By Todd Steven Burroughs

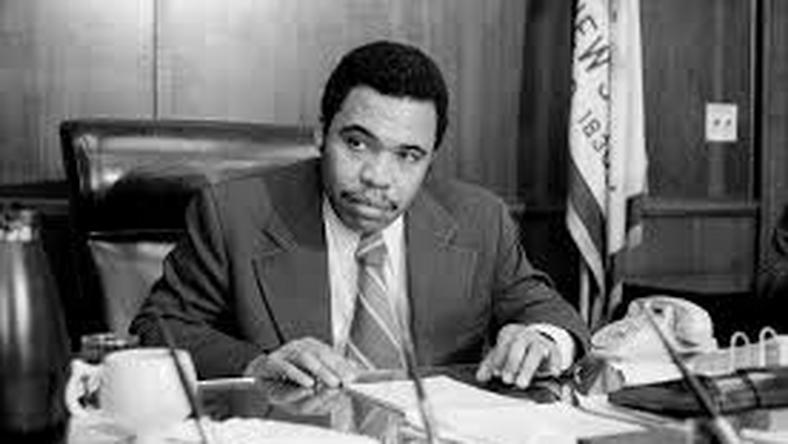

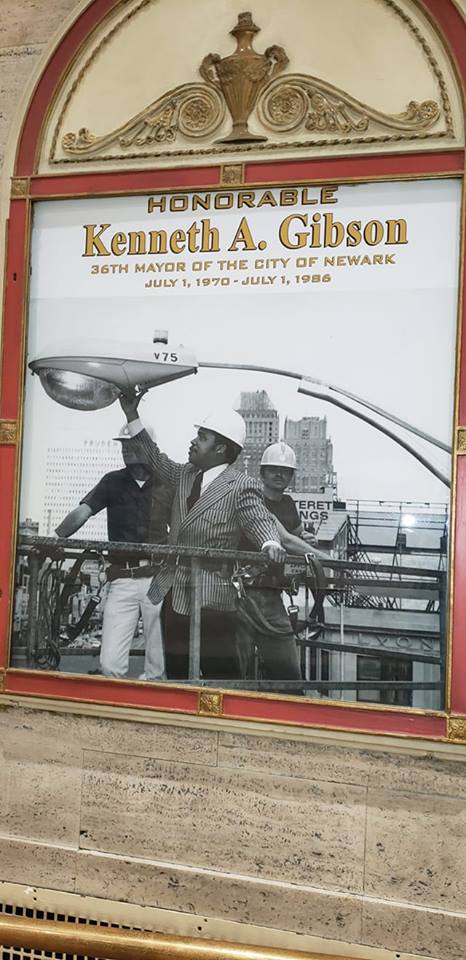

NEWARK SYMPHONY HALL was, at best, half full Thursday night for the funeral of Kenneth Gibson, whose full surname will always be Newark’s first African-American mayor and the first Black mayor of a major northeastern city. It was packed for Amiri Baraka, but that was five years ago. Cinco years is a long time for aging ‘60s folks.

Ras Baraka would know. The current mayor had eulogized his father in this very space, and was now one of the many to give tribute to the man his father helped put in office. Gibson was “our Carl Stokes, our Richard Hatcher, our Maynard Jackson,” and on and on, he roll-called in a poem-ish speech. He announced that Broad Street, a central downtown artery, has been co-named for Gibson. Baraka—who mentioned the photo his family found of him at four-years-old in the mayor’s arms, one that quickly went viral in the last week—was bookended by two standing ovations because he is also the child of all of these former Black Power activists: Rev. Ralph T. Grant, a former member of the Newark City Council and the night’s host, called Mayor Baraka “the son of thunder,” which had this writer think of Shango as well as Imamu Amiri Baraka. Vintage Newark: devout Black Christianity merges, sometimes subtly, sometimes not, with African mythos and states of being.

