“U.S. of A. / U. of S.A.” – Art Ensemble Of Chicago / With Amabutho – Art Ensemble Of Soweto

“He’s out to neutralize, not to awaken.” – Willa Paskin

It was thought a good idea by the leadership of the School of Global Journalism and Communication at Morgan State University to encourage professors, like myself, teaching in that school to find ways during the Fall semester of 2017 to incorporate into our work the then new book Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood by Trevor Noah. Noah is the South African-born, biracial, Colored comedian and host of Comedy Central’s The Daily Show. Copies of his book were distributed to students and faculty alike and there was an eventual trip arranged for some to visit a live taping of the show. I was not invited.

Immediately my classes and I can start with critiques of false balance and Western politicized notions of objectivity both of which were in play during Noah’s recent extended exchange with the equally (more so?) popular aggressive right-wing Tomi Lahren. Many know of Noah’s nightly television work and it appears many more know him now after the straw woman performed her role in enhancing Noah’s credibility and right in time to coincide nicely with his book’s launch. What liberal aspirant to the throne of legitimacy wouldn’t want her as an interlocutor? Even in the silly film Pop Star Conner Friel (Andy Samberg) made sure his entourage consisted of a “perspective adjuster” whose sole function was to make the star look better by comparison. Muhammad Ali’s legend wasn’t born by his fights with Henry Cooper and Brian London. It were those fights with Liston, Frazier, Foreman and the federal government that told us he was the greatest.

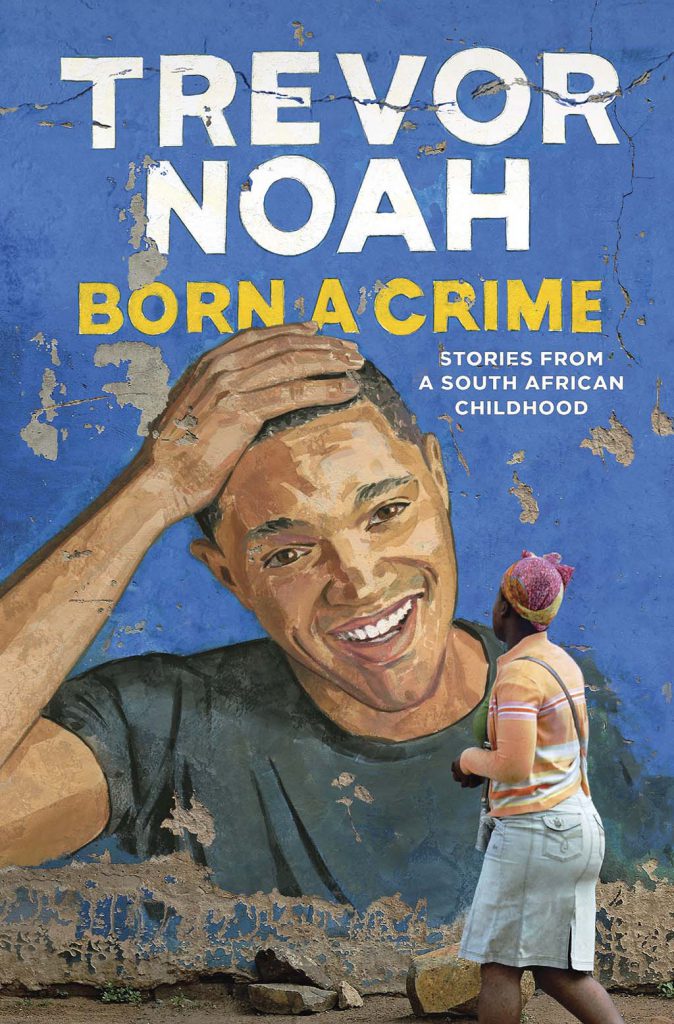

We can also as a class ask, what is happening semiotically with the book’s cover? It read to me from the first like the perfect singular symbolic display of Noah’s entire political function as celebrity, the quintessential image encapsulating all I had seen of him previously and his particular brand of bi-racial, Colored performance. Noah’s beige face, askew, askance even – especially – with that grin, hand touching his head, painted on a tattered township wall, imposing, top-down upon a faceless Black African woman, almost saying, in an aloof, twisted version of the Old Spice commercial, “aww-shucks, look at me. Now look at you. Now look at me again. Now look at you. And back to me. I’ve made it and you can to? Never mind that. Look at me!” Its reminiscent of any billboard falsely advertising an exclusive lifestyle of which most onlookers can only dream.

Again, before even opening the book. What is being conveyed by the title itself? Born a Crime. Its certainly provocative. The tendency will be encouraged to read this as Noah emphasizing the insanity of apartheid and its racial codes. But, particularly when considered next to the content and approach of the book itself, the title seems more and more to me to be about claiming a legitimacy that works to protect against critique. Yes, Noah was indeed born a crime by the laws written in South Africa against miscegenation. But the phrase is used here almost as a bludgeon that seeks to elevate Noah to a position of authority, authenticating approaches to covered topics that reaffirm norms rather than challenge or threaten them. Remember how Charlamagne practically gushed over Noah’s racial experience and expertise on The Breakfast Club? As if Charlamagne doesn’t come from a country settled by invading Europeans at the expense of genocide, forced removal and enslavement which created still-existing racial categories, boundaries and unequal (and devolving) material lived experiences. In fact, the U.S. is headed for White minority rule which already exists in U.S. media ownership which has led to it being referred to already as an apartheid media system. But where some comparative analysis might be of value Noah’s work reads as an attempt to create distinction for the sake of enhancing his or his brand’s value. Branding, another great topic for class! Marshall McLuhan did once describe advertising as a “military operation.”

