Black Power, Black Lawyer: My Audacious Quest For Justice.

Nkechi Taifa. Foreword by Greg Carr.

Washington, D.C.: House of Songhay II., 379 pp.

Reviewed by Todd Steven Burroughs

Back in the days when radicalism was the norm in Black America and elsewhere, there once was a girl who sat on a Black Panther’s lap, abandoned her slave name for Nkechi and discovered a church that taught that Jesus was an African with multiple wives. She also found a home, within and without, as a citizen for a new nation—the Republic of New Afrika, a land whose boundaries only existed within the Black radical imagination. Later, she attempted to cross over in the L.A. Law ‘80s, but the People’s Movement wouldn’t let her go. She defended white radical bombers and Black young people caught up in the system for stupid, racist reasons. She found and lost love more than once, made some loot, demanded reparations way before it was popular and prayed to African gods to search among the Realm of the Unborn for a child, one they eventually gave. She aged but did not grow out of fighting, because she would never forget those behind the bars fashioned out of the white hegemonic marble of the Constitution she had to wear with her ever-present African headwrap.

Whew! If that sounds like a lot for one memoir, that’s because it is. Nkechi Taifa takes us almost through her entire 65 years, and the ride is filled with accidents, opportunities and struggle both radical and progressive, visionary and incremental. It is an ever-morphing space that flips back and forth between the ancestral plane and the policy brief.

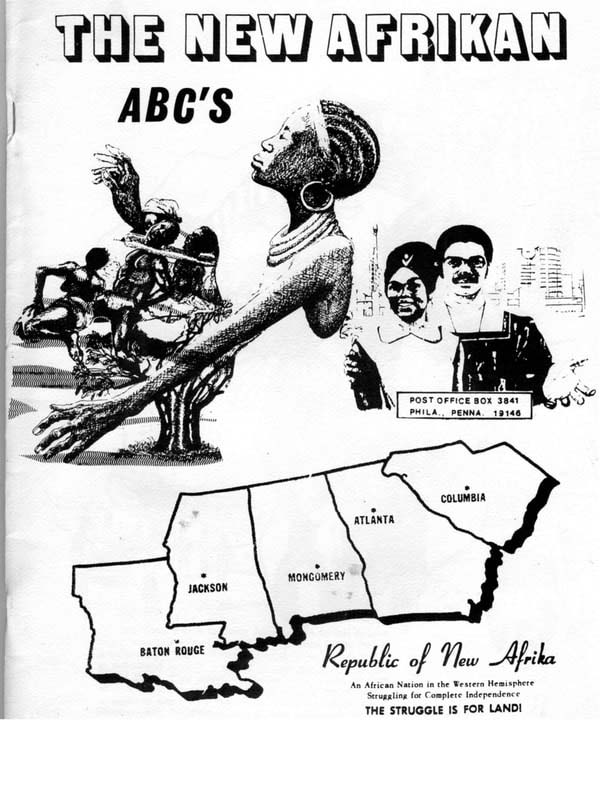

She acts out the collective Zeitgeist. Speak, Drum! Tell the real story! We search for The Main Ingredient among so many. Secretary to a radical publication, the way pre-Raisin Lorraine Hansberry did with Paul Robeson’s Freedom? Check. Sexually abused by a white man she didn’t trust and Black men she did? Check. Radicalized by the Black Panthers as a teenager, a la Wes Cook (Mumia Abu-Jamal)? Check. Going to Howard University, hanging out in a D.C. Black bookstore and attending Black radical political education classes? Yep. Writing and performing radical poetry and plays, a la “Niggers are Scared of Revolution?” Right On! Organizing on the outside for a brother in prison, a la Angela Davis? Check. Stop making up checklists and pick up the gun? Clack-clack. (The Republic of New Afrika’s “political analysis was markedly distinct and abundantly more ambitious than the predominate nebulous calls for a vague Black nation,” writes Taifa, “and represented the next logical phase to the evolution of Malcolm’s thought—identification of a specific land base,” Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina and Louisiana—“buttressed by international law, and protected through self-defense.”) Becoming a lawyer because the Movement needed it, like Marian Wright (Edelman)? Si. Moving on and joining the progressive wing of the system? Step.

The Black Radical Boomer story never gets old. What’s fascinating in this instance is that she does all of this on her own Black radical terms, from yesterday to today. What is supposed to be insider/outsider tension is just transitioning back and forth. The power of being a Washington, D.C. lawyer who was not afraid to be poor, not afraid to not be on the white guest list, ironically, put her in opposite situations, with an upscale house and access to the Obama White House to successfully lobby for crack/cocaine disparity commutations. The only people who know the real her, she reminds herself and the reader, are the authorities, who restrict her West Wing access and stop her at an airport.

Unfortunately for the casual reader, this book cannot decide whether it wants to be a Black radical memoir with one shifting narrative or a string of sista-gurl-I’m-just-like-you semi-chronological vignettes of real-world, real-life situations. It desperately needs a revised edition and a ghostwriter so that it approaches its potential: the time-spinning, thematic power of an Assata or Angela autobiography. (So much ancillary material, for example, that should be in an Appendices is in the main text, dragging out the narrative.) But for those willing the plow through it, it contains just enough of the three h’s—humor, humility and happiness—to make the reader want to continue.

This book has been decades in the making because it is an act of massive remembering; the altar she brings is huge and contains multitudes. So before Taifa returns to where the wind began, she has made sure to document—to call up into being and freeze them in mid-action—those Ancestors who never made The New York Times and Washington Post obit pages: decolonized New Africans (and some whites) who were so serious about revolution they have been placed permanently outside of polite Black memory, exiled into near historical and mental non-existence.

Throughout, Taifa is trying to articulate what she innately knows—and ultimately winds up saying without saying: that love for one’s own is more consistent and creates more momentum than rage against The Man, that work is more important than critique, that organizing within organizations beats mobilizing every time, that disappointment is inevitable but always temporary, and that time itself is globular, nonlinear, so the key is to be encircled within it.

-30-

Todd Steven Burroughs, Ph.D., is an independent researcher and writer based in Newark, N.J. He recently completed a draft of Talking Drums and Raised Fists: Mumia Abu-Jamal, A Biography of a Voice and is working on a second Abu-Jamal book, a biographical anthology. He is the author of Warrior Princess: A People’s Biography of Ida B. Wells, and Marvel’s Black Panther: A Comic Book Biography, From Stan Lee to Ta-Nehisi Coates, both published by Diasporic Africa Press. His 2014 audiobook, Son-Shine On Cracked Sidewalks, deals with the first mayoral election of Ras Baraka, the son of the late activist and writer Amiri Baraka, in Newark.