If someone was new to Newark, he or she wouldn’t know that Gibson had serious squabbles with some of those who came to praise and bury him. Former Newark Mayor Sharpe James, who ousted Gibson in a tough 1986 campaign: “He was the man who could bring the city together” after the 1967 rebellion. Activist Lawrence Hamm, who Gibson named to the Newark Board of Education at the age of 17 in 1971 and publicly regretted it two years later when Hamm became a Black nationalist: “You wouldn’t know my name if it wasn’t for Ken Gibson.” (The activist said he didn’t speak to Gibson for 35 years after Gibson failed to reappoint him, but eventually reconciled, and reminisced about his joy of seeing Gibson and his wife Camille at a Newark 1967 rebellion commemoration in 2009, sponsored by Hamm’s activist group, the People’s Organization for Progress.) Hamm literally came in from the cold, where POP had just finished marching and commemorating the King assassination. Gibson, he said, was a symbol of the Black Power movement the way King was of the Civil Rights movement. “He found me protesting (in 1971, as a high school student activist), and he leaves me protesting.”

New Jersey Lt. Gov. Shelia Oliver, a Newark native who is a resident of nearby East Orange, wanted to remind the audience how dangerous it was for Gibson to even run for mayor, which he did unsuccessfully in 1966 before his historic victory. The United Brothers slate, formed by Amiri Baraka and his Committee for a Unified Newark, was “called everything you could imagine” and was “under the threat of death.” (A serious statement to say, particularly when one realizes that the Mafia directly controlled the city.) A former City Hall staffer under Gibson, she roll-called all of Newark’s civic leaders who would have filled Symphony Hall if they had not gone first. She gave Camille a blown-up photo of Baby Baraka and Gibson.

The Rev. Dr. DeForest B. Soaries Jr. was one of those Black nationalist college students who the elder Baraka recruited around the nation to make Newark a Black Power city (“the land needed to change hands”) in 1970. Those dedicated Black college activists dodged roaches and rats as they slept on the floors at Scudder Homes, a city housing project, because Newark had, in 1970, become the foci of the Black Power movement, the center of Black radical motion.

Gibson asked permission of the Black and Puerto Rican community, not the white power structure, to represent them in 1966 and in 1970, remembered Soaries. Gibson, he declared, “wasn’t great because he was famous, he was famous because he was great.” And, as she and Oliver both said, he paid his debt to young Black people as mayor by setting up a pipeline to HBCUs like Shaw and Grambling universities.

Positive memories always rule at a funeral, but culturally Black events in Newark are dominated by them. Gibson needed to be seen through red-black-and-green glasses, because it obscured the complex reality that followed the 1970 street celebrations on the street that now has his name.

WHAT IS IT about April 4th? Martin Luther King and Adam Clayton Powell both died on that day—the former by an assassin’s bullet, the latter by prostate disease. Maya Angelou was born. As was Hugh Masakela, who, on his 80th celebration of his birth, got a Google Doodle, in 2019 the ultimate in subtle world acknowledgement. The Power of Two Fours. Place a figure eight—two connected zeroes—on its side and get a representation of infinity, but place two fours together and get only the memories that arise from within. External versus internal.

So this month, more than most, feels like a fill-in between February’s Black History/African Heritage Month and the summer Black convention season. The Rev. Al Sharpton’s National Action Network met in New York this week. The Institute of the Black World-21st Century is meeting in Newark Friday night. The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture had an event honoring Sonia Sanchez. These headline gatherings, as usual, obscure the smaller meets.

The snow has melted by April, leaving land that has to be cultivated. The whiteness is no longer the obstacle, because it turns mushy, then clear before it gets absorbed by the ground. The sun appears, promising summer’s warmth. For Black people, the goal is always to make the white disappear, or, at least, managed. The People of the Sun are always waiting for that break, looking forward even to the rain as an alternative. Gibson’s viewing day, right before the funeral in the rotunda of his City Hall, was filled with sunshine.

IF HAMM IS right about Kenneth Gibson being a Black Power symbol, he was a reluctant one. With his short hair and cuffed pants (Jesse Jackson famously made fun of him, on air, at an Operation Breadbasket meeting endorsing him and pledging himself to Gibson’s 1970 mayoral campaign), Gibson, sadly, wanted to be mayor of all of the people. Black people, who voted for Gibson to get rid of what Hamm called “the apartheid system we had lived in for so long,” were beginning to understand what that meant.