And then to the book itself. Born A Crime is a personal memoir that isn’t particularly riveting or complicated or deeply analytical regarding the history and lingering effects of apartheid, here I am comparing it negatively to Frank Wilderson’s far more powerful, investigative and damning Incognegro: A Memoir of Exile and Apartheid. Among the many differences, however, is the distinction that Noah’s is not a movement biography. Noah was barely six when Nelson Mandela was released from prison and he apparently fully adopts uncritically the dominant narrative that this signified an end to apartheid as opposed to that of armed struggle, the leadership of Chris Hani or the Freedom Charter.

The chapters consisting of Noah’s selected stories open with short historical overviews, quick highlights of apartheid and light backgrounding. Not so much substance, nothing drawn from a perspective of (radical) political struggle, so its just enough to draw a reader into gentle renditions of a nightmare. This is, after all, a top five publisher’s product, Random House is looking for big distribution numbers and best seller’s lists, the kind that requires a particularly broad approach that will attract White affluence and praise. Noah’s book is obviously and understandably meant to supplement, not scuttle, his day job of hosting a nightly commercial television show catering primarily to those same younger, Whiter, more affluent and liberal audiences. They will tolerate and even enjoy Noah’s stories about apartheid because rather than remind of a dark (pun intended) past Noah speaks mostly to the brightness (again, pun intended) of a post-apartheid future. Never mind how that is working out either by the way. Look at me!

We get vignettes of Noah’s experience as a “mixed-race” Colored. Little of Noah’s White father whose disappearance feels almost like an out for White readers forced to face something about the racial violence of apartheid. After the initial description of a broader system White involvement is less emphasized, replaced with the more comforting focus on Black male pathology – via Abel, Noah’s stepfather. There is also the interesting but yet still comforting and focus on Noah’s Black African mother – specifically her Christianity presented of course as an unquestioned positive with nothing really suggesting it too results from Western imperialism and violence.

In fact, perhaps our class can look at this issue critically, how violence is welcomed in the mainstream to the extent that it is intra-communal, never directed at power. This is part of the recipe for success in the U.S. for sure where White producers, directors, and writers of Black pathology receive McArthur Genius Awards and Oscars. Violence in Noah’s book is mostly relegated to incidents among the Black or Colored majorities and since the memoir avoids apartheid’s political struggles as a subject we don’t read of violence in the context of revolutionary armed struggle (in which Mandela had himself been involved) – the Umkhonto we Sizwe, MK or “Spear of the Nation” – nor do we read of violence meted out by the state upon fallen heroes like Hani, Steve Biko, or now the late Winnie Mandela.

Mirroring the approach in Born a Crime is Noah’s recently published New York Times opinion piece in which he more or less uses the authority given him by his pop-celebrity – which is the real political function of fame (classwork!) – to create South African apartheid as the authenticating backdrop to his own very liberal and sophomoric approaches to problems of race and class. This authority allows him to use the preferred narrative of South African history and Mandela’s release to tell us here in the U.S. that “moderation and compromise” are not “selling-out.” But then what does this say to the radical traditions left unmentioned by Noah, traditions still alive in the work of the Economic Freedom Fighters or Black Land First movements? Never mind that. Aww shucks, look at me!

And here, as former political prisoners like Dhoruba bin-Wahad call for radical responses to a creeping fascism, what do more popular counter-narratives mean? In fact, Noah’s advice from Born a Crime is that we get over a past and a set of processes set in motion during enslavement, apartheid, colonialism, Jim/Jane Crow, etc. that neither he nor anyone else can offer evidence has abated. Given recent economic studies, it would seem the opposite is true. But never mind that, as Noah says, “move on.”

If you think too much about the ass-kicking your mom gave you, or the ass-kicking that life gave you, you’ll stop pushing the boundaries and breaking the rules. It’s better to take it, spend some time crying, then wake up the next day and move on.

This all will be great for in-class discussions of Stuart Hall’s dominant, oppositional or negotiated narrative readings!

Perhaps our class can ask that question and attempt to find its answer in Noam Chomsky and Ed Herman’s Propaganda Model critiquing elite media bias. For instance, both the New York Times and The Guardian published their praise for Noah’s book and I wonder if it helped that Times’ readers, for instance, won’t find much in Noah’s memoir reminding them of the long history of U.S. support for that country’s White minority regime or how their Black Consciousness Movement reflected and inspired alike the Black Power Movement here. Nothing from Noah will remind them that the U.S. could have learned plenty prior to ’08 about the failure of Black leadership imposed on largely unchanged structures culminating in actual declines in the material livelihood of Black people. Nor will the Guardian’s readers be reminded much of England’s role in conquering and then maintaining colonial and apartheid rule for centuries.

