of what success as a Black writer meant:

Our (The Wilmington Ten’s) imprisonment in various county jails and state prisons in 1972 and later from 1976 to 1979 provided the setting for considerable contemplation of the vital questions of justice, human rights, and freedom. We were able to observe firsthand the institutionalization of racism and exploitation behind prison walls. The fact that our innocence of the false charges only made us more determined to fight for freedom. No one could have imagined that it would take millions of dollars and nearly a decade of struggle to win a victory in The Wilmington Ten case. But one thing was clear from the first day of confinement: We had to keep the faith in our God, our people, and our people’s collective will and yearning to be free.

I became increasingly conscious of the importance of trying to document as much of the experience of prison as possible. The prison cell became a place to do theology as a critical function of the ongoing freedom movement. In other words, I wanted to strive to extract from that experience whatever lessons were possible for future theory and practice. Throughout my imprisonment, I managed to record in writing most of my theological and ethical reflections. These were expressed in several literary forms: prayers, laments, meditations, exaltations, critical interrogations, poetry, prophetic prose, doxology, and liturgy.

There were numerous attempts by prison authorities to confiscate and destroy my writings, so I wrote cryptically on toilet tissue and paper napkins, and sometimes I wrote prayers on the bottom of the plastic cover of the bed mattress that I slept on. During visiting hours or through the mail I would send the writings to my home in Oxford, North Carolina. At other times, fellow prisoners would hide the writings wherever they could find a safe place.

Prison was not a place of rehabilitation, particularly if you were political, wrote current political prisoner Russell “Maroon” Shoatz in 2013 in Maroon the Implacable: The Collected Writings of Russell Maroon Shoatz: activist prisoners had no access to typewriters or computers and prison officials consistently attempted to “strip us of most of our reading and of written material—leaving us to the ravages of commercial TV and radio, if that!

“[A]round the same time,” he continued, “we were able to gain the aid of a few small collectives of younger activists, and a still fighting old-timer or two, who took on the task of transcribing our writings, putting them in pamphlets (zines), and making them available—free of charge—through the mail.” Also, Shoatz wrote, there was a newsletter for political prisoners across the country called This Just In. The Inside Story. Mandela, Mumia, Maroon.

My tangential reading of these reference books and other works kept pattern-ing that the Panthers and other radicals demanded to be viewed as self-defending, sexually empowered grown-ass men, not children who are wards of the state. This is why they had to die or be locked away from the physical community and much of human, day-to-day memory. “History is always unkind to those who really make revolutions,” argued H. Rap Brown in his autobiography Die, Nigger, Die!

At their best, these are people who were unafraid to define themselves and their values and, as a result of that level of reckless courage, uncompromisingly confronted the nation in the most public way possible. They were revolutionaries who thought like the Americans they were: they had used their own names, they had registered handguns/rifles and publicly-accessible headquarters with listed phone numbers in cities around the nation. That level of personal and collective transparency in a country determined to perpetually live in its own white-supremacy fantasy construction creates and nourishes constant and vicious attacks. So within the American character, that meant no option of restraint was off the table—any counterrevolutionary tactic was allowed, ranging from public ostracization to outright assassination.

Black youth must learn that if they want to be revolutionaries, spat the infamous FBI memo, they will be dead ones. Or, director J. Edgar Hoover could have added, locked in prison for almost half a century. After the FBI-encouraged bloodshed of 1969, Black youth got the message and moved on down the Soul Train line to a new decade filled with images of rebellion, such as Blaxploitation Afro pics and karate kicks. Two decades later, these reference books remained as invisible and undiscussed in the 1990s as its subjects did—at least prior to the mass movements that decade around Abu-Jamal, Pratt and the Puerto Rican political prisoners (the latter eventually “freed” by Clinton). Discovering and reading this almost-banned literature of the guilty and/or framed, then, is like entering into intellectual dungeons of knowledge, ready to hear the tales from the crypts kept there, but being surrounded by torture chambers designed to create and reinforce amnesia.

HISTORIC VICTORIES, FOR OBVIOUS reasons, were missing from the reference books. Triumphs such as the 1971 exoneration of the Panther 21. The group is absent because most of its members freed themselves, and did so while they were still young. PM Press thought about the age and significance of the Panther 21 and a largely-forgotten book they created. So they compiled Look For Me in the Whirlwind: From The Panther 21 to 21st Century Revolutions, updating and repurposing for 2017 a Black radical literary work I had never heard of: The Collective Autobiography of the Panther 21. The core 21 book—a ’70-’71 oral-history product, pretty much written and edited in real, seized time—needed to be added to the 21th-century mix to see what memories it would bring forth into the merged Floyd Memorial Day.

One Panther story that I saw that had been told twice was Jamal Josephs’. In the Panther 21 anthology, the 18-year-old sounded like a typical urban Panther, talking about his street life before the Party: “What I was doing was committing what I now recognize as reactionary suicide,” using Party co-founder Huey P. Newton’s term. “The conditions had become so intense in the neighborhood in terms of what was happening to other people, what was happening to friends: they were getting busted, and getting killed, in this life-and-death struggle that niggers get in with one another. Instead of trying to combat this, instead of trying to do something to stop this, I just submitted to the conditions. If certain things hadn’t happened to me a little later on, I would have died at the hands of these conditions. Died a reactionary death, you know. Died by being submissive, not trying to change any of this….”