When Hamm (who took the name Adhimu Changa—Kiswhahili for “Exalted Youth,” one Amiri Baraka gave him) pushed for, and got passed, an ordinance that allowed for the Black Nationalist flag to fly in any Newark public school with a Black population of more than 50 percent, Gibson told The New York Times in 1973 that his worst mistake as mayor was Hamm’s appointment. When Baraka’s Congress of African People wanted to build a housing development, Kawaida Towers, they were stymied by not only Gibson, but a Black City Council President, Earl Harris. Amiri Baraka denigrated the two as shills for the city’s downtown interests—which, in Newark terms, still meant literally the Mafia. Gibson and Harris attempted to keep the peace while a small portion of the city’s Italians still wielded clubs. Pragmatism betrayed revolution, the first of many throughout Black America’s early 1970s.

Gibson did real, practical things, like a trained engineer would. He reduced the child mortality rate, speakers reminded folks Thursday night. There was a determination to make him fit into a Black Power vibe that just wasn’t him. He not only wasn’t like Malcolm, he wasn’t even like Jesse Jackson. But he was the kind of man who, as James recalled, personally introduced him to the U.S. Conference of Mayors—a group Gibson had become the first Black president of–after James defeated him. Gibson knew his lane. “I’m not a manager of hope, I’m a manager of resources,” he once told The New York Times. And that management, Oliver reminded the audience, allowed Newark to have, for the first time, a large group of Black middle-class people.

1 min ·

I WENT TO the Honorable Mayor Kenneth Gibson’s funeral last night with my cousin Mary and I must say I am glad that I went. I was impressed with every message by every speaker that reminisced on their experiences with Mayor Gibson. Current Mayor @rasjbaraka who speaks as if he is delivering a poem in these settings, something I can appreciate and I am very familiar with. Former Mayor Sharpe James whom, despite how you feel about him, ALWAYS is insightful about the history of Newark, Larry Hamm who embodies passion every time that he speaks, Lt. Governor Shelia Oliver who has ALWAYS been a very down to earth and personable soul who has given me some life changing advice more than once and my friend and brother, Mayor Gibson’s Grandson Mtima Taifa, whom despite getting emotional, toiled through a beautiful message about his Grandfather…THE MAN outside being the Mayor.

The first time I met the Mayor was when I was in grade school as a student at St. Rose of Lima and the reason why I never forgot it is because there was an older student who seemed to have issue with the fact that I appeared mesmerized to meet Newark’s first Black Mayor and the first Black Mayor of a major city. Shit still bothers me to this day. Maybe because he had seen him before, or a few times but whatever the case, why are you killing my vibe because I appreciated shaking this man’s hand? Whatever the case, I always remembered that because those were good times for me and an inspiration to winning the position of President EVERY YEAR as a student at St. Rose of Lima, despite the odds!

Mayor Gibson was the stepping stone for us to build on our legacy but he also should be respected because of the tumultuous environment in the early 70’s he endured.

May the Ancestors be pleased… (Ibaye)

THE WAY THURSDAY night’s former mayors, and other speakers, chronologized the Black Power Newark story of Gibson to the present was quite fascinating. More than one speaker said:

Gibson, who died at 86, was the pioneer.

Sharpe James, now 83, set the foundation.

Baraka, who turns 49 next week, has each foot on a shoulder of the two, reaching upward, moving forward.

“Ken had to tear them down (Newark’s dilapidated housing),” preached Grant. “So that Sharpe could build them up. So that Baraka would put the finishing touches on it.”

(Because of non-mayor Baraka there came) Gibson-Sharpe-Baraka. But there was a Newark mayor prominently missing in the roll call, and not just onetime-mayoral-sub and current City Councilor Louis Quintana, who was Newark’s first Latino mayor in 2013-2014. The young-ish man (he turns 50 this month) who left the mayor’s chair for the U.S. Senate, the one who Quintana replaced, was not mentioned—not in the program, not by any of the speakers. No(t) representative. Two-sided amnesia. Silenced out of oral history.