Where Noah almost threatens himself is in his nearly powerful assertion that for Africans imperial invaders like Cecil Rhodes and King Leopold are considered worse than Adolph Hitler. This is a dangerous thread which cannot be followed to its logical conclusion in mainstream commercial media. He has to leave this short and couched in a story about a childhood friend because to do so, to follow this logic, would mean concluding that the West itself, the acceptable West – not just the outcast Nazis of a German “past” – is in opposition to African liberation and sovereignty.

Then there is this interesting interplay carried on by Noah in his performance of identity, being African, yet both bi-racial and Colored and yet also acceptably Black in the context of the U.S. Noah, a child of a Black African Xhosa woman and a White Swiss father, is largely read as Black in a North American context, and so is legitimate enough to perform his role as a distiller of race for Whites while persisting their established ideologies around race (White superiority, Black inferiority, etc.). Whereas we who are “mixed” – particularly those of us comprised of Black/White – can potentially explode White supremacist notions of race by having our experiences inform a radical critique of the hostile relationship between our parent communities or by challenging concepts of racial categorization itself Noah’s approach, exemplified in Born a Crime, is better understood in the context described by Ralina Joseph as a “boom” in “Mixed-race memoirs [which] are a recent phenomena produced for and by the Loving generation, the population of multiracial people born after the 1967 Supreme Court decision legalizing interracial marriage, Loving v. the State of Virginia…” A movement which emerged largely “[s]ince the early 1990s with the birth of an active ‘Multiracial Movement’ and a flourishing of scholarship on multiraciality…” And, as Joseph and Jared Sexton, among others, have explained, this “Multiracial Movement” in the U.S. is one largely created and led by White women whose children by Black men they did not want to be so directly connected to Black communities, struggles and histories. That these women also represent a core segment of Noah’s and Comedy Central’s target audience might also suggest why his particular approach works.

Noah attempts to craft a very distinct and authoritative (multi)racial personae, one perfectly suited to his position as an elite commercial media product, one that allows him to be seen enough by American commercial media audiences as an authority on race largely which he appears to be precisely because of his particular brand of anti-Black racial ideology reaffirmation. It works because he is, but yet isn’t, Black. It’s a kind of “connected distance” that helps authenticate while mollifying. He is special but not so much as to really challenge convention. As has already been noted by Tomi Obaro, Noah’s rise to prominence in the U.S. coincided with his routine willingness to use appearances in this country to denigrate Black people:

“That special wasn’t even the first time Noah has made jokes at black Americans’ expense. When he was tapped as the first African comedian to ever perform on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno in 2012, he used the historic moment as an opportunity to marvel with melodramatic wonder at black American names: “It’s almost like they lose their minds with the Scrabble pieces while giving birth.” The jokes were embarrassing enough that, three years later in a 2015 GQ interview, Noah apologized (kind of): “I hadn’t fully understood the African-American experience. I hadn’t read the books; I hadn’t met the people; I hadn’t traveled the country,” he assured writer Zach Baron.

It is so interesting then to read in Born a Crime of how Noah’s Black African mother named him Trevor, “a name with no meaning whatsoever in South Africa, no precedent in my family. It’s not even a Biblical name. It’s just a name. My mother wanted a child beholden to no fate. She wanted me to be free to go anywhere, do anything, be anyone.” “Beholden to no fate” can just as easily be read as “committed to no struggle, no politics, no people” with the freedom to go anywhere, assume any role, be, as Noah has also said, “anyone,” a “chameleon.”

In some ways this liminality by naming reads, which is consistent with the prevailing content of Noah’s performance that often feels fluid and searching, like the young man who applied his multilingualism as self-defense to where “…it became a tool that served me my whole life… I became a chameleon. My color didn’t change but I could change your perception of my color.” Fascinating, even impressive. But this shape-shifting self-defense for survival in the streets or to find success in commercial media is not nearly as original as Noah seems to want us to believe – or needs us to to create that sense of distinction and authority. However, perception management – a core concept for our classes! – is an essential component to public relations (read: psychological warfare, propaganda, advertising, marketing).

I look forward to this semester’s forthcoming school-wide readings of Noah’s book. As bell hooks has said for years, there is real value in popular media/cultural product being brought into the classroom served up as aids in the development of critical thinking and the creation of ourselves, as she said, as “enlightened witnesses” to media. I’m excited, so in the immortal words of Pharoahe Monch, “Let’s Go!”

A ‘Fat Chance’ Dream

Comedian,Trevor Noah becomes fully aware of fellow countryman, the late great South African freedom fighter, Steve Biko, and has his ideology completely revamped. Biko’s understanding of Black Consciousness as a weapon of change could not be more relevant today to help restore Mr. Noah to his full humanity:

“What Black Consciousness seeks to do is to produce real black people who do not regard themselves as appendages to white society. We do not need to apologize for this because it is true that the white systems have produced through the world a number of people who are not aware that they too are people”.–Steve Biko: The Definition of Black Consciousness; I Write What I Like, 1978.