“‘I don’t like boxing, but he was a thing apart. His grace was almost appalling.”

— Toni Morrison on Muhammad Ali, in the David Remnick book King of the World

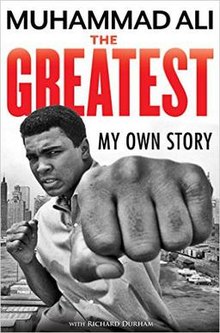

Muhammad Ali, dethroned by the United States of America but still a baadddd dude, was looking for a publisher for his autobiography in 1970. Five years ago, the publication of one from his former mentor and friend, Malcolm X, was slowly morphing from a Black radical mainstay to a mainstream Black American literary keepsake. Ali needed money, and he knew that in the right hands his story could sell almost as much as his fight-night tickets once did. So too believed The Nation of Islam, who had already chosen its and Ali’s equivalent of Alex Haley: a former editor of Muhammad Speaks and radio and TV writer named Richard Durham. Now The Nation, Durham, and Ali needed a powerful publisher. Ali chose Random House. Sonja D. Williams, Durham’s biographer, wrote that Ali was pleased that Random House had a Black editor.

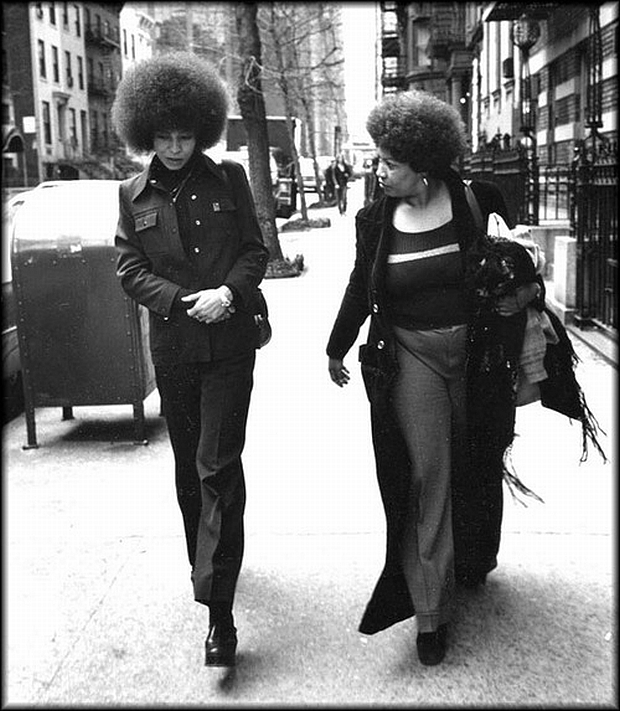

But that editor left. Charles F. Harris left Random House because he got the opportunity to be in charge of the newly-formed Howard University Press. Durham looked wearily at the Black woman replacing Harris on the Ali project: “He’d been in business forever as a journalist and editor, (while) I had published this one book which I don’t think he liked much—The Bluest Eye.” The Nation’s response was not recorded. But Durham and Ali adjusted.

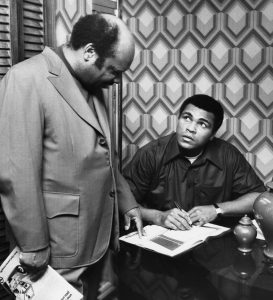

Toni Morrison—once the object of Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael’s) self-admittedly hot-for-teacher crush at Howard, when she was his freshman English professor in the 1960s–joked with Williams in an interview that Ali really adjusted. “Ali was sort of flirtatious, (but) like a boy almost. When I first met him, he said, ‘You know, we can have three wives.’ I said, ‘Please! I’m old enough to be your mama!’… (He was) an absolute delight, and that delightful quality Richard was able to catch.” She found working with Durham “exciting,” because the writer “had a theatrical eye” and knew “what to throw out and what to include…. what was interesting and what was not, and how to make a scene.” Durham was clearly in a powerful social vortex between 1970 and 1975, as Ali slowly moved past racist white terrorism to locally-sanctioned bouts that kept him moving toward the will of Allah, which included the United States Supreme Court conspiring to keep him out of jail, and then George Foreman and Zaire. Durham was on the scene while simultaneously creating it, an insider within one of the greatest final stories of the Black Power 1970s.