To the aging Black Power-ites, the wannabe president just doesn’t fit into their story. Thursday night, Cory was Casper—the friendly ghost in the hall no one missed, or wanted to acknowledge, at least not while this writer was there. He was quoted today by an esteemed local columnist as another shoulder-stander. (April 12th update: I found out Booker’s tribute came earlier at City Hall, where Gibson’s body lay in state.) Booker clearly stands alone, outside.

AS THIS IS being thought and written, IBW21 is in Newark is preparing to talk Friday night about gentrification, a less and less subtle form of recolonization.

Masekela’s birthday was Thursday, but his historic earworm remains.

Everything must change

(Everything must change)

Everything must change

(Nothing is forever)

What is it that makes a person wanna stay in power forever?

What is the reason for a man to wanna force his will upon a lot?

Jonasi Savimbi why don’t you get away from here

Heyyy Charlie Taylor why don’t you get away from here

Arap Moi when are you gonna say goodbye

Hey Robert Mugabe don’t you think it’s time to say goodbye

Mandela he showed us the way

Nyerere finally went away

Masire also called it a day

Chiluba the people chased him away

When will the others say goodbye

Mobutu he destroyed

the Congo

Eyadema is the owner of Togo

Obote and Amin destroyed Uganda

Mugabe refuses to go (to go)

When will they stop

all the wars

In Sudan and Somali people are dying in the war

In Rwanda and Burundi people are dying in the war

In the Congo and Angola millions are dying in the war

In Sierra Leone people are dying in the war

In Liberia and Guinea people are dying in the war

Why don’t we put our heads together and find the cure for all diseases

Why don’t we put our heads together to fight the AIDS and poverty

All the wealthy

countries say they wanna stop the wars in Africa

If they want peace so badly why don’t they stop selling us arms

Time, incidentally the name of the 2002 album that contains the above song, has this way of halting solo dynasties, of making the paint of any individual portrait eventually flake. Masekela, who entered the Realm of the Ancestors early last year, can now argue personally with almost all of the African leaders he attempted to cancel above. But the dark, poor people are still dying in the war around the world, including on the Brick City streets, as the third decade of the new century speedily approaches. Fifty years after the Revolution, apathy and unemployment are still high. Booker coming back to town dressed as Captain America is not changing that. Powell famously asked, “What’s in your hand?” The Presidential candidate better put in his a large version of that shield—the sphere that’s always on the rebound, the one that reaps what is sown.

Back inside Symphony Hall, a place Gibson made sure was listed as a historic landmark, the live-action black-and/versus-white photo album once again closed, and Newark’s history hula-hoop—its circle of suspended time—was again placed on an African ethereal shelf. Downtown now has a new street name, seen through 2020 eyes, a symbol for those who remember, who choose to pass on the story. (Which will include, as someone not from the era will whisper in polite company, that Gibson and James, like the African leaders Masekela sung about, both stayed in office waaayyy too long and, ultimately, got caught in corruption’s mire—as did even Grant, Thursday night’s host. Not that Blacks from those times would ever publicly care.) But undeniably, the red-black-and-green era of the city is fading, one major death at a time. Newark’s mid-century American Maroon story of northern, urban, dashiki-ed-and-poetry-ed resistance will not be over until the city’s last pre-Boomer and Boomer fall. By the time Rev. Soaries eulogized in the keynote slot, the hall was only a quarter-full. For the coming gentrifiers, it was still early, but for 20th century Newark, it was getting late.

-30-

Todd Steven Burroughs, Ph.D., is an independent researcher and writer based in Newark, N.J. He is the author of Warrior Princess: A People’s Biography of Ida B. Wells, and Marvel’s Black Panther: A Comic Book Biography, From Stan Lee to Ta-Nehisi Coates, both published by Diasporic Africa Press. His 2014 audiobook, Son-Shine On Cracked Sidewalks, deals with the first mayoral election of Ras Baraka, the son of the late activist and writer Amiri Baraka, in Newark.

Humbled that so many appreciated me reminiscing down memory lane about my recollection of the Honorable Mayor Kenneth Gibson.

Thanx forbsharing Dr. Burroughs, you are a gentleman and a scholar.

Beautiful, Searing, Sensitive piece, Brother Dr. Todd. Thank you, Thank you, Thank you.