“When I was around thirteen it was the era of the birth of cries for Black Power. I was wearing dashikis and an Afro, and I was running around saying ‘Black Power’ one minute and getting off into a nigger-kill-nigger bag the next….” Then, in October of 1968, Jamal joined the Party. The tenth grader had read The Autobiography of Malcolm X, had heard H. Rap Brown speak, and had been part of a young Black cultural club. At first, he thought the Party “was a totally suicidal movement.” Then he saw the bold berets on television in Sacramento. “I said, wow, those niggers are crazy.’…It seemed like the only fate they had was death, because of the type of things they were doing.” The Panthers represented: Love, world dreaming, style, resilience, experimental disposition, fire, pride, audacity, cool, collaboration, velocity and, perhaps most importantly, energy. The group had a pent-up excitement and physicality no one—including Jamal and perhaps even the Panthers themselves—was prepared to handle.

Joseph’s second telling of his Cat tale was in his 2012 memoir, Panther Baby: A Life of Rebellion and Reinvention. “I walked into a Panther office in Brooklyn in September 1968,” and was given a new, non-slave moniker by a brother who made it up on the spot—”Unbutu Usa Jamal. It means ‘he who comes together in the spirit of Blackness.’ I would find out later that James was pulling syllables and meanings out of the air, but at that moment, I had been reborn and renamed”—and became the youngest member of the Panther 21.

He endured all of the tortures of prison that all Panthers tell, and then, like the rest of the 21, got out—on his 21st birthday. With the exception of slight additions to street life, alcohol and coke, the rest sounds eerily similar to Abu-Jamal’s pre-prison life in the Philly ‘70s: “I took classes at Brooklyn College, worked various jobs and used a student loan to buy a gypsy cab. I taught karate classes in Harlem, the Lower East Side and Brooklyn…I hung out with an eclectic group that included street people, artists and folks from the nightlife.”

But it was The Man’s Tricknology and not The Life that returned him to jail in 1981. He and his wife Joyce wound up acting out a less-deadly version of the Chicago police raid on the city’s Black Panther headquarters 12 years before, which led to the murder of Panthers Fred Hampton and Mark Clark. “The FBI kicked our door in at four in the morning,” Jamal wrote. “Agents dragged me from the bedroom while a two-hundred-pound agent sat on Joyce’s back and pointed an M-16 at her head. ‘Get off me, I’m pregnant!’ I heard her angrily yell. I fought to get to her but I was cuffed and dragged from the apartment.”

He was tried in federal court. Joyce and Jamal Jr. were in the courtroom when Jamal was convicted of harboring Mutulu Shakur—who, along with members of the BLA and a white revolutionary group, the Weather Underground, robbed a Brinks armored car. Jamal remained consistent and loyal and that came with serious consequences. “I was now 29 years old, back in prison after eight years of posttraumatic stress blues. My wild post-Panther ride had led from the streets, nightlife and theater back to revolutionary comrades living underground.” He did five-and-a-half at Leavenworth State Penitentiary in Kansas. The personal university he forged within birthed a playwright.

I’ve never met Joseph, but I was in the same room with him once—a New York City movie theater in 2017, where he was screening Chapter and Verse, his feature film. I guess Joseph would wince and give me the side-eye if I said his film was (just) Boyz ‘n’ the Hood for the Millennial generation, starring a new-jack Socrates Fortlow, the hero of Walter Mosley’s novel Always Outnumbered, Always Outgunned. But that’s what the film was, and there is nothing wrong with that. Joseph seemed to have wanted the entire Black community to be his audience, so he had something for everyone: for youngsters who crave ‘Hood violence; older people who will identify with Loretta Devine, who anchors this film; images of historic Black leaders in the background (are they sad angels, witnessing the 21st century Black dysfunction?) for the “conscious” filmgoer who knows he’s watching a film about Harlem done by a former NYC Panther. It was the sum of its post-Trayvon Martin and pre-George Floyd parts, no more and no less, and ambitious only in its chief theme: that the survival of the many takes real planning and real sacrifice by the few. But that February, when I saw it, mass, sustained radicalism still remained in the American background, as it does in the film.

When you live most of your life on the outside, revolutionary love—and the pure optimism and audacity it creates—can last only so long.

WITH ONE MAJOR EXCEPTION, my personal experience with political prisoners has been very fleeting. I saw, but did not get a chance meet, Odinga around 2016 when Nkechi Taifa, a Black lawyer who is a mainstay of the D.C. Black activist community, hosted him at her home to celebrate his release. I sent Abu-Jamal a letter in the early ‘00s asking if I could interview him for my MAJ biography project, and he sent me a very beautifully written no. I spent the better part of a 2015 afternoon with “Marshall” Eddie Conway at The Real News Network in Baltimore, enjoying that this man who had been through so much pain in his long life now had a slick-looking glass office and an assistant, like any other high-profile network television correspondent!

But the only story I can really claim to share with a political prisoner—albeit a historic one, from at least a decade before I entered into consciousness—is a true-life political adventure right before Abu-Jamal was fully live from death row. The former political prisoner I came to knew the best—one for whom I worked for—was another victory too successful to be mentioned in the guides. While many educated Blacks in the ’70s were buying into the system and becoming first “Afro-Americans” and then Black Americans, Ben Chavis spent almost the entire decade in prison as a member of The Wilmington Ten. All of the accused were acquitted in 1980. Chavis and the rest of the Ten collectively had become an international cause-celebre (he was mentioned as one of the Movement’s next priorities on the last page of Angela Davis’ 1974 Autobiography) and were living proof that political prisoners existed in liberal-democracy America.

My front-row seat with him happened between the ’93-’94 academic year. In Baltimore, I was near the center of a great political experiment—the Baby Boomer Black radical movement’s takeover of a major Civil Rights organization. I got to see Chavis’ style close-up, and it taught me the heartbreaking romance of radicalism and how that romance must not replace discipline.