But although Durham had the authorized scoop, it was The Nation who called the shots with the book, not he or Morrison. “Durham warned me that there would be some problems with censorship,” Morrison recalled. She accepted that The Nation would have the final say on what was published, but not completely. Ali’s manager, Herbert Muhammad, the son of Nation founder Elijah Muhammad, was “very controlling,” and Morrison had to battle with him—as did Ali!—with what would be in the final manuscript, with Durham as the mediator. Muhammad vetoed any “locker-room language,” she remembered. Ali fought to keep a conversation with his first wife Sonji in the book, an angry exchange that climaxed with her calling him a “World Heavyweight Champion Motherfucker!” Muhammad said no, and Ali and Morrison said yes—but, apparently placating Muhammad, only used the MF initials.

Move the cursor to 1974. Morrison would have great success that year with another of her Random House books, Angela Davis: An Autobiography. But Ali’s was still getting its gloves on. Durham was writing on the run. Morrison was annoyed, but she said “everything he actually delivered was so good. So he would keep me at arm’s length when he didn’t have it or didn’t want to turn it in…. for whatever reasons.” Having a front-row seat to Ali’s Africa summit, Durham finally turned it in after the Return of the King, and The Greatest: My Own Story was published in 1975.

Morrison talked to Ali biographer David Remnick about how Ali deliberately attempted to undermine his own book when it was released. Back on the throne, Ali claimed correctly that he hadn’t thrown away his 1960 Olympic gold medal in a fit of rage against white supremacy, as was written by Ali-Durham. He also said he hadn’t read a word of the book. So, as seen by Morrison, Ali “discredited the book in a way that was unfair to the stories he had told Richard in the first place, or to the stories Richard may have invented to make a point.” Williams wrote that the book ultimately was a victim of Random House’s deadlines, the editorial choices of Durham and Ali, and The Nation’s censorship. However, the Hollywood film rights were optioned, and that’s how The Greatest, the Black response to Rocky (and of course, that film’s loudmouth loser-turned-buddy Apollo Creed), came to theatres in 1977.

All the players moved forward in one way or another. Durham faded into obscurity, but with a pile of money that came from the Greatest film option. Ali continued his proto-slam-poetry career, interrupted occasionally by heavyweight championship boxing matches and being interviewed by Howard Cosell for ABC’s Wide World of Sports. As he prepared for Foreman, Ali spit:

I’ve wrestled with alligators, I’ve tussled with a whale.

I done handcuffed lightning and thrown thunder in jail.

You know I’m bad. Just last week, I murdered a rock,

Injured a stone, hospitalized a brick.

I’m so mean, I make medicine sick.

Oh, yeah, Ali did beat Superman’s ass in the ring, in front of the entire universe. GOAT, indeed. The Nation had to approve that move too, by the way.

Meanwhile, Morrison had more than established herself with Sula and Song of Solomon. In 1983, the original Nation had evolved into the World Community of al-Islam in the West while a new Nation had been rebuilt quietly within Black America’s shadows. Ali had been punched out of boxing and began to see himself as a world humanitarian. But that year is important, because Morrison had floated away from Random House, soaring to the very top of American letters. It was where she stayed until Monday night.

-30-

Todd Steven Burroughs, Ph.D., is an independent researcher and writer based in Newark, N.J. He is the author of Warrior Princess: A People’s Biography of Ida B. Wells, and Marvel’s Black Panther: A Comic Book Biography, From Stan Lee to Ta-Nehisi Coates, both published by Diasporic Africa Press. His 2014 audiobook, Son-Shine On Cracked Sidewalks, deals with the first mayoral election of Ras Baraka, the son of the late activist and writer Amiri Baraka, in Newark. He is working on a journalistic/literary biography of Abu-Jamal.

Now that’s storytelling. Excellent article. Toni Morrison knee who she was and never bowed down to anyone. Her legacy lives on… Rest in Power Ms. Morrison!

A true testament has joined the ancestors! It’s important our descendants of this earth now her legacy! I just saw a movie about her this past Saturday in NYC! SIP MaMa Morrison

Bring back the 60th… Dick Durham, Muhammad Specks, the Office On 79thSt. … right down from the Tiger Lounge!Chicago! Bill Quinn!

“The kind of beauty I want is the hard to get kind, that comes from within- strength, courage, dignity”: Ruby Dee; actress, poet, playwright, journalist, civil rights activist.

“I don’t like boxing, but his grace was almost appalling”: Toni Morrison.

Ali’s grace, outrageous indeed, so shocking that he turned boxing into an art form, making a ballet out of brutality!