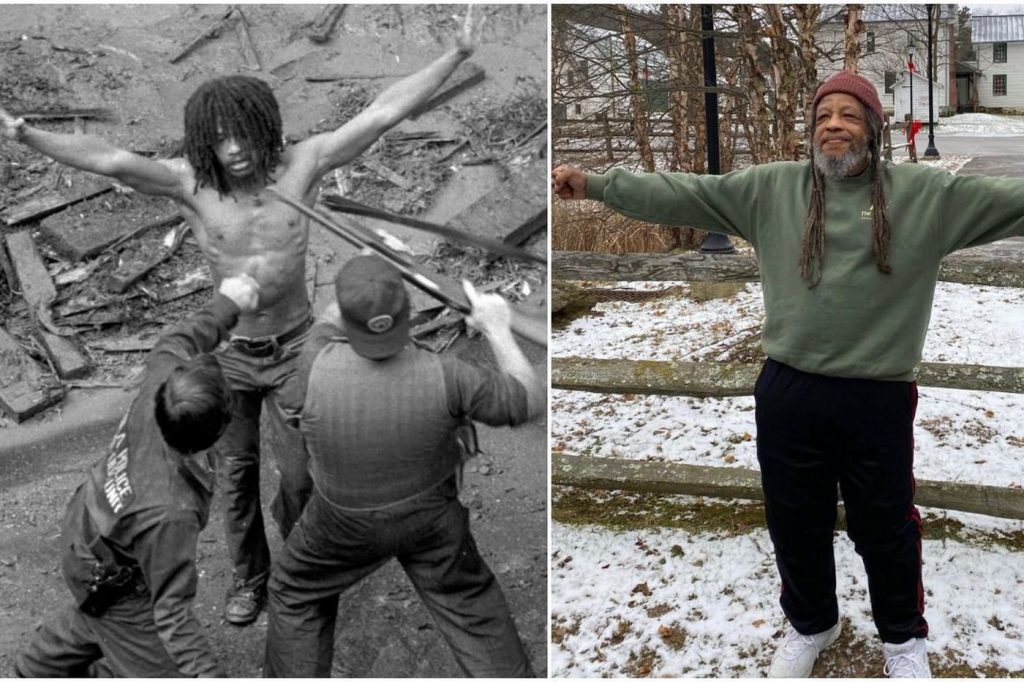

The harassment of radical senior citizen Mumia Abu-Jamal continues, even during a pandemic. It’s not enough that’s he’s been in jail for almost 40 years (he turns 66 on April 24). Now Pennsylvania prison authorities–the world’s sorest-winner champions–cruelly lied that he was ill, possibly with COVID.

By Todd Steven Burroughs

Death’s shadow can replicate over the decades, emerging from the depths of time and space to scare at any time. Not the time for a belated April Fool’s joke. Unless you’re a guard or official at SCI Mahanoy, where the most famous prisoner in the world not named Julian Assange is housed. All day long on April 15, the prison received calls from Mumia Abu-Jamal supporters in a day of action. The supporters were, and are, correctly concerned that the world-renowned author and historian—now a senior citizen with pre-existing conditions, including cirrhosis of the liver, which he got after being misdiagnosed in 2015—would be, along with other elderly political prisoners and elderly prisoners overall, in fatal danger from COVID-19.

After a long day of having to deal with public outrage over somebody in jail for decades after such a questionable trial, somebody at SCI Mahanoy thought it’d be funny to scare the “Free Mumia” folks. So when Santiago Alverez, a 22-year-old University of California at Santa Cruz student and Abu-Jamal supporter, got a text from somebody who had made her voice heard, he jumped into action. His friend said somebody at Mahanoy told her that Abu-Jamal was ill and in an ambulance, on his way to a Scranton, Pennsylvania hospital. Did he have COVID? Um, maybe.

Alverez called Mahanoy, and recorded the two different exchanges: one with “Phillip Howard,” the second with “Darryl Miller”:

Funny, huh? Especially in a pandemic that disproportionally affects prisoners.

It shook the activists to the core, and their fear and panic turned to relief after a brief phone conversation with Abu-Jamal. Then relief morphed into the most righteous rage. Johanna Fernandez, who led the campaign to save the imprisoned writer from death by medical neglect in 2015, told everyone on Facebook the bad news before they found out that Abu-Jamal was fine and in his cell the whole time. She was not pleased Thursday, at a Zoom press conference denouncing the officials at Mahanoy and prepping the “Free Mumia” movement for a weekend of events in Philadelphia celebrating Abu-Jamal’s 66th birthday. She put out the erroneous news on Wednesday because, as she said, “never in my life,” even understanding how anti-Mumia activists can act like “warped, white supremacists,” could she expect state officials to act as they did. Suzanne Ross, another longtime Abu-Jamal supporter, said the prank was the state’s “fantasy” come forth: it had failed to kill Abu-Jamal in 1995, in 1999 and in 2015, so this is all it had left.

Fernandez talked about how she just buried her own uncle from COVID, so this was not the time for putting up with any racist foolishness, since Black and brown people are twice as likely to die from the virus than whites and that prisons were about to become the new virus epicenter.

She and the other activists on the Zoom call—Ross and, among others, Marc Lamont Hill (who, after hearing the calls, characterized as “stunning” the “level of cruelty” behind the exchange)—called for the firing of that prison official and the immediate freedom of all elderly and nonviolent prisoners, especially America’s political prisoners such as Abu-Jamal. “We will not allow the state of Pennsylvania and the United States to allow our prisoners to die like dogs, like animals, in American prisoners,” declared Fernandez, defiance etched into her face. “We’re in a moment of extreme crisis,” Hill confirmed.

Perhaps the most ironic moment of the press conference was hearing from Delbert Africa, recently released member of the MOVE 9—a group the twenty-something Abu-Jamal, then a Philadelphia radio reporter, interviewed from jail back between 1979 and 1981. Africa said that the same “nasty” stunt was pulled on him when he was an inmate.

Fernandez’s fury brought forth a memory, from December 2015. Note how in America, there are two sides as to how/if someone gets health care:

JARED BALL, PRODUCER, The Real News Network: Welcome, everyone, back to the Real News Network. I’m Jared Ball here in Baltimore.

Longtime political prisoner, journalist, and author Mumia Abu-Jamal testified in a Scranton, Pennsylvania courtroom via webcam last week that Hepatitis C medication he needed had been denied him by prison officials because they say he is too healthy to receive treatment. Supporters in his legal team are continuing this week to make the case for Abu-Jamal that he be given drugs he himself testified might save his life. Without them, he said, I will die.

To discuss this and more is Dr. Johanna Fernandez, who teaches in the Black and Latino Studies Department at Baruch College, is a veteran political prisoner rights activist and editor of Mumia Abu-Jamal’s latest collection of essays, Writing On The Wall. Welcome back to the Real News, Dr. Fernandez.

JOHANNA FERNANDEZ: Thank you very much, Dr. Ball, for having me on your show.

BALL: So please, just tell us, what is the latest regarding Mumia’s health, and latest efforts to attain proper medical care for him?

FERNANDEZ: Well, Mumia has definitely shown improvement from the crisis into which he fell in March of this year, on March 30, 2015. His skin condition, however, after what his doctor said was all of the medication that can possibly be given a prisoner, after all of that his skin condition is still with him. And he continues to scratch a lot, and that’s important because apparently scratching is, is one of the symptoms of patients with Hepatitis C, with active Hepatitis C. And that was one of the issues that was thoroughly discussed in the courtroom, both last Friday and yesterday.

BALL: So what is being argued this week, still? What are the two sides arguing, and what particularly are prison officials or the state saying is the reason that he is apparently too healthy? I mean, the reports over the last few months of Mumia’s health, as you said, deteriorating were pretty stark. It’s amazing that someone could actually argue he’s too healthy to receive this medication.

FERNANDEZ: Right. So I think it’s important to note that the judge who’s hearing this case, Judge Mariani, prefaced the proceedings by saying, after he quoted from the report submitted to the court by Mumia Abu-Jamal himself, that the problem before us is “serious”, quote-unquote. And that really set the tone for the proceedings. Our side is arguing that Mumia has active Hepatitis C, and that he should immediately be treated with the medication available on the market, which has a 95 percent cure rate. The opposing side, immediately after the judge presented the case, suggested that the case should not be heard by him, and that it should be immediately thrown out, because according to them Mumia did not exhaust his administrative appeals before he proceeded into the court. That was a position that was struck down after over two hours of argumentation on both sides. The judge presented a formal position that Mumia had done everything he needed to do within the law to proceed to the court.

I say this because the opposing side essentially did not want to hear the details of the crisis. They wanted to dismiss the case on a technicality. And that led the judge to ask the opposing attorneys whether in fact they wanted to proceed in the court by making arguments that were attentive to form and not content. Which–in a case involving a prisoner or prisoner like Mumia, and in a case involving the healthcare of prisoners generally, that is, that is really important. The judge has suggested that he is concerned about content and the gravity of the matter.

So yesterday, our doctor, Dr. Joe Harris, essentially argued according to his expertise that in Mumia’s case, because he has developed significant fibrosis, which is scarring of the liver, that suggests that he has active Hepatitis C that will continue to devour his liver if he is not given the treatment he needs. So that’s what our side argued. And the other side essentially suggested that Mumia is not sick enough to receive these medications.

BALL: So let me just ask very quickly, as we will continue to follow this and I know you all will be wrapping this up this week. But there are those who have argued and continue to argue that this is just the state’s end run around Mumia being taken off death row last year, in looking for another way to execute this longtime political prisoner. How do you respond to those who take that perspective of this?

FERNANDEZ: Well, I think it’s a little complicated. I think that once again, Mumia is at the cutting edge of an issue that concerns thousands of prisoners in Pennsylvania, and in the nation. In the 1990s, as you know, he became the face of the movement against the death penalty, and we stopped his execution. But now the issue, as he’s aged in prison, is illness. And I think that the reason why the state of Pennsylvania is hesitant to offer Mumia the treatment he needs, and that has been proven he needs, according to expert witness, is that if they make a decision to treat Mumia with Hepatitis C medication they’re going to have to treat the 10,000 other prisoners with active Hepatitis C in Pennsylvania who have filed a class action suit.

So the issue is really not establishing a precedent that then will force them to take ethical medical action in the cases of so many others.

Now, of course, COVID has put all prisoners, around the world, on medical Death Rows. This was a point made repeatedly Thursday.

The goal of this present moment is, frankly, to make Maureen Faulkner’s nightmare come true. Why did the Faulkner-Fraternal Order of Police side fight so long and hard to stick that poison needle in Abu-Jamal’s arm? Because they wanted to avoid this exact situation, since it was clear that her decades of public battles were not going to produce an execution. For the widow of slain officer Daniel Faulkner, Abu-Jamal has been and always will be a Phantom menace, an evil Ghost Who Walks.

Until 2011, when Abu-Jamal was released to general population, the fact that her side had won since the beginning—that Abu-Jamal was convicted of first-degree murder and on Death Row, a man now decades away from the touch of his wife, children and now grandchildren—was not somehow good enough: with the public anger displayed on their side over the years, it felt that they would only feel victory by urinating on Abu-Jamal’s grave and shutting him up permanently. Since the 1994 National Public Radio controversy and the 1995 publication of Abu-Jamal’s first book, Live From Death Row, they had been publicly incensed by every major “Free Mumia” celebrity event around the nation and the world (but hardly ever in Philadelphia, they never failed to point out)—a benefit rock concert in New Jersey one year, a street naming in France in another. They felt constantly under attack by Abu-Jamal’s supporters and returned that attack in kind, publicly jousting, using their contacts in local media and national conservative outlets to respond to the national positive or “objective” coverage Abu-Jamal, his lawyers and his supporters got.

In 2007, a year after the 25th anniversary of the shooting, she was asked by a reporter if it was just better to allow Abu-Jamal life in prison. It was a hard question for her, because she knew that much of the energy around Abu-Jamal’s “Free Mumia” movement was based almost solely around the death penalty. If you take away the death penalty, the analysis went, he’d just become another radical in jail, permanently away from the headlines until he died in prison.

“This idea was not new,” Faulkner wrote in her 2008 memoir Murdered by Mumia: A Life Sentence of Loss, Pain, and Injustice, an extended jihad against Abu-Jamal and his supporters. “In the past I had often thought of or been asked by friends about the same thing. I had never been asked this question in public, but I knew my answer before the reporter finished the question.” She explained to the reporters the problems with life without parole—that her family and friends would “have to live every day for the rest of our lives knowing that a future governor could set Jamal free with the stroke of a pen, and that I had no doubt that Jamal’s misguided and uninformed supporters and friends would relentlessly lie about the facts to future generations in order to perpetuate the myth that Jamal is the victim of a racist justice system, then demand his release.” She talked about governors who decided to commute sentences out of pity for harmless-looking, sickly old men and did not want that happen to Abu-Jamal—somebody who could one day be viewed as “a person who committed a crime in a bygone day who had been ‘punished enough.’….I told them I wanted to be certain that Jamal could never be free again—that he would die alone in prison away from his family like Danny had died alone on the street on December 9.”

So during this unseen-phantom outbreak, the goal of the protestors during Abu-Jamal’s birthday weekend is to get Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf to temporarily lose his sanity and free Faulkner’s version, who, in newspaper comic strips and comicbooks, is also known as The Man Who Cannot Die. Fantasy and nightmare intertwine as a powerful ghost walks the Earth, threatening to lethally inject all of 2020.

Because of this juxtaposition-connection combo, the near 40-year cycle of abuse hurled at Abu-Jamal for surviving both legal lynchings and medical crises has been consistent. As the election prepares to scrub up and get into medical gear, Gil Scott-Heron left a commentary about yesterday’s voting follies that reminds that “we’ve seen all the reruns before.” Modern calls for prison abolition go back at least to a young Angela Davis, defiant in mini-skirt and Afro as “Soul Train” was leaving the station for the first time, demanding freedom for the Soledad Brothers. The activity around Abu-Jamal’s birthday is an attempt at matching a historic echo in the hopes it will bounce against the walls of the “Free Mumia”’s movement’s life-imprisonment apathy, bounding back to its international heyday–the 1995-era Death Row-with-date-to-die power. If the death penalty was the key to the international energy of the “Free Mumia” movement, goes the 2020 thought, well, what the hell is this situation, then?

The Mahanoy guard or official’s private laughter, dark humor done in the service of Faulkner, the FOP and the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, is the perfect gas to light yet another match. But the movement’s challenge is clear: there’s still not enough kindling, and death—real, not its historical threat from a now-dead Judge Albert Sabo, Abu-Jamal’s 20th-century, perennial enemy—has now struck home too many times in March and April of 2020 for the masses to have the luxury to be focused on the potential problems of a now-famous author, destined to transition into the African literary pantheon, a 20th and 21st century Black radical legend.

So the movement to protect Black bodies is old, as ancient as the first African who rebelled at the actions of the first Arab slave trader. But the entire world has not shuddered like this in a century, in daily fear from an invisible spectre giving out deadly cooties. A world that on New Year’s Day was desiring to be like arrogant Tony Stark is now locked up at Easter, masked like a scaredy-cat Zorro, huddling in vain, imprisoned by the imperceptible whim of a slo-mo Thanos snap.

But the obvious difference between the rest of the world and those in American prisons is that we can unlock the doors when we wish, choose to be next to who we wish. It’s difficult to create unity when proximity can now equal death. It’s new territory when we can’t see loved ones locked away, either in their homes, hospital beds or prison cells. The anger, anguish and terror are new for many of us, particularly the young, but for Abu-Jamal, sadly, they are now old friends that he has known for almost two-thirds of his life.

-30-

Todd Steven Burroughs, Ph.D., is an independent researcher and writer based in Newark, N.J. He has written about Abu-Jamal for 25 years. He is the author of Warrior Princess: A People’s Biography of Ida B. Wells, and Marvel’s Black Panther: A Comic Book Biography, From Stan Lee to Ta-Nehisi Coates, both published by Diasporic Africa Press. His 2014 audiobook, Son-Shine On Cracked Sidewalks, deals with the first mayoral election of Ras Baraka, the son of the late activist and writer Amiri Baraka, in Newark. He is working on a journalistic, and, perhaps now, literary biography of Abu-Jamal.

Just to know that some people would conjure up fake news about Mumia is desperate tactic of destruction. Luckily you can not keep a black an down unlike others. He will leave the iron bars one day, hopefully sooner